Published by 1. Nuri Berisha, 2. Bahri Prebreza*, 3. Petrit Emini, Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, University of Prishtina

ORCID: 1. 0000-0001-8615-637X; 2. 0000-0003-1950-026X; 3. 0000-0002-2833-9001

Abstract. Power system harmonics have a significant impact on the efficiency, reliability, and stability of the system. Low power quality is determined by undervoltages and overvoltages, dips and swells, blackouts, harmonic distortions, and transients, among other phenomena. ETAP is used to illustrate the specific examples related to these deviations, and the results are graphically displayed. The real induction motor and substation 110/35kV Gjakova 1 within the Kosovo Power System are analysed as a case study. Voltage deviations, load flow, and voltage changes before and after power transformers are analysed.

Streszczenie. Harmoniczne systemu elektroenergetycznego mają istotny wpływ na sprawność, niezawodność i stabilność systemu. Niska jakość energii jest określana między innymi przez podnapięcia i przepięcia, spadki i wzrosty napięcia, przerwy w dostawie prądu, zniekształcenia harmoniczne i stany przejściowe. ETAP służy do zilustrowania konkretnych przykładów związanych z tymi odchyleniami, a wyniki są wyświetlane graficznie. Prawdziwy silnik indukcyjny i podstacja 110/35 kV Gjakova 1 w systemie elektroenergetycznym Kosowa są analizowane jako studium przypadku. Analizowane są odchyłki napięcia, przepływ obciążenia i zmiany napięcia przed i za transformatorami mocy. (Analiza jakości zasilania. Studium przypadku dla silnika indukcyjnego i podstacji 110/35kV)

Keywords: Power quality, Total harmonic distortion, voltage dips and swells, ETAP.

Słowa kluczowe: Jakość energii, całkowite zniekształcenia harmoniczne, zapady i skoki napięcia, ETAP.

Introduction

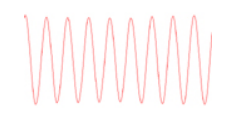

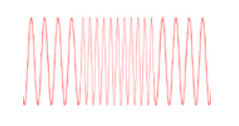

Power quality is an interesting issue used to describe the nonstationary disturbances, which cause the major malfunctioning of electrical equipment. Electricity consumers are becoming more sensitive about power quality issues and in addition, many governments have revised their policies to regulate utilities, and promote the circumstances to improve power quality within defined limits. Modern devices containing microcontrollers and microprocessors are more sensitive to power changes, voltage, and frequency deviations. Overall efficiency in the power system has resulted in increased demand for high efficiency, adjustable motor speeds, and power factor correction to reduce losses. As a result of this development, the increase of harmonics in the electricity system has affected the operation, reliability, and security of power systems. Concerns about power quality are increasing because it has a direct economic impact on supplying factories, equipment, and end users. Transformers, generators, motors, PCs, printers, communications equipment, and other electrical appliances are very sensitive regarding power quality standards. Harmonics are used to mathematically explain the shape of non-sinusoidal voltage and current curves and total harmonic distortion. Total harmonic distortion (THD) is the summation of all harmonic components of the voltage or current waveform compared to the fundamental component of the voltage or current wave [1]. The Fourier series is used to determine the mathematical form for modelling and for calculations. An explanation of how power quality parameters are analysed using ETAP software is given, and it is presented the variation of the total harmonic distortion before and after the power transformers. Variations of voltage, current, and harmonics level are considered very high risk for electronic equipment and are qualified as parameters that characterize an inadequate power supply. Adequate power quality means that the issues such as: under voltages and over voltages, dips (or sags), surges (or swells), blackouts, harmonic distortions, and transients must be improved or brought to the smallest possible values because their complete elimination is impossible. The tendency is to decrease or eliminate these deviations, which means that the quality of the power supply will improve. Also, here are described in detail the deviations, processes, and possibilities of how the linear voltage deviations can be eliminated from the sinusoidal shape. Various dynamic processes that can cause the deviations mentioned above are a motor start, commutation, load switching, etc. [1, 2].

Poor power quality is the terminology that describes the deviations of the voltage waveform from its ideal curve shape. According to the IEEE Institute, the IEE 1100 Quality Standard is defined as follows: “The concept of supplying electricity to sensitive electronic devices in a manner suitable for the supply of equipment by the conditions of electrical installations and other equipment connected to the network”. Power quality is described through under voltages or overvoltages, dips (or sags), surges (or swells), blackouts, harmonic distortions, and transients. In this paper, the focus has been more on voltage dips, voltage swells, and total harmonic distortion – THD. Keeping low THD values on a system will ensure proper operation of equipment and a longer equipment life span [1, 2]. The standard claims that harmonics can lead to electrical losses in motor rotors and transformer cores via hysteresis and eddy currents, which causes them to overheat. Torque decrease occurs in motors. Electronic equipment responds erratically to high harmonics.

Power quality analysis

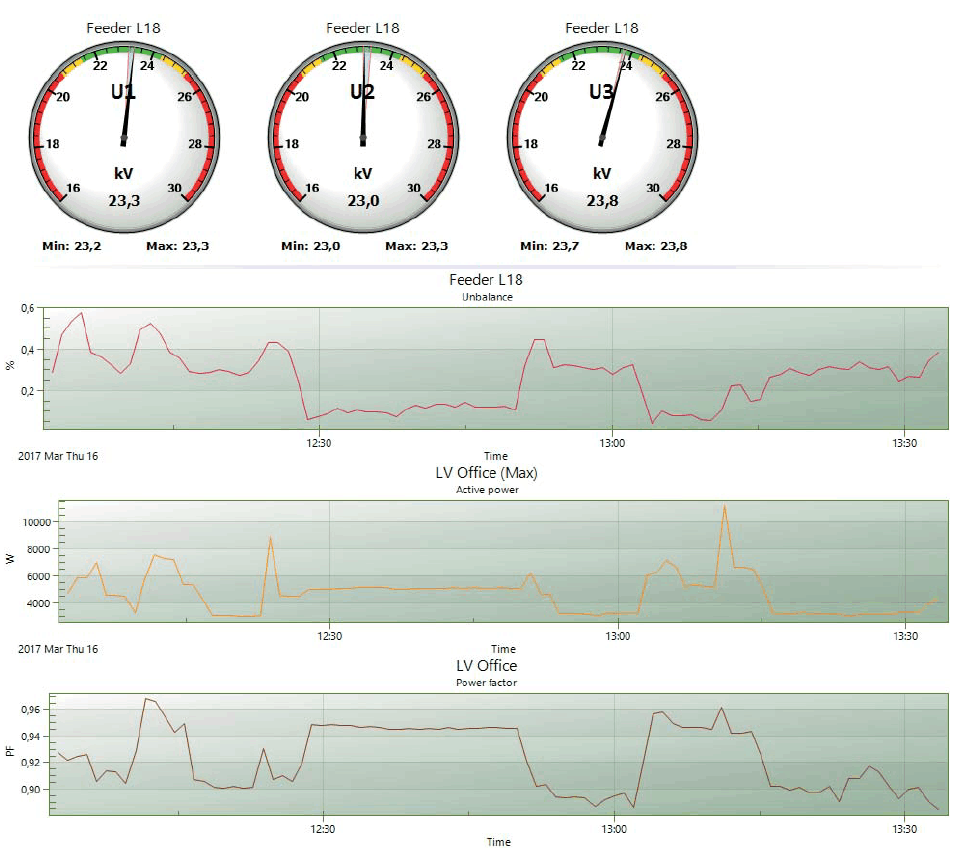

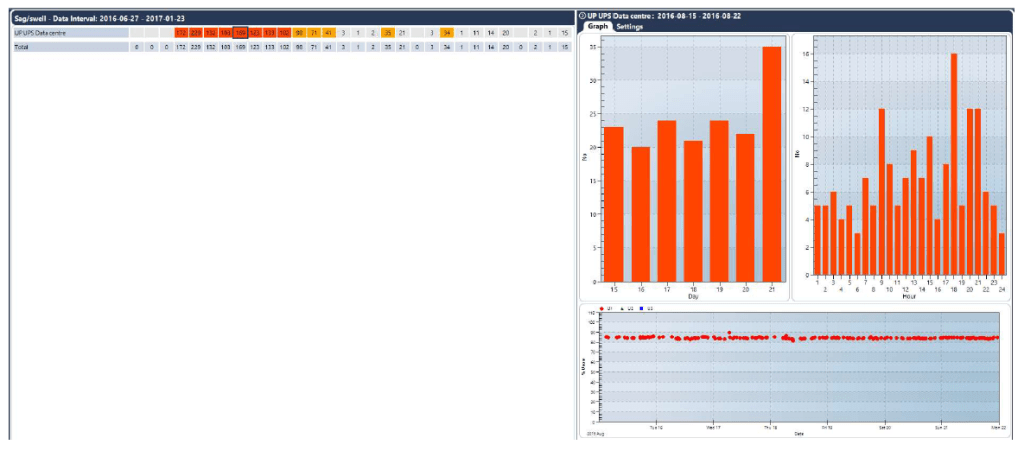

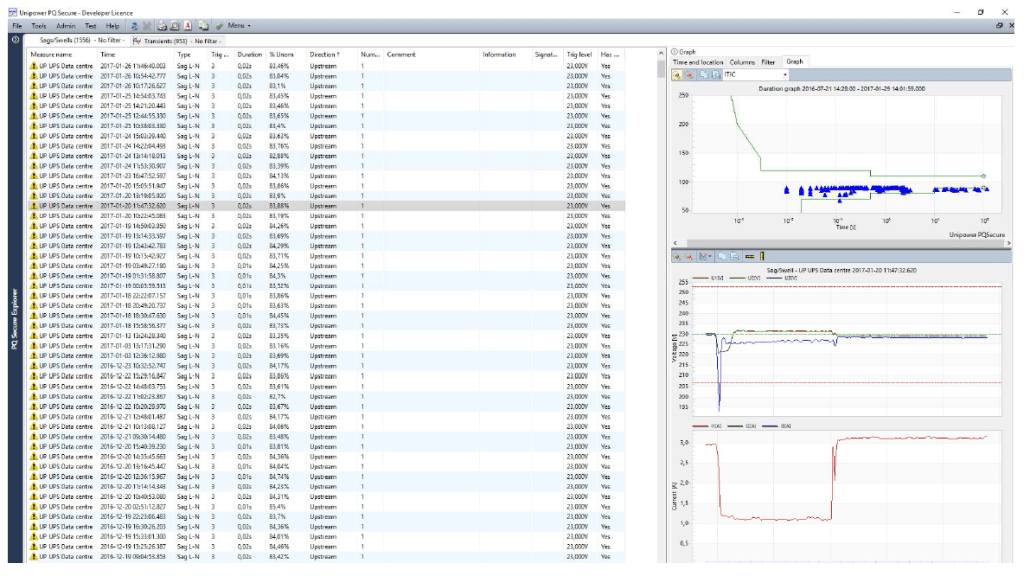

The sinusoidal deviations of the linear voltage, current, and various dynamic processes are described in this section. These processes include motor start, connecting and disconnecting the load at the end of the line, etc. [2]. ETAP is used to illustrate some cases where deviations are presented graphically and in the form of reports. Some practical cases are analysed, modelled, and simulated. Here are presented voltage deviations and load currents in each busbar, voltage dips, voltage swells, and THD before and behind the power transformers and transformer busbars.

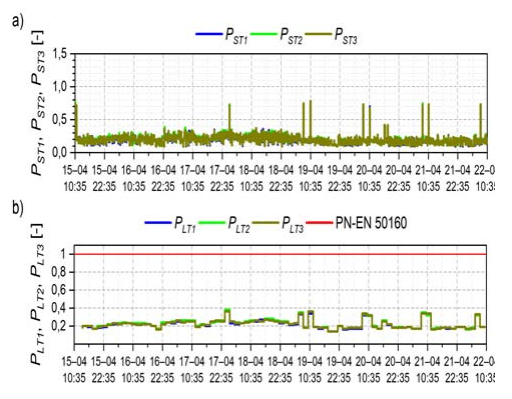

The power grid evaluates power quality using the power quality parameters defined in standards IEC 61000-4-30 and EN 50160 [3, 4]. High frequency switching circuits included in electronic converters cause distortion over the typical 2 kHz harmonic frequency region, shifting it to the 0- 150 kHz range [5]. Harmonic distortions in power systems are affected by the extensive use of modern power electronic-based loads and the significant integration of renewable energy sources with power electronic interfaces. [6, 7].

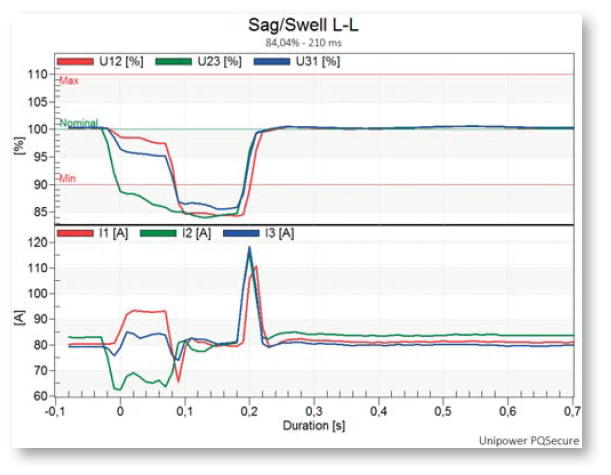

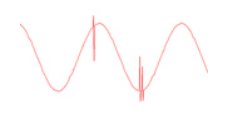

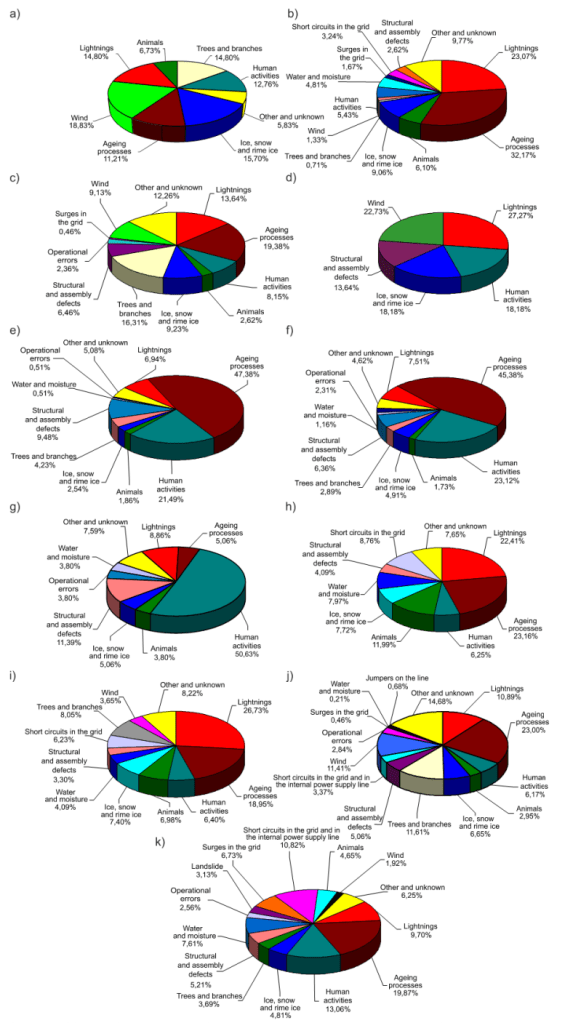

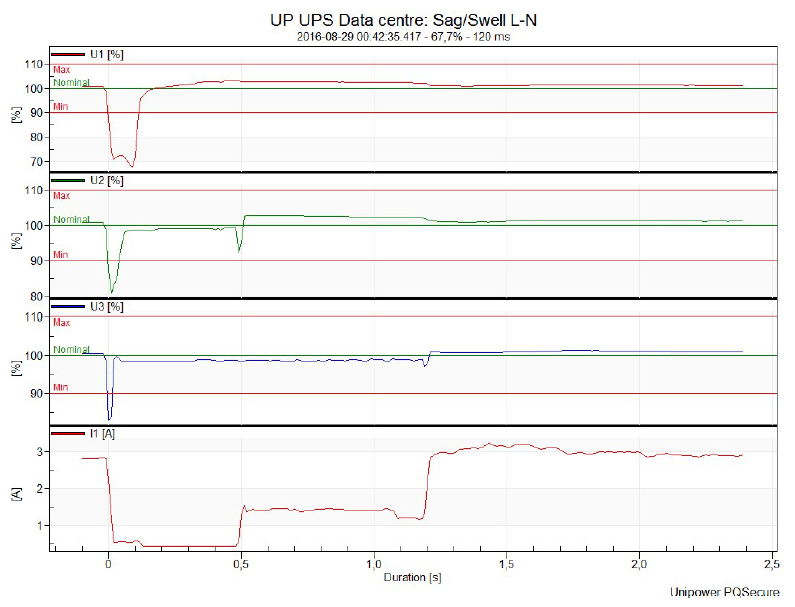

A. Voltage dip is a phenomenon where the effective value of the line voltage is decreased compared to the nominal value of the line voltage, for a short period of time. This type of deflection is caused by overloads at the end of the line, by short circuits in the three-phase motor, or by short circuits in the generator [8, 9].

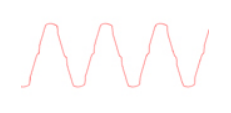

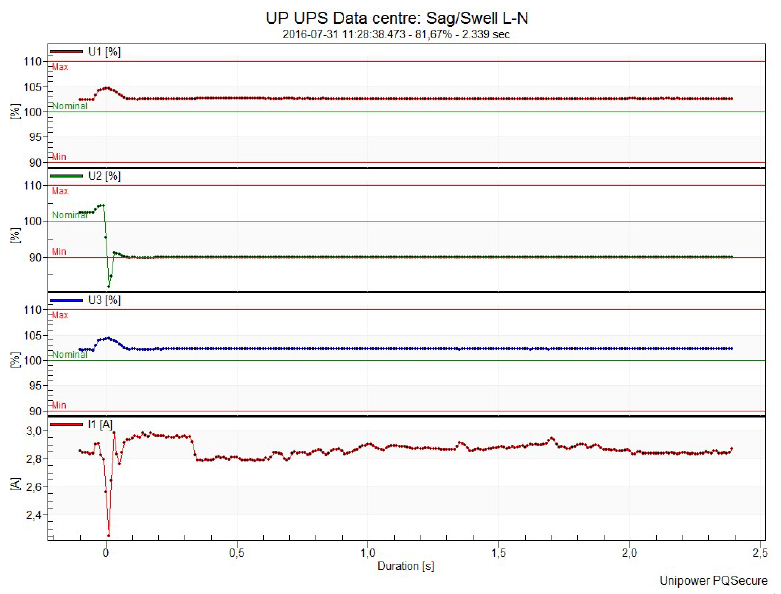

B. Voltage swells are rapid voltage rises over short time intervals. Voltage swells are the opposite of voltage sags (dips), and they are defined in the IEC 61000-4-30 standard as:” a momentary increase in RMS voltage of 10% or more above equipment recommended voltage range for a period of 1/2 cycle to 1 min”. Voltage swell is also defined by IEEE 1159 as:” the increase in the RMS voltage level to 110% – 180% of nominal, at the power frequency for durations of ½ cycle to one (1) minute”. As a phenomenon, it is classified as a short-duration voltage variation phenomenon, which is one of the general categories of power quality problems and voltage swells pose a risk to electrical equipment. It is an important parameter of power quality. The main sources for the occurrence of this phenomenon are single-phase short circuits to the ground, various switching processes, such as switching on and off large electrical loads, etc [10, 11].

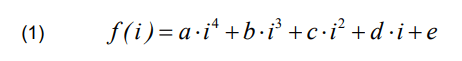

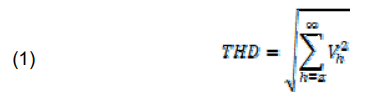

C. Total Harmonic Distortion – THD is the mathematical way of presenting the non-sinusoidal shape of the voltage or current curves. THD can be calculated for either current or voltage but is most often used to describe voltage harmonic distortion. THD can be measured for an existing system or calculated for a proposed system [12]. This mathematical form is calculated using the Fury series:

where: THD – Total Harmonic Distortion, Vh – RMS value of the z-order harmonic.

The waveform analysis for the three-phase rectifier using the Fury series shows a low level of harmonics, except for the harmonics 5, 7, 11, 13, etc. The magnitude of the harmonics decreases with the increase in the order of the harmonics. ETAP is very practical and functional software for power flow analysis, short circuit currents, power quality parameters, motor starting, and various dynamic analyses in electric power systems. A fundamental indicator to evaluate the quality of power systems is the total harmonic distortion. THD is a signal deviation measurement that can be applied to voltages and currents. The interaction of customers’ nonlinear load across the impedance network can affect the supply voltage in electrical power networks [13, 14].

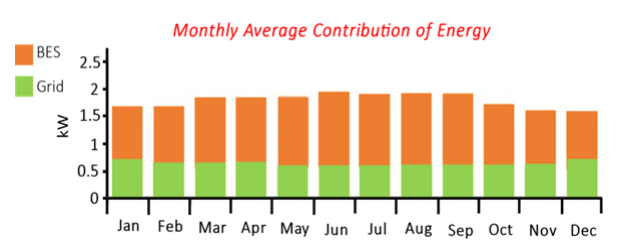

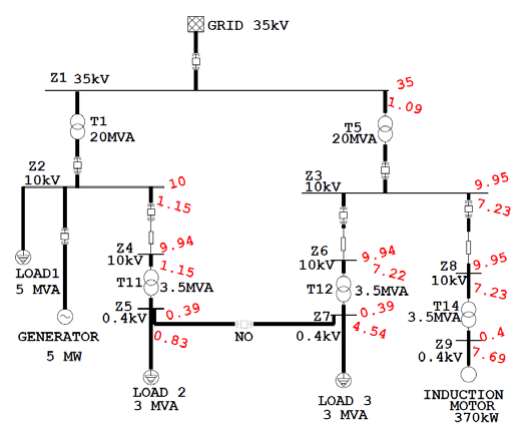

Induction motor simulation studies

Typically, while determining the source of electromagnetic force in induction motors, the impact of fundamental sinusoidal current is mostly considered. The effects of supply harmonics on the induction motor are closely related to its operation, control, and monitoring [15, 16]. Certain attempts are being made to improve the performance of induction motors in many ways, such as increasing their efficiency to meet current energy-saving requirements and objectives, as well as lowering noise and vibrations. [17, 18]. A power system presented in Fig.1. is taken for the analysis. In this case, a 35kV power network with two power transformers 35/10kV (20 MVA), three power transformers 10/0.4kV (3.5MVA), one generator 5MW, power loads 3x 3MVA and one induction motor 370kW, are analysed in this case study.

A. Normal operation of induction motor simulations and results

An induction motor’s air gap magnetic potential will have a variety of rich harmonics present during normal operation due to the cogging of the motor and its windings distributions [19]. The induction motor’s air gap magnetic field has a significant portion of the fundamental wave component under the sine winding distribution, and the harmonic loss is reduced [20]. R.M.S currents of Electrical power systems are increased by current harmonics which also decrease the quality of the supply voltage. They can damage equipment and stress the electrical network. They can affect the normal operation of devices and increase operating costs. Parameters that determine power quality are analysed as part of this study. Voltage fluctuations, such as dips and swells, are presented in the analysis below.

The power system in Fig.1 shows high harmonics across busbars and transformers, as well as through cables. Modelling and simulation study is performed with ETAP software. From Fig.1, it is clearly shown that the harmonic level for the 35 kV main busbar is 1.09%.

As expected, the highest level of harmonics will be at the busbar, where the asynchronous motor is connected. Rotating machines are characterized by a high level of harmonics and for this case, the voltage harmonics level is 9.95%.

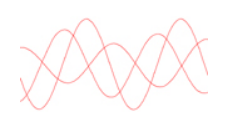

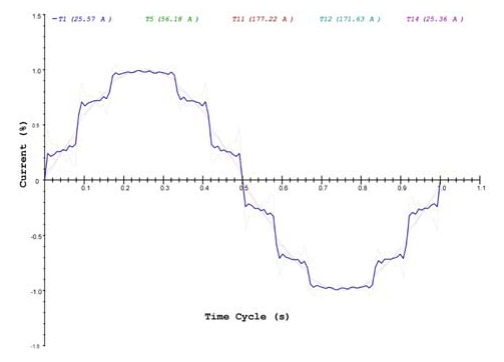

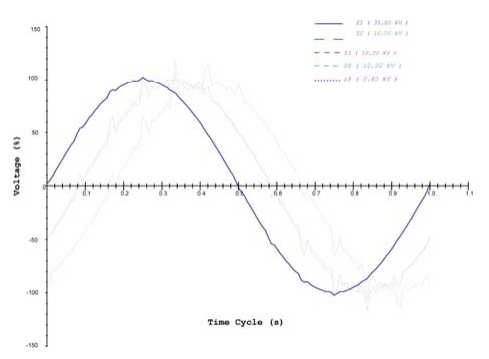

Current waveforms for each transformer are presented in Fig.2. Because an induction motor is connected through the transformer T5, the current THD is significantly greater, because rotating machines create a high level of harmonics. The voltage waveform for each busbar is shown in Fig.3.

Voltage harmonics are also greater on busbars with induction motors, with the highest level (9.95%) occurring on the busbar Z9 where the induction motor is directly connected.

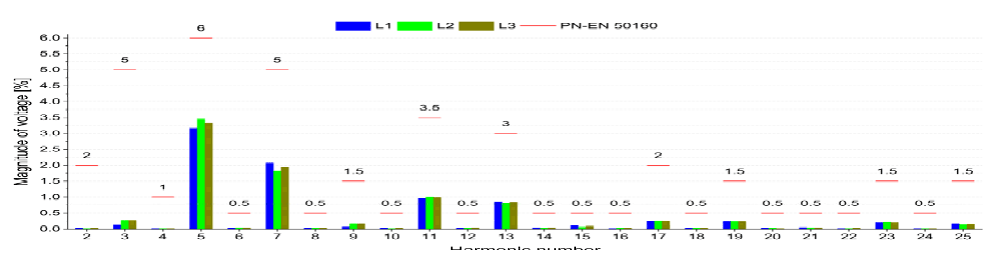

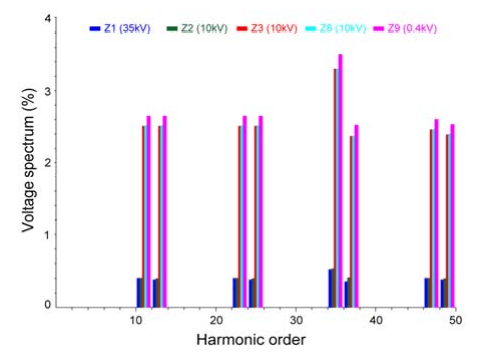

THD spectra (voltage harmonics) are also shown in Fig.4, with the maximum THD seen on busbars Z8 and Z9, and this is because of the contribution that comes from the induction motor connected to the mentioned busbars.

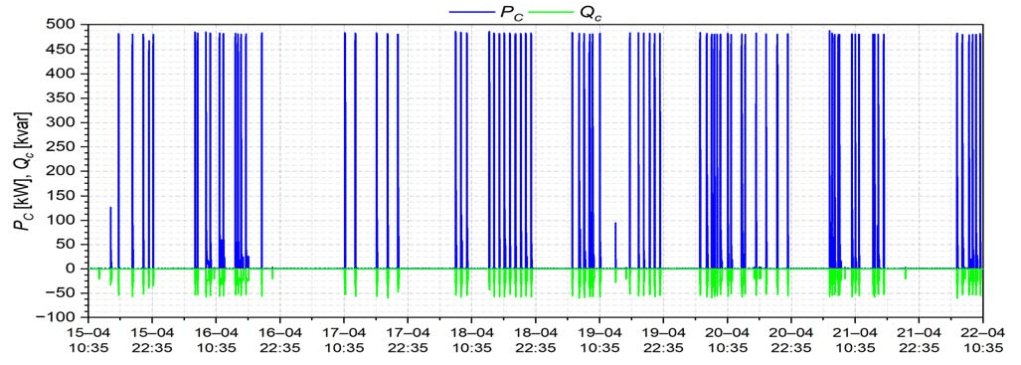

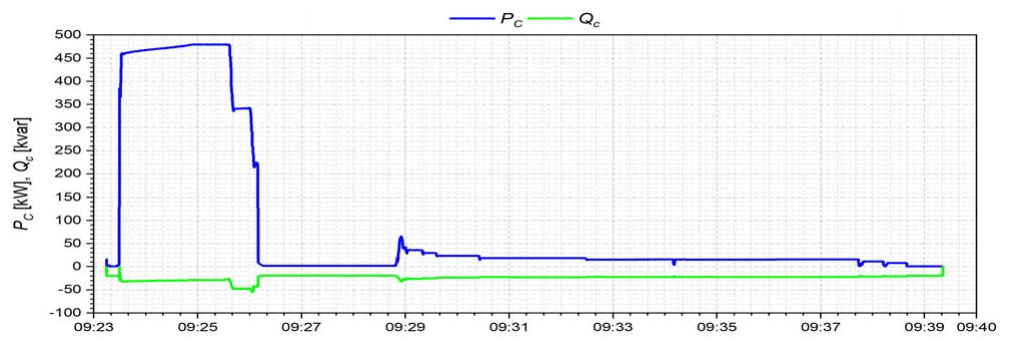

B. Motor starting simulations and results.

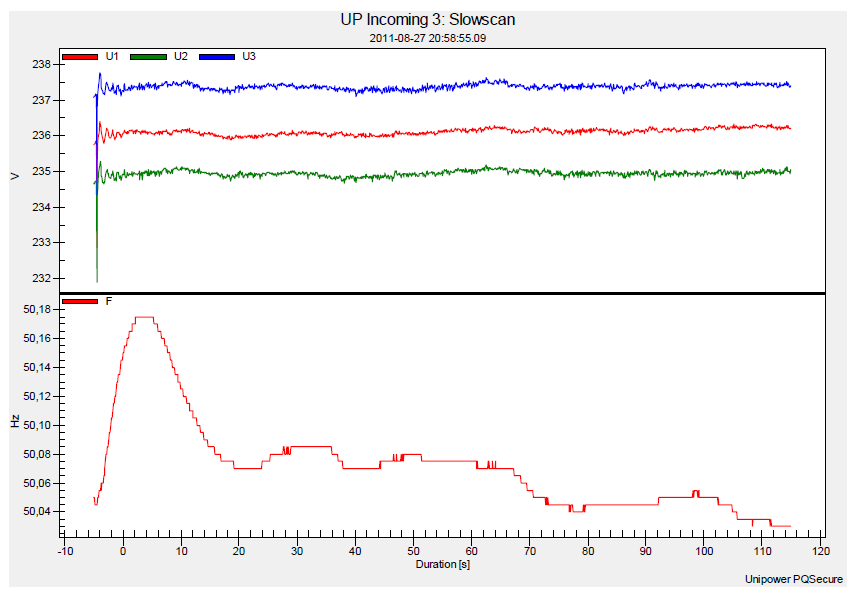

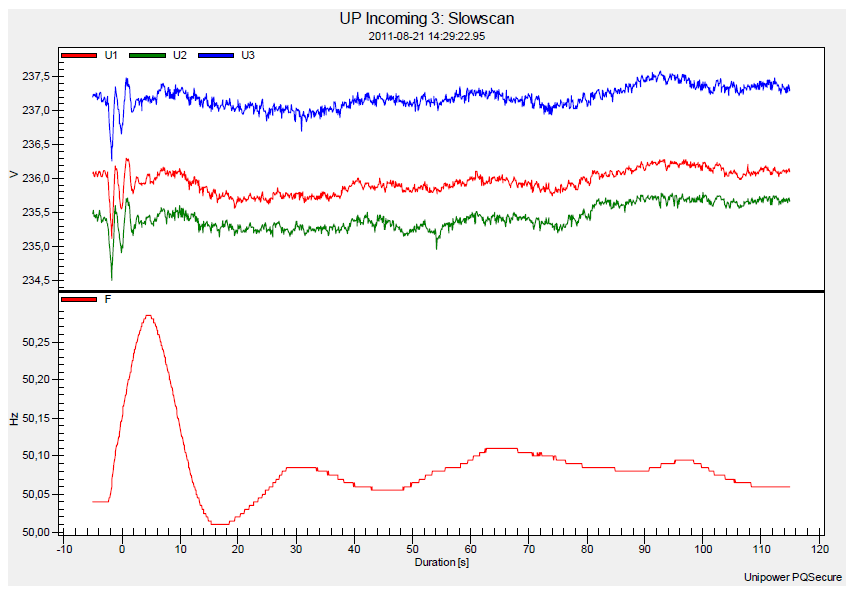

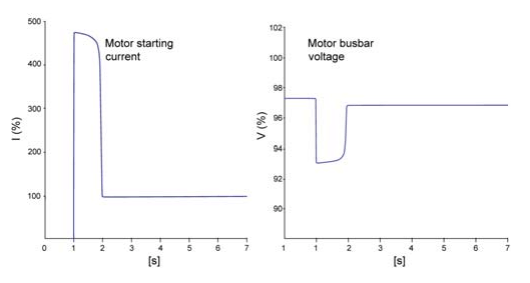

Recent studies on mains-fed induction motors have pointed out the importance of choosing the right number of rotor bars, for example, to decrease Rotor Slot Harmonics (RSHs) and their corresponding parasitic impact under sinusoidal supply [21, 22]. The motor starting is analysed for the same power system as presented in Fig.1. Motor starting is a phenomenon that causes initial voltage dips, but only for short intervals (1s). The current in the induction motor has a value of 2964 A at the time of starting (starting time 1s) [23]. Starting current is nearly four times larger than the nominal current in the motor starting operation mode and on the other hand voltage decreases very fast during this mode. In this case, the voltage drop is to the level of 95%. This phenomenon is known as voltage dip on induction motors, it lasts one second from the starting time (in this case, starting time is in the first second of simulation) and is presented in Fig.5.

Substation Gjakova 1 simulations and results

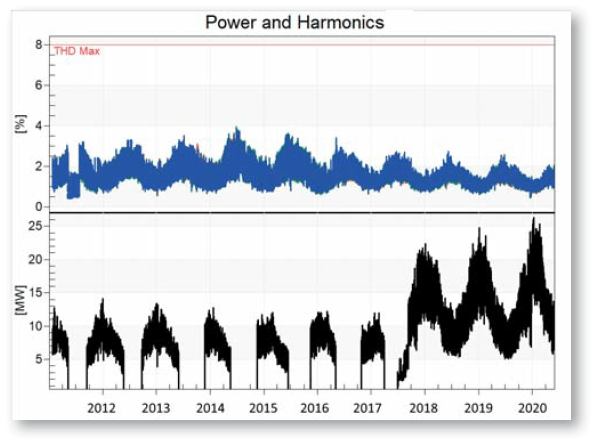

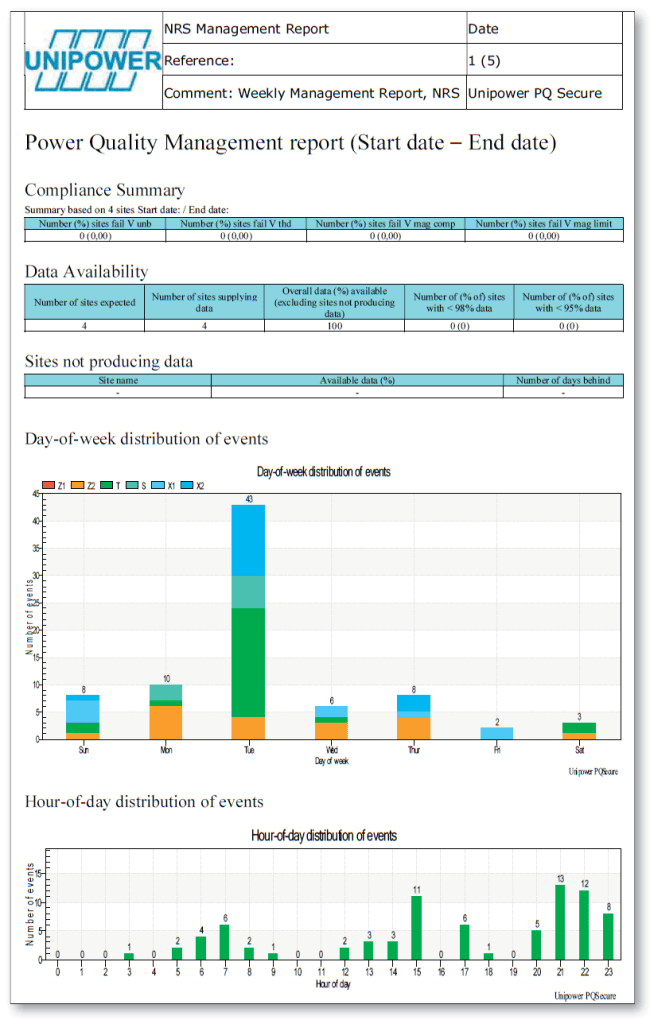

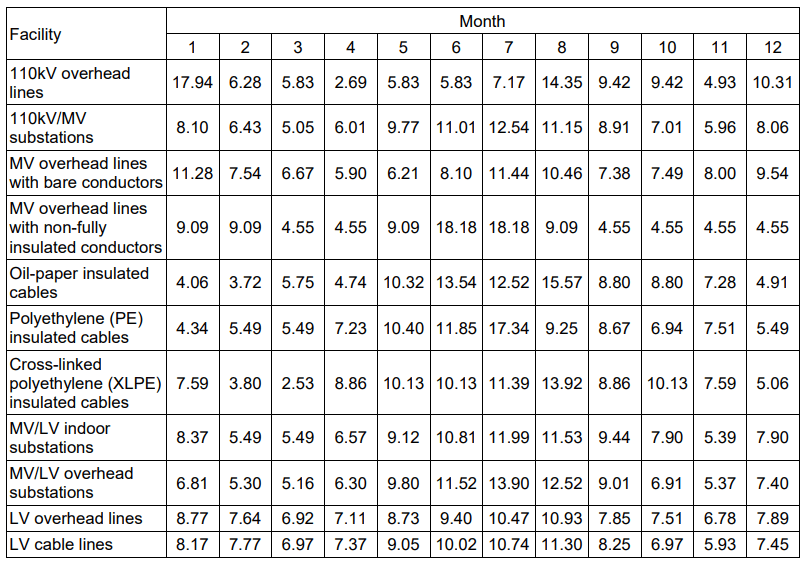

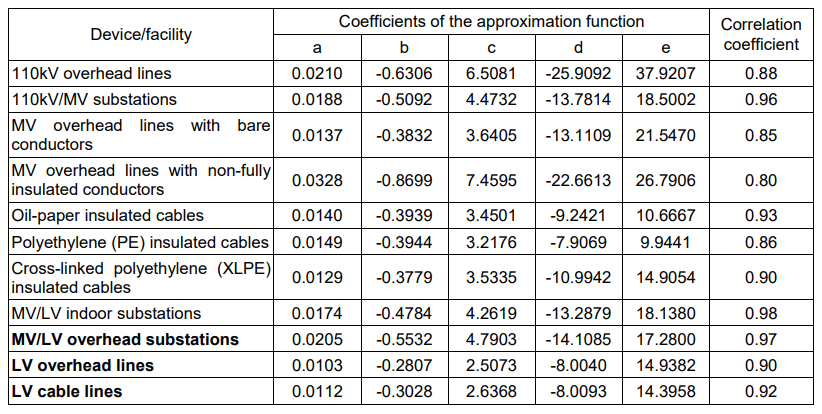

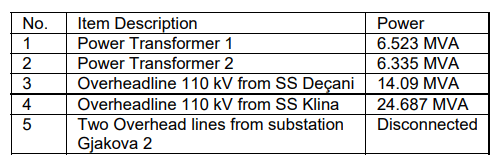

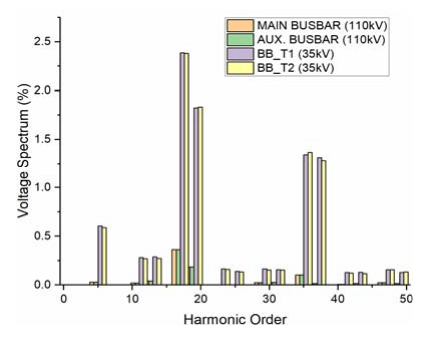

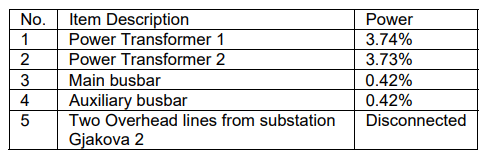

Substation Gjakova 1, 110kV/35 kV has two power transformers 110/35/10 kV (20MVA each), two 110kV transformer bays, four 110kV line bays, one 110kV bus coupler bay, two 100kV line bays (reserve) and nine 35kV bays, as presented in Fig.6. Power flow data in power transformers and power lines, which are connected to substation Gjakova 1, for this specific case are shown in Table 1. THD is analysed for the most sensitive part of the system or substation. Power transformers and power transformer loads are considered the main sources of harmonics [24, 25]. In this study case the Transformer 1, Transformer 2, 110kV main busbar, and 110kV auxiliary busbar loads are taken into the consideration.

Table 1. Power flow table in substation Gjakova 1

THD variations before and after the power transformers are shown in Fig.6.

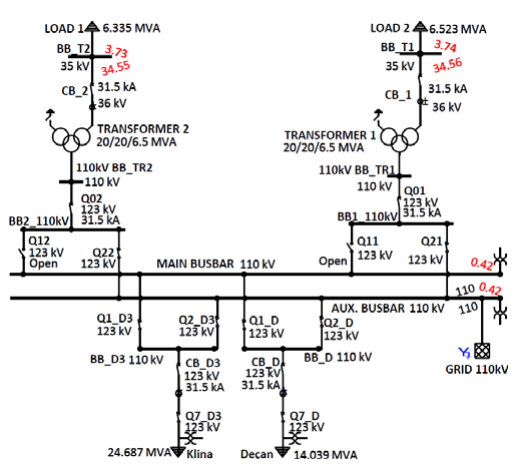

From the simulation part, it can be clearly seen that THD levels are higher (3.75%) in medium voltage 35kV compared with the values for high voltage 110kV (0.42%). Harmonic distortions in terms of 35 kV load and 110 kV power supply side can be well observed from the data shown in Fig.6. The spectrum of harmonic changes is also presented graphically in Fig.7. According to voltage harmonic order, it is seen that THD on the 35kV side of the power transformer is higher than on the 110kV side.

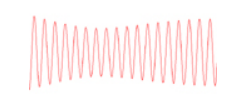

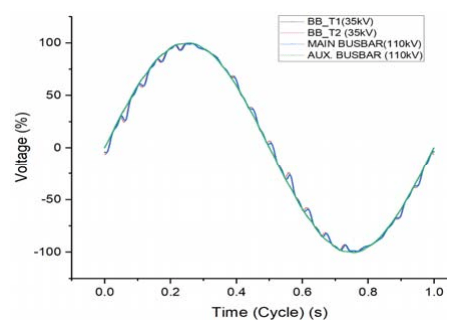

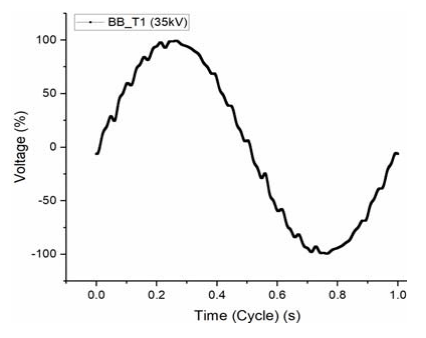

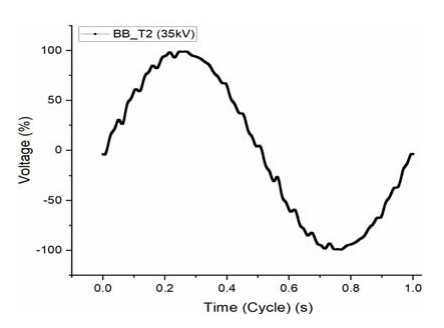

The voltage waveforms for the 35kV and 110kV sides are shown in Fig.8. From this figure it can be clearly seen that the level of voltage harmonics for the 35kV side are 3.74%, Voltage harmonics on 110kV side are 0.42%. In Fig.9 and Fig.10 are shown the voltage waveforms separately for each transformer on the 35kV side.

From the results of the ETAP reports presented in Table 2, there are satisfactory results in terms of voltage levels, harmonics order, and harmonic distortion. Referring to the allowed THD level of voltages and currents in the harmonics, only THD values up to 5% are allowed at the 35kV level.

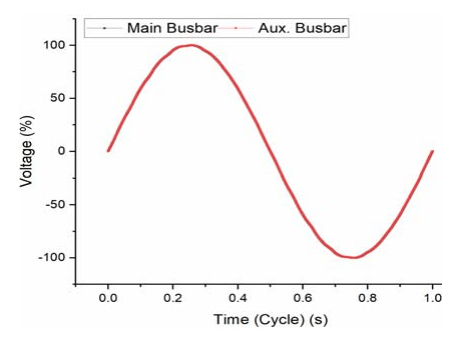

Voltage waveforms for the 110kV main busbar are shown in Fig.11, and THD is quite low, which is characteristic of high voltages and small currents.

In our case, the THD value is 3.74% for the 35kV side of substation Gjakova 1. THD voltage at the 110kV level is allowed to be up to 1.5%. In the Gjakova1 substation, the level of THD voltage is 0.42% on the 110kV side. According to the obtained results, there is no need for additional investment in substation Gjakova 1 regarding power quality improvement.

Table 2. Results from THD simulation in substation Gjakova 1

Conclusion

Monitoring the THD is critical for obtaining accurate data on the amplitude of the harmonic as well as its variation over time. Without simulation, mathematical analysis of THD would be limited. The main case for analysing power quality is Substation 110/35 kV Gjakova 1, and simulations with ETAP Power Station are carried out based on the organizational scheme of equipment in Substation Gjakova 1. The results of simulations for Substation Gjakova 1 are presented in terms of power quality. This indicates that the investment in this substation was highly successful. Based on the obtained results, the maximum level of voltage harmonic distortions in Substation Gjakova 1 on the 35 kV side is 3.74%, while on the 110 kV side, it is 0.42%. According to IEEE standards, for the 35kV level, it is allowed for THD to reach a value of up to 5%, and on the 110 kV side up to 1.5%. In this study, THD is examined at high voltage levels, and it is discovered that THD is considerably low at these voltage levels. This is due to small currents at high voltage levels. Harmonics in the system are proportional to the overall current of the system. Because of the small currents and high voltages at 110kV and 35kV levels, the analysed case study has only low-order harmonics. Gjakova 1 Substation meets all standards for quality electric power supply. The harmonics’ injection frequently has an impact on the motor that first generated them. As a result, harmonics detection and reduction are crucial tasks for the industry today. The paper is based on comparative THD study methodologies at various voltage levels. The purpose of this paper is to recommend THD reduction and control in LV levels where induction machines are connected, and it can be applied to induction machines in thermopower plants in Kosovo where such induction motors (even larger in power) with the same connection configuration are common. There is an acceptable range of THD in 110 kV and it can be applied in all 110 kV substations in the Kosovo Power System.

REFERENCES

[1] P. Sanjeevikumar, C. Sharmeela, Jens Bo Holm-Nielsen and P. Sivaraman, “Power Quality in Modern Power Systems,” Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier, Academic Press, 2021.

[2] S. Elphick, V. Gosbell, V. Smith, S. Perera, P. Ciufo and G. Drury, “Methods for Harmonic Analysis and Reporting in Future Grid Applications,” IEEE Transactions on Power Deliver, vol.32, no. 2, pp. 989-995, 2017.

[3] P. Kuwałek, “Influence of Voltage Variation on the Measurement of Total Harmonic Distortion (THD) by AMI Smart Electricity Meters,” 2021 13th International Conference on Measurement, pp. 159-162, 2021.

[4] K. Sobolewski and J. Sroka, “Voltage THD suppression by autonomous power source – case study,” 2020 IEEE 21st International Conference on Computational Problems of Electrical Engineering (CPEE), pp. 1-4, 2020.

[5] A. Arranz-Gimon, A. Zorita-Lamadrid, D. Morinigo-Sotelo, and O. Duque-Perez. 2021. “A Review of Total Harmonic Distortion Factors for the Measurement of Harmonic and Interharmonic Pollution in Modern Power Systems” Energies, vol. 14, no. 20, 2021.

[6] N. Nakhodchi, T. Busatto and M. Bollen, “Measurements of Harmonic Voltages at Multiple Locations in LV and MV Networks,” 2020 19th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), pp. 1-5, 2020.

[7] C. Hou, M. Zhu, Z. Li, Y. Li and X. Cai, “Inter Harmonic THD Amplification of Voltage Source Converter: Concept and Case Study,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 35, no. 12, 12651-12656, 2020.

[8] M. Benakcha, L. Benalia, F. Ameur and D. E Tourqui, “Control of dual stator induction generator integrated in wind energy conversion system,” Journal of Energy Systems, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 21-31, 2017.

[9] J.K. Phipps, J.P. Nelson and P.K. Sen, “Power quality and harmonic distortion on distribution systems,” IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 476-484, 1994.

[10] N. Berisha, N. Avdiu, R. Stanev, D. Stoilov and S. Morina, “Dynamic modeling of “KOSOVO A” power station synchronous generator,” 2020 21st International Symposium on Electrical Apparatus & Technologies (SIELA), pp. 1-5, 2020.

[11] J.A.X Prabhu, S. Sharma, M. Nataraj and D.P. Tripathi, “Design of electrical system based on load flow analysis using ETAP for IEC projects,” 2016 IEEE 6th International Conference on Power Systems (ICPS), pp. 1-6, 2016.

[12] A. CHUDY, P. A. MAZUREK, “Ultra–fast charging of electric bus fleet and its impact on power quality parameters”, Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, 99 (2023), nr. 1, 294-297.

[13] J. Matas, H. Martín, J. de la Hoz, A. Abusorrah, Y. Al-Turki and H. Alshaeikh, “A New THD Measurement Method with Small Computational Burden Using a SOGI-FLL Grid Monitoring System,” IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics, vol. 35, no. 6, 5797-5811, 2020.

[14] S. Rajasekaran and C. Mahendar, “Comparative Study of THD in Multilevel Converter Using Model Predictive Controller,” 2021 International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Smart Systems (ICAIS), pp. 1559-1563, 2021.

[15] Y. Kou and F. Xiong, “Influence of Phase Angle for Low-order Harmonics on Vibration of an Induction Traction Motor,” 2022 IEEE 5th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), pp. 3736-3740, 2022.

[16] F. BABAA and O. BENNIS, “Steady State Analytical Study of Stator Current Harmonic Spectrum Components on ThreePhase Induction Motor under Unbalanced Supply Voltage,” 2020 International Conference on Control, Automation and Diagnosis (ICCAD), pp. 1-6, 2020.

[17] Y. Wang, L. Tian, L. Zhang and H. Zhao, “Auto-tracking frequency regulation-based energy saving technology for motor systems with dynamic and potential energy load”, IEEE Access, vol. 9, pp. 131806-131814, 2021.

[18] A. H. VanderMeulen, T. J. Natali, T. J. Dionise, G. Paradiso and K. Ameele, “Exploring new and conventional starting methods of large medium-voltage induction motors on limited kVA sources”, IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl., vol. 55, no. 5, pp. 4474-4482, 2019.

[19] M. ZAOUIA, A. FEKIK, A. BADJI, N. BENAMROUCHE, “A thermal model for induction motor analysis under faulty operating conditions by using finite element method”, Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, 97 (2021), nr. 1, 12-17.

[20] H. Lai, W. Lin and G. Pu, “Harmonic Loss Analysis of Threephase Induction Motor Sine Winding,” 2020 IEEE International Conference on Artificial Intelligence and Computer Applications (ICAICA), pp. 1112-1115, 2020.

[21] G. Joksimovic, M. Mezzarobba, A. Tessarolo and E. Levi, “Optimal selection of rotor bar number in multiphase cage induction motors”, IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 135558-135568, 2020.

[22] G. Joksimović, E. Levi, A. Kajević, M. Mezzarobba and A. Tessarolo, “Optimal selection of rotor bar number for minimizing torque and current pulsations due to rotor slot harmonics in three-phase cage induction motors”, IEEE Access, vol. 8, pp. 228572-228585, 2020.

[23] E. Haile, G. Worku, AM Beyene and M. Tuka, “Modeling of doubly fed induction generator based wind energy conversion system and speed controller,” Journal of Energy Systems, vol. 5, no. 1, pp. 46-59, 2021.

[24] N. Nakhodchi, T. Busatto and M. Bollen, “Measurements of Harmonic Voltages at Multiple Locations in LV and MV Networks,” 2020 19th International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), pp. 1-5, 2020.

[25] B. Prebreza, I. Krasniqi, B. Krasniqi, “Analysis of impact of atmospheric overvoltages in Kosovo power system,” International Journal of Power and Energy Conversion, vol.10, no. 4, pp. 512-525, 2019.

Authors: First author is Msc. Ass. Nuri Berisha, E-mail: nuri.berisha@uni-pr.edu; Second author is Prof. Ass.Dr. Bahri Prebreza* corresponding author, E-mail: bahri.prebreza@unipr.edu; Third author is Msc. Ass. Petrit Emini, E-mail: petrit.emini@uni-pr.edu; University of Prishtina, Faculty of Electrical and Computer Engineering, Street ”Sunny Hill”, nn, 10000, Prishtina.

Source & Publisher Item Identifier: PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, ISSN 0033-2097, R. 99 NR 8/2023. doi:10.15199/48.2023.08.21