Published by Nijat Mammadov1, Najiba Piriyeva2, Shukufa Ismayilova3, Azerbaijan State Oil and Industry University ORCID: 1. 0000-0001-6555-3632; 2. 0000-0002-8990-1803

Abstract. The purpose of this study is to analyze the lightning protection systems of wind turbines. One of the main causes of damage to wind electric installations is lightning strikes. In order to reduce the likelihood of damage to these installations, it is necessary to improve the performance that is associated with lightning protection. Early shutdown of a wind turbine to protect against lightning damage can result in a reduction in utilization that must be prevented. Therefore, in order to improve the lightning protection characteristics of wind power installations, it is necessary to study the mechanism of lightning strikes. In this article, two main systems are considered for the analysis of lightning protection systems for wind turbines. This is a grounding system and a system for detecting thunderclouds near wind turbines. This article provides some grounding measures that include modifying the receptor, laying an insulated cable on the down conductor to increase the likelihood of a lightning strike on the receptor. The article also presents a scheme of the formation of thunderstorm leaders and response leaders emanating from the wind turbine blade receptors. The characteristics of wind rotation speed during normal operation, before and after a lightning strike are given. The main types of lightning detection devices are considered. The article presents modern methods and technologies for lightning protection of wind turbines.

Streszczenie. Celem pracy jest analiza systemów ochrony odgromowej turbin wiatrowych. Jedną z głównych przyczyn uszkodzeń instalacji wiatrowych są uderzenia piorunów. Aby zmniejszyć prawdopodobieństwo uszkodzenia tych instalacji, należy poprawić wydajność związaną z ochroną odgromową. Wcześniejsze wyłączenie turbiny wiatrowej w celu ochrony przed uszkodzeniami spowodowanymi przez wyładowania atmosferyczne może skutkować zmniejszeniem wykorzystania, któremu należy zapobiegać. Dlatego w celu poprawy właściwości odgromowych instalacji wiatrowych konieczne jest zbadanie mechanizmu uderzeń pioruna. W tym artykule rozważono dwa główne systemy do analizy systemów ochrony odgromowej turbin wiatrowych. Jest to system uziemiający oraz system wykrywania chmur burzowych w pobliżu turbin wiatrowych. W tym artykule opisano pewne środki uziemiające, które obejmują modyfikację receptora i ułożenie izolowanego kabla na przewodzie odprowadzającym, aby zwiększyć prawdopodobieństwo uderzenia pioruna w receptor. W artykule przedstawiono także schemat powstawania liderów burzowych i liderów reakcji pochodzących z receptorów łopatek turbiny wiatrowej. Podano charakterystykę prędkości wirowania wiatru w czasie normalnej pracy, przed i po uderzeniu pioruna. Rozważono główne typy urządzeń do wykrywania wyładowań atmosferycznych. W artykule przedstawiono nowoczesne metody i technologie ochrony odgromowej turbin wiatrowych. (Badania systemów ochrony odgromowej instalacji wiatrowych)

Keywords: wind electric installation, lighting strike, thunderstorm, receptor, wind rotation speed, grounding system, overvoltage

Słowa kluczowe: instalacja elektryczna wiatrowa, uderzenie pioruna, burza, odbiornik, prędkość wiatru, instalacja uziemiająca, przepięcie

1. Introduction

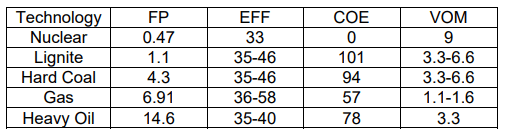

Wind turbines on the horizon hold the potential not only for clean energy production, but also for possible lightning related risks. Providing effective lightning protection for wind turbines becomes a prerequisite to ensure the safety, reliability and long life of these economic activity systems. A thunderstorm is a dynamic meteorological process involving various atmospheric phenomena such as strong winds, rain and lightning. During a thunderstorm, intense movements of air masses occur, accompanied by the formation of clouds and precipitation. However, one of the most exciting and dangerous aspects of a thunderstorm is the lightning. Lightning is a phenomenon associated with electrical discharges in the atmosphere. It occurs as a result of the accumulation and discharge of electrical charge between clouds or between a cloud and the ground. Within the thunderstorm region, various charge zones are formed, where negative and positive charges accumulate in the upper and lower layers of the atmosphere, respectively.

It is important to understand that intense vertical air movements occur inside a thundercloud. Rising currents of warm, moist air can collide with falling currents of cold air, which contributes to the formation and strengthening of an electrical charge. This process leads to further formation of lightning discharges within the cloud and between the cloud and the ground. Sharp objects, such as tall buildings, trees, or mountain peaks, can greatly amplify the electric field and attract lightning. When lightning strikes such objects, energy is rapidly released, which can cause fires, destruction or injury. Modern technologies make it possible to develop structures that are resistant to lightning strikes, such as wind turbines. Manufacturers use a variety of methods to minimize the risk of lightning damage, including conductive mesh, lightning rods, and special grounding systems. However, lightning remains a powerful and unpredictable phenomenon, and the risk of a lightning strike cannot be completely eliminated. It is important to take appropriate precautions during thunderstorms to minimize the risk of injury and damage from lightning [1, 2, 6].

Lightning protection for wind turbines is an important aspect of their safety. Wind turbines taller than 30 meters are more susceptible to lightning strikes because they protrude above the surrounding area and attract lightning strikes. Here are a few precautions and lightning protection systems that can be applied to wind turbines:

1) Grounding: The grounding system is the basis of lightning protection. Wind turbines must have reliable grounding, including deeply driven ground electrodes connected to the main structures of the wind turbine.

2) Lightning rods: Installation of lightning rods helps to attract lightning and discharges past the very structure of the wind turbine. Lightning rods may consist of metal rods or conductors installed at a height and near the wind turbine.

3) Surge protection system: In addition to lightning rods, wind turbines must have surge protection systems to prevent damage to electrical equipment in the event of a direct lightning strike.

4) Lightning protection management: Wind turbines must be equipped with lightning protection management systems that can detect the presence of lightning in the vicinity and take appropriate action, such as shutting down electrical equipment or switching to backup power.

5) Regular maintenance: It is important to carry out regular maintenance of lightning protection systems, including checking the grounding, lightning rods and control systems, to ensure that they are working properly.

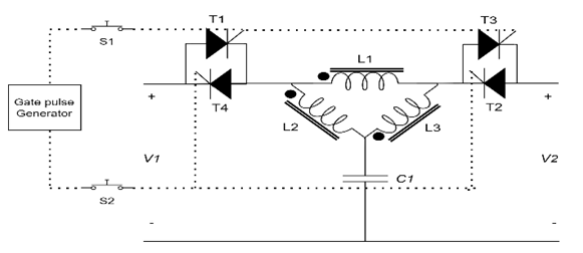

Let’s consider the general lightning protection system for wind turbines. The electronic systems in the nacelle body are sensitive to voltage surges or current pulses. Therefore, the body of the gondola, if conductive, can be used as a Faraday cage that protects electronic systems. If the material of the gondola is non-conductive, to create a Faraday cage, it is necessary to use metal meshes from a metal that has a high electrical conductivity. Distribution cabinets, control cabinets and connecting cables located in the nacelle must also be shielded.

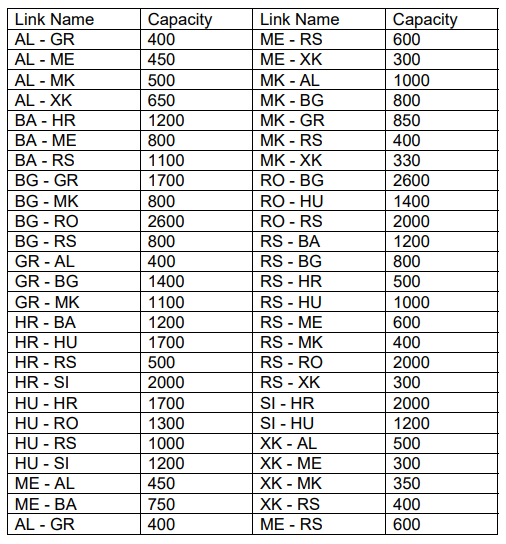

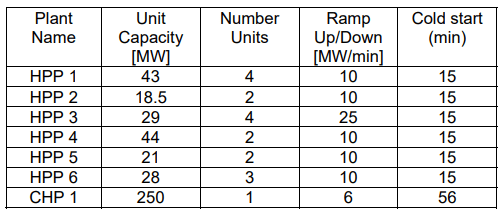

Receptors are receivers that are used to protect the blades of a wind turbine, located at the end of the blades of a wind turbine (Fig.1). The lightning current that enters the receptor is diverted through the descending wire in the blade, gondola, tower and through the grounding system goes into the ground. The blade rarely suffers serious damage if lightning hits the receiver, but the receptor is likely to be damaged if the lightning current is high. For such cases, receivers made of materials with high thermal conductivity have been developed. Not all lightning strikes in wind turbines rush to the receptor. There are cases when lightning penetrates the blade and the discharge reaches the descending conductor inside the blade. This discharge method damages the surface of the blade and, in some cases, can shatter it, resulting in damage to the wind turbine caused by parts of the delaminated blade. Therefore, a lightning protection system for the blades is needed to minimize the possibility of such damage. Some lightning strikes the surface of the blade and directly penetrates the downward conductor inside the blade, resulting in severe damage to the blade. In addition, it has been recorded that lightning strikes to wind turbines are concentrated in areas located approximately 5 mm from the end of the blade. To avoid this, all metal parts are treated with an insulating coating. Some blade manufacturers have developed blades that use insulated wires as down conductors internally. This reduces the likelihood of a lightning strike in the area near the receptor [5, 8-11].

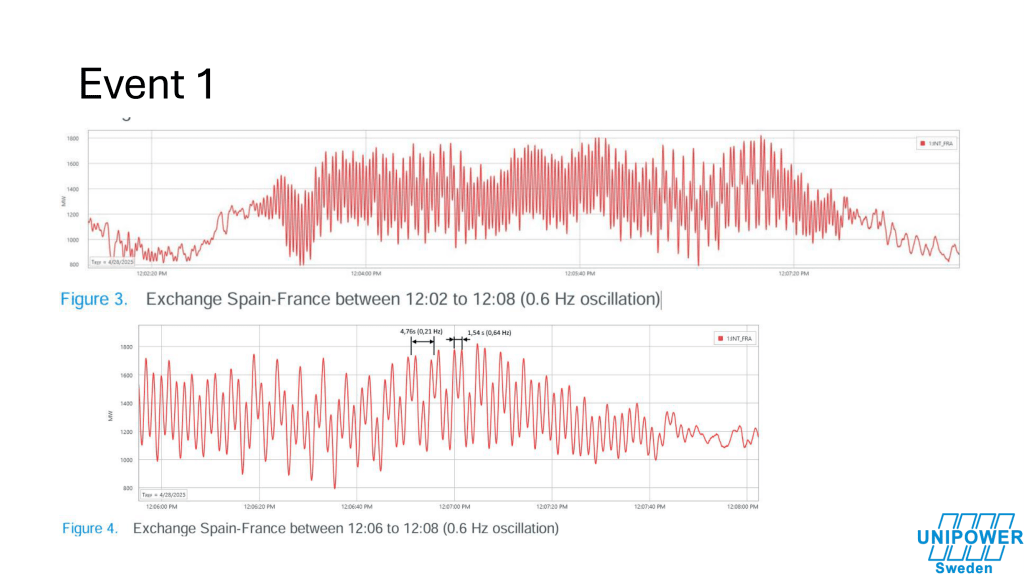

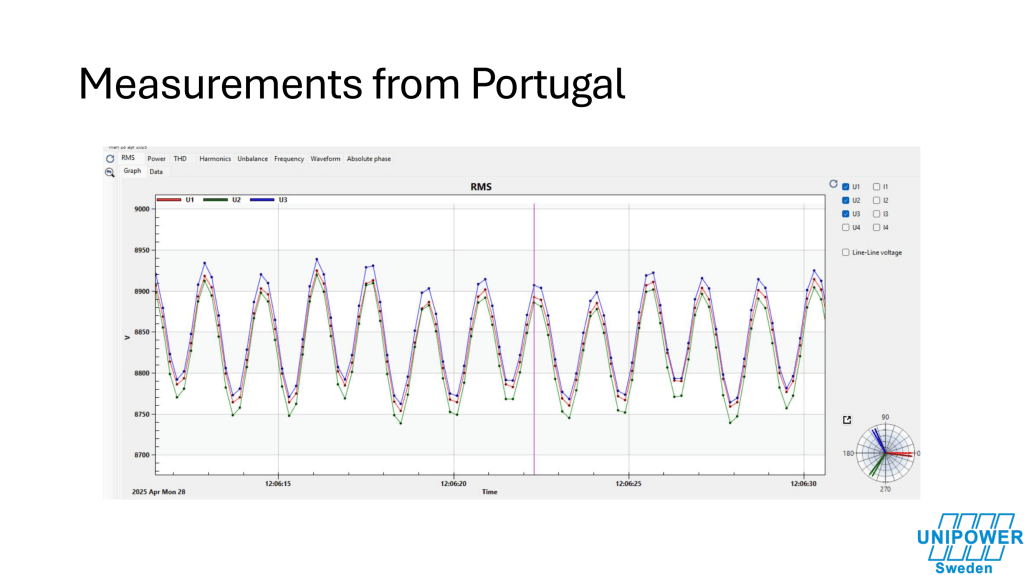

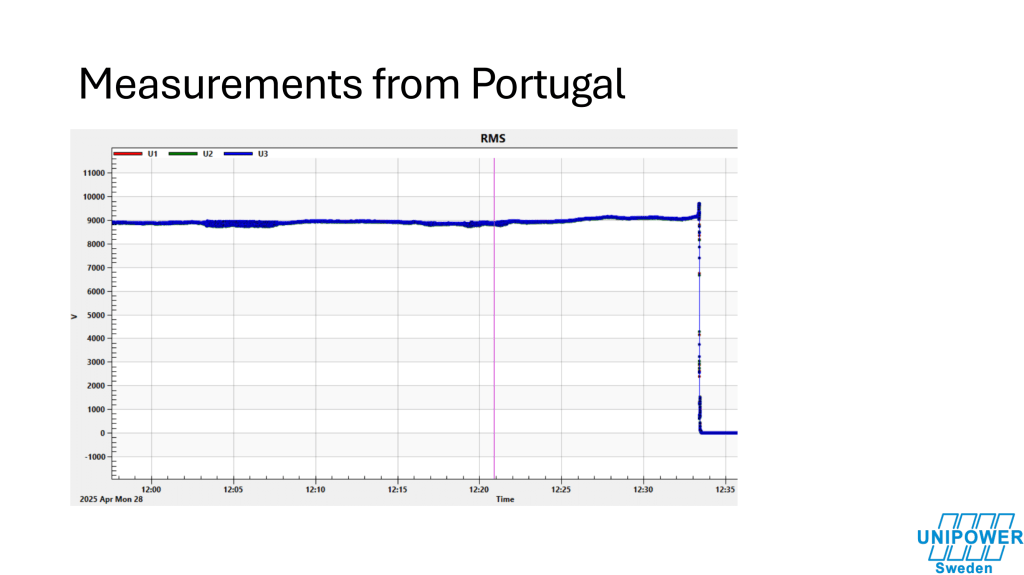

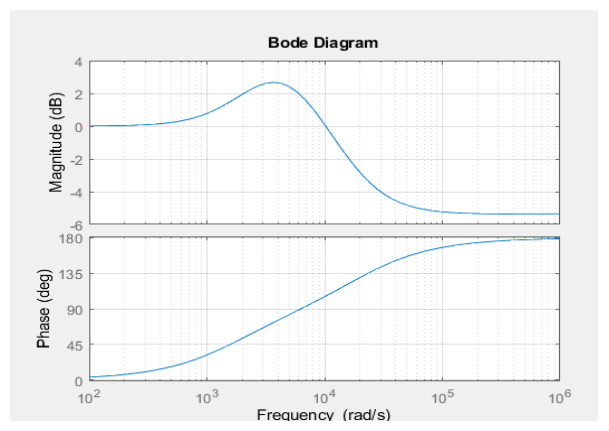

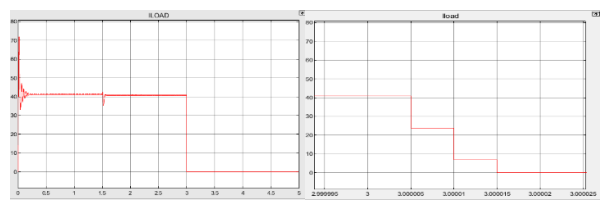

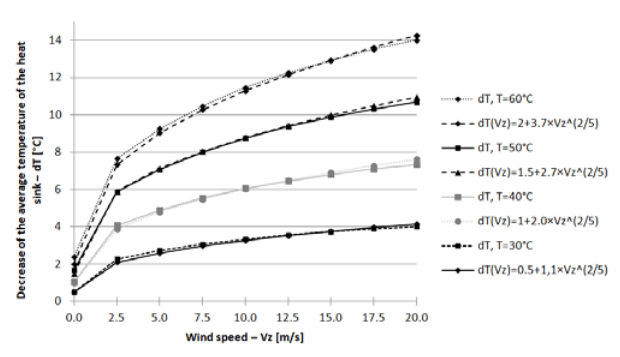

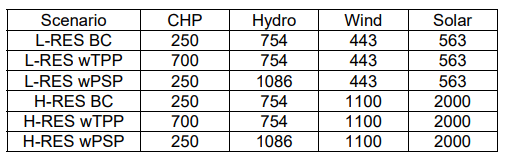

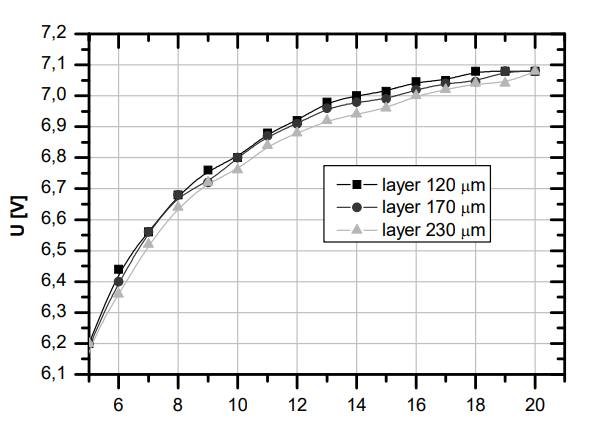

Wind turbine operation before and after a lightning strike. The performance of a wind turbine before and after a lightning strike can vary significantly depending on the damage caused to the structure and its components. Before a lightning strike, the wind turbine operates within normal operating parameters. The blades rotate under the influence of the wind, driving a generator to produce electricity. Control systems monitor wind speed and automatically adjust turbine operation for optimal operation under design conditions. After a lightning strike, the condition of a wind turbine can change significantly. Damage can affect a variety of components, including the blades, electrical system, control equipment, and other parts of the turbine. If the damage was minimal and limited to mechanical components only, the wind turbine can continue to operate with relatively few changes. However, if the electrical system or control components are damaged, the operation of the wind turbine may be impaired. In some cases, the turbine may be disabled to prevent further damage or to ensure the safety of maintenance personnel. After a lightning strike, a thorough inspection and damage assessment must be carried out to determine the extent of the restoration work and ensure the continued operation of the wind turbine is safe [3, 4, 7]. Figure 2 shows the characteristics of wind rotation speed on normal operation, before lightning strike and after lightning strike.

2. Materials and Methods

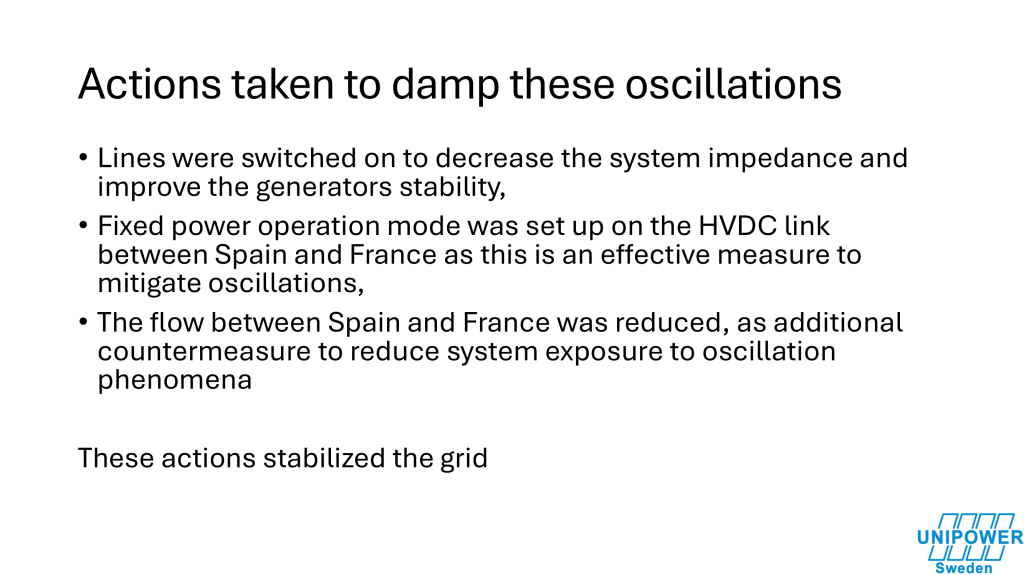

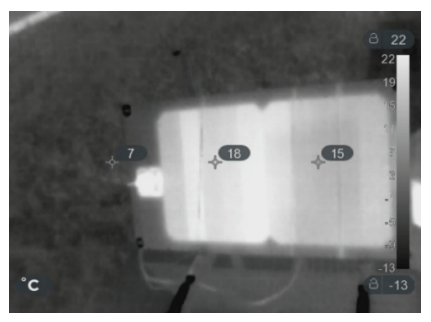

Grounding system. The grounding system of a wind turbine (Fig.3) plays a key role in ensuring safety and protecting the equipment from lightning strikes and surges. It consists of a series of grounding conductors and electrodes that direct electrical current from structures and equipment to the ground. When lightning strikes a receiver, such as a wind turbine blade, the grounding system provides an efficient path for the lightning current, directing it to the ground. This prevents equipment damage and minimizes the risk of fire or electrical shock.

Key components of a grounding system include grounding fixtures at the base of the tower or pole, as well as additional grounding devices, such as ring or deep electrodes, that are installed in the ground around the base of the structure. This creates a low ground resistance, which allows lightning current to be effectively discharged and prevents the rise of ground potential around the wind farm. Additionally, the wind turbine grounding system may include monitoring equipment to monitor the condition of the grounding. This allows any grounding problems to be quickly identified and corrective action taken, thereby reducing the likelihood of equipment damage and ensuring personnel safety. Moreover, wind farm design engineers take into account factors such as local climate conditions and geological features when designing the grounding system. This allows you to adapt the design and location of grounding elements to specific operating conditions, providing optimal protection against lightning and surges.

Overall, a wind turbine’s grounding system is an essential component for ensuring safe and reliable operation during thunderstorms and lightning, and its effectiveness has a direct impact on the protection of equipment, personnel and the environment [12-15].

Lightning detection devices. There are four main types of lightning detection devices:

1) Solenoid coil tower type.

2) Rogowski coil, tower type.

3) Rogowski coil (for ground wire).

4) Rogowski coil (for downstream conductor).

These devices use current sensors that measure lightning current and detect when a wind turbine has been struck by lightning.

Tower type solenoid coil. It is usually installed in a lightning detection device. When lightning strikes a wind turbine, the equipment detects a transient magnetic field created by the lightning current flowing through the installation tower. Due to the low cost and ease of installation, this type of device is the most popular, but it has its drawbacks. If lightning does not hit the wind turbine itself, but in the areas surrounding it, then a voltage appears between the output terminals of the solenoid coil. This voltage may exceed the detection threshold, the device may incorrectly detect both wind blow and installation blow. Manufacturers of this type of equipment have raised the detection threshold to reduce the number of such errors, but the problem still persists.

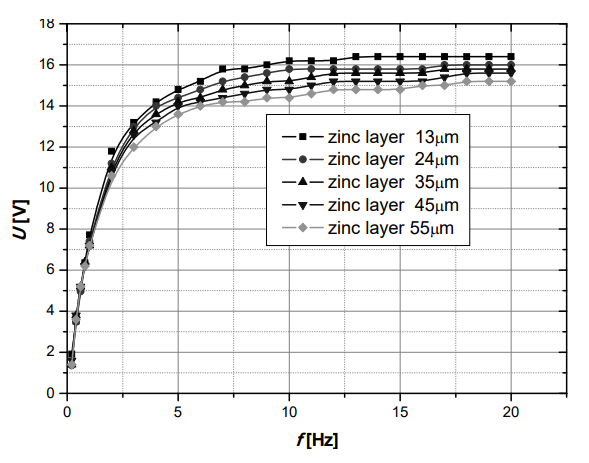

Coil Rogowski tower type. The coil is placed around the tower and is used as a sensor that detects the lightning current flowing through the tower. The sensor does not respond to lightning strikes in the areas adjacent to the wind turbine, which means it allows you to more accurately determine the presence of a lightning strike in the wind turbine. Due to the wide frequency band from 0.1 Hz to 0.96 MHz, the coil can collect lightning current parameters related to turbine damage, such as the maximum lightning current and electric charge. This type of device is expensive. In recent years, functional limitations have been introduced, so its price has come down [16-18].

Rogowski coil (for ground wire). The coil is installed on the ground wire of the grounding system and detects the shunt current when lightning strikes the wind turbine, thereby revealing that the turbine has been struck. Before using the equipment, it is necessary to determine the relationship between the lightning current flowing through the wind turbine and the shunt current flowing through the ground wire on which the coil is installed. Based on this dependence, the detection threshold is set. It must be taken into account that the wind turbine has power electronics and other devices that create noise and in many places constant noise is superimposed on the ground line. Therefore, it is not advisable to use this type of equipment when the noise current exceeds the current threshold.

Rogowski coil (for descending conductor). The coils are attached to the descending (from the receptors) conductors in the blades. When lightning strikes, a current is detected in the wind turbine and it is possible to determine which blade was struck. There are, however, some drawbacks. First, the sensors are installed in the rotating section of the wind turbine, which means that the measuring equipment is required to be attached to the blade conductor inside and fixed at the hub. Secondly, in some wind turbines, the hubs and blades are sealed, so it is necessary to develop a way to communicate between the transmitters installed in them and the receiver located in the nacelle [19-22].

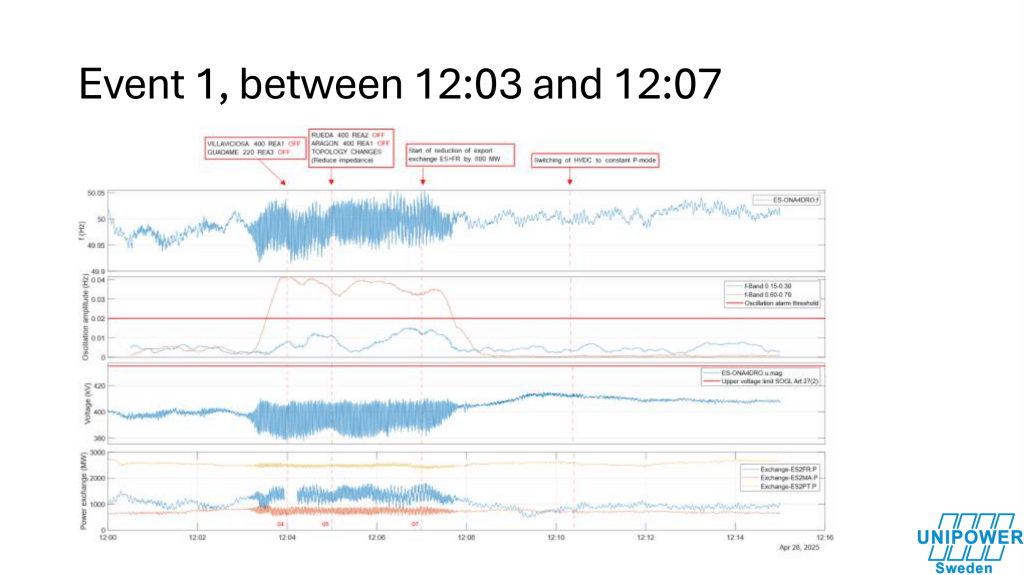

Systems for detecting thunderclouds near wind turbines. Storm cloud detection systems near wind turbines are critical to ensuring the safety of personnel and equipment. Here are some of the main components and methods that can be used in such systems:

1. Lightning detection radar systems: Installation of specialized radar systems that detect lightning near wind turbines. These systems can accurately determine the location of lightning and its proximity to an installation.

2. Meteorological sensors: Placement of meteorological sensors on wind turbines to continuously monitor atmospheric parameters such as pressure, humidity, temperature and wind speed. This data can be used to detect approaching thunderclouds.

3. Equipment condition monitoring systems: Using equipment condition monitoring systems that can detect electromagnetic interference caused by lightning and automatically take measures to protect the equipment.

4. Automated control systems: Development of automated control systems that can automatically adjust the operation of wind turbines in the event of lightning activity, for example, reducing the speed of rotation of the blades or temporarily stopping the operation of the installation [23-25].

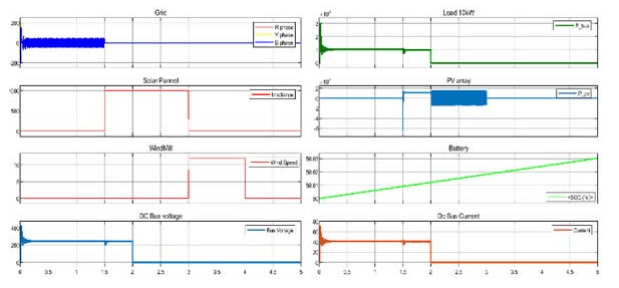

There are two main approaches to detecting thunderclouds near wind turbines. The first approach is based on measuring the electrostatic field around the turbine. As a thunderstorm approaches, this field increases. Research has shown that there is a relationship between this electrostatic field and the likelihood of lightning striking a turbine, and in 85% of cases the plant can be shut down before a lightning strike if the field threshold is determined accurately. However, reducing the threshold value may reduce the likelihood of lightning striking the turbine, but will lead to increased downtime and reduced turbine utilization. The second approach is based on a lightning location system. This system monitors lightning strikes near wind turbines and detects approaching thunderclouds. This method can detect thunderstorms that originate far from the turbines, giving more time to decide whether to shut down the plant. However, for winter thunderstorms, which rarely result in lightning strikes but can develop quickly near turbines, the first method, based on measuring localized electrostatic fields, may be more effective [26-28]. The purpose of these systems is to ensure reliable operation of wind turbines in lightning conditions, minimize risks and increase the safety of personnel and equipment.

3. Conclusion.

In the absence of a lightning protection system for a wind turbine, a lightning discharge may result in damage to control systems, electrical systems, blades, and other mechanical parts. Therefore, when designing wind turbines, it is necessary to carefully consider and identify potential risks and pay special attention to the lightning protection system. For this purpose, an efficient system has been developed using numerical analysis of the electromagnetic field in the grounding structure. In addition, an automatic detection system is proposed that accurately detects lightning strikes, determines the level of damage from the strike, and tells whether the turbine needs to be repaired, whether it is able to continue working. Studies have been carried out to detect the approach of thunderclouds, to determine the probability of impact in wind turbines. The proposed measures make it possible to improve the performance of protection of wind turbines from lightning.

REFERENCES

[1]. Mammadov N., Mukhtarova K. “ANALYSIS OF THE SMART GRID SYSTEM FOR RENEWABLE ENERGY SOURCES”, Journal «Universum: technical sciences”, № 2 (107), pp. 64-67, 2023

[2]. Nijat Mammadov, “Analysis of systems and methods of emergency braking of wind turbines”. International Science Journal of Engineering & Agriculture, Vol. 2, № 2, pp. 147-152, Ukraine, April 2023

[3]. Mammadov N.S., Rzayeva S.V., Ganiyeva N.A., “Analisys of synchronized asynchronous generator for a wind electric installation”, Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, №5, 2023, pp.37-40, doi:10.15199/48.2023.05.07

[4]. Mammadov N.S., “Vibration research in wind turbines”, XV International Scientific and Practical Conference «The main directions of the development of scientific research», Helsinki, Finland, 2023, pp. 345-346

[5]. Csanyi E. “Lightning and surge protection of multi-megawatt wind turbines” // EEP — Electrical Engineering Portal, 2014 –pp. 35-38

[6]. Fisher F. A., Plumer J. A., Perala R. A. “Lightning protection of Aircraft”, 2 edition. Lightning Technologies Inc, 2000 – pp.45-54

[7]. Radicevic B. M., Savic M. S. “Experimental research on the influence of wind turbine blade rotation on the characteristics of atmospheric discharges” // IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion. 2011 – Vol. 26. – pp. 1100–1190.

[8]. Gao L. “Characteristics of Streamer Discharges in Air and along Insulating Surfaces”/ Institute of High Voltage Research, Uppsala University, Sweden, PhD thesis, 2000 – pp.145-146

[9]. Ayub A. S., Siew W. H., MacGregor S. J. “Lightning protection of wind turbine blades-an alternative approach” // AsiaPacific International Conference on Lightning. 2011 – pp. 925–946.

[10]. Yokoyama S., Honjo N., Yasuda Y. “Causes of wind turbine blade damages due to lightning and future research target to get better protection measures” // Intern. Conference on Lightning Protection. 2014- pp. 800–830

[11]. Yamamoto K., Honjo N. Latest trends in technologies for sound operation of wind turbines against lightning // Electr Eng Jpn., 2018

[12]. Glushakow B. Effective lightning protection for wind turbine generators // IEEE Transactions on Energy Conversion. 2007 – Vol. 22. – pp. 200–222.

[13]. Mammadov N.S. “Methods for improving the energy efficiency of wind turbines at low wind speeds”, Vestnik Nauki journal, 2023 – No 4 (61) – T.2 – pp. 230-233

[14]. Mammadov N.S., Aliyeva G.A. “Energy efficiency improving of a wind electric installation using a thyristor switching system for the stator winding of a two-speed asynchronous generator”, IJTPE, Issue 55, Volume 55, Number 2 , pp. 285-290, June 2023

[15]. Rzayeva S.V., Mammadov N.S., Ganiyeva N.A. “Overvoltages during Single-Phase Earth Fault in Neutral-Isolated Networks (10÷ 35) kV”, Journal of Energy Research and Reviews 2023 -13 (1) – pp.7-13

[16]. Rzayeva S.V., Mammadov N.S., Ganiyeva N.A. “Neutral grounding mode in the 6-35 kv network through an arcing reactor and organization of relay protection against singlephase ground faults”, Deutsche Internationale Zeitschrift für Zeitgenössische Wissenschaft, 2023 – №42

[17]. Pastromas, S.; Pyrgioti, E. Protection Measures on Wind Turbines against Lightning Strikes. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Renewable Energies and Power Quality (ICREPQ’17), Malaga, Spain, April 2017 – №4–6 – pp.388–393.

[18]. Kalair, A.; Abas, N.; Khan, N. Lightning interactions with humans and lifelines. J. Light. Res. 2013 – №5 – pp. 11–28.

[19]. Nasiri, M.J.; Homaee, O.; Najafi, A.; Jasinski, M.; Leonowicz, Z. Analyzing the Effect of Lightning Channel Impedance on the Induced Overvoltages in Wind Turbines. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Environment and Electrical Engineering and 2022 IEEE Industrial and Commercial Power Systems Europe (EEEIC / I&CPS Europe), Prague, Czech Republic, 28 June–1 July 2022 – pp. 1–6.

[20]. Ilkin Marufov, Aynura Allahverdiyeva, Nijat Mammadov, “Study of application characteristics of cylindrical structure induction levitator in general and vertical axis wind turbines”, PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, R. 99 NR 10/2023, pp.196-199

[21]. Nijat Mammadov, Ilkin Marufov, Saadat Shikhaliyeva, Gulnara Aliyeva, Saida Kerimova, “Research of methods power control of wind turbines”, PRZEGLAD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, R.100 NR 5/2024, pp. 236-239

[22]. N.M.Pirieva, S.V.Rzaeva, S.N.Talibov “Analysis of overvoltage protection devices in electrical networks” “Internauka”: scientific journal – No. 43 (266). Part 3. Moscow, 2022. pp. 14-17.

[23]. N.M.Piriyeva, S.V.Rzayeva, E.M,.Mustafazadeh. “Evaluation of the application of various methods and equipment for protection from emergency voltage in 6-10 kv electric networks of oil production facilities.” , Internauka, 2022. № 39(262). c.40-44

[24]. Safiev E.S., Piriyeva N.M., Baqırov Q.T.“Analysis of the application of active lightning rods in lightning protection objects.” Interscience: electron. scientific magazine 2023. No.6(276). Pp 14-17

[25]. Ilkin Marufov, Najiba Piriyeva, Nijat Mammadov, Shukufa Ismayilova, “Calculation of induction levitation vertical axis wind generator-turbine system parameters, levitation and influence loop” Przegląd elektrotechniczny – 2024 – No.2 – pp.135-139

[26]. I.M. Marufov, N.S. Mammadov, K.M. Mukhtarova, N.A. Ganiyeva, G.A. Aliyeva “Calculation of main parameters of induction levitation device used in vertical axis wind generators”. International Journal on technical and Physical Problems of Engineering” (IJTPE), Issue 54, Volume 15, Number 1, pp. 184-189, March 2023

[27]. Piriyeva N.M, Kerimzade G.S., “Mathematical model for the calculation of electrical devices based on induction levitators”, IJ TPE Journal, ISSUE 55. Volume 15 . Number 2, (Serial № 0055-1502- 0623), IJTPE – june 2023. p.274-280.

[28]. Piriyeva N.M, Kerimzade G.S. “Electromagnetic efficiency in induction levitators and ways to improve it“ Przeglad Elektrotechniczny. R.99 NR 06/2023, Poland, pp.204-207

Source & Publisher Item Identifier: PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, ISSN 0033-2097, R. 100 NR 9/2024. doi:10.15199/48.2024.09.38