Published by Bill Howe, P.E., Program Manager, EPRI Power Quality Manager

Presented at EPRI PQ and Smart Distribution 2010 Conference and Exhibition:

Transporting You into the 21st Century Distribution System, June 14th – 17th, 2010

Published by Bill Howe, P.E., Program Manager, EPRI Power Quality Manager

Presented at EPRI PQ and Smart Distribution 2010 Conference and Exhibition:

Transporting You into the 21st Century Distribution System, June 14th – 17th, 2010

Published by David Mueller, Manager, Power System Studies, Electrotek Concepts Inc., Knoxville, Tennessee, USA

Email: dmueller@electrotek.com

Published in: 2007 9th International Conference on Electrical Power Quality and Utilisation

Abstract

Transmission systems around the world are increasingly applying capacitor banks on their transmission systems, primarily to support transmission systems and avoid voltage collapse issues leading to blackouts. Another trend is the utilization of underground cable to obtain right of way in corridors sensitive to overhead lines. These trends both leads to harmonic resonance issues. This paper presents three separate case studies of different situations and concludes with some of the general principles that can be derived from an examination of diverse case studies.

Keywords—harmonics; modeling; C-filter; damping; harmonic source characteristics; underground cable; HVDC; transmission; capacitor banks

The study of harmonic resonance issues on transmission systems is unique and difficult for a variety of reasons. First, the transmission system involves a large model that presents practical difficulties for computer simulations. Second, the transmission system can be operated under a variety of contingencies and generation dispatch that leads to different short circuit levels and impedance characteristics. Third, determining the damping affect of loads on the system is important to the results. Finally, transmission system capacitor banks are multi-staged which allows for different harmonic filter configurations, such as the C-filter.

This paper presents three separate case studies of different situations, all illustrating the unique aspects of transmission system harmonic studies as mentioned above. The case studies include the following diverse selection:

A windfarm under construction included 41 total turbines, each with a 2MW capacity. The site was located in a coastal area with excellent wind energy potential. The connection to the transmission system involved a new line of over 20km. Planning permission to install an overhead line was stalled; so to avoid a financial calamity the windfarm developer began planning an underground transmission line.

The transmission grid operator began studying the affects of the 20km underground transmission connector. Three-core cable has much higher capacitance than overhead line, directly as a result of much closer cable spacing. At transmission voltage levels this capacitance becomes very significant, leading to concerns for harmonic resonance.

A preliminary study by the electric utility showed that the cable did introduce harmonic resonance, particularly under a contingency of one-line out, when the resonance was near the 5th harmonic frequency. From this study the electric transmission operator was reluctant to allow the interconnection of the windfarm via the underground cable. Electrotek was hired to perform additional consulting and analysis of the situation.

Harmonic Modeling Software

The SuperHarm™ harmonics package, as developed by Electrotek Concepts, was utilized to perform all of the harmonics analysis. The software utilizes an “admittance matrix solver” approach in combination with constant current sources for harmonic generation. These afore mentioned techniques allow for a direct solution of harmonic response. The software package has been sold for over 12 years and has been extensively benchmarked with test cases for solution accuracy. Electrotek maintains a technical resource area, http://www.pqsoft.com, for users to share technical knowledge on power system simulations. Additionally, the company conducts system studies and training on harmonic analysis.

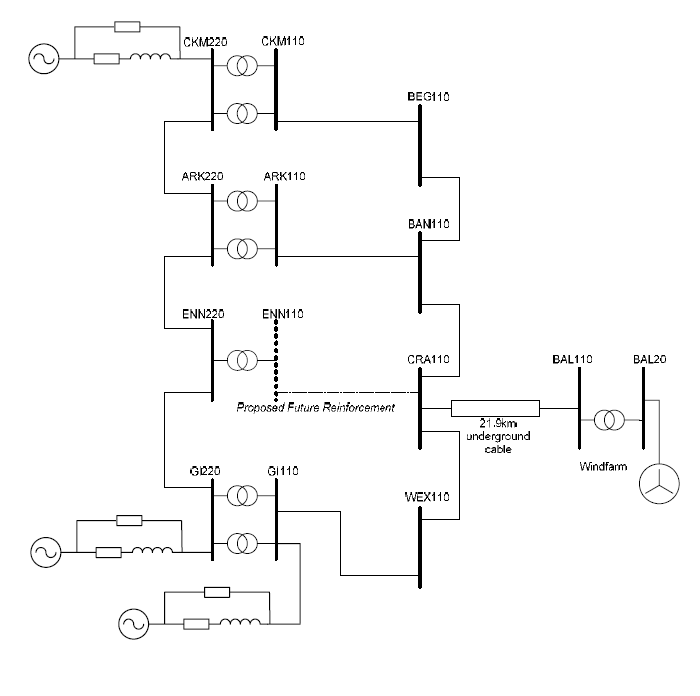

Figure 1 – Network equivalent model

Network Model

A reduced network equivalent model of the entire transmission grid system was developed as shown in Figure 1. The model included Thevenin equivalents at three different supply points, based on short circuit models and studies from the PTI/PSSE software.

The original study similarly used a reduced network for the analysis. The revised network for this later study expanded the original model, providing more detail to evaluate future network improvements and contingencies. The expanded model also allowed harmonic source equivalents to be dispersed about the network, and provided the means to evaluate the resonance concerns on nearby network locations that might have been affected by the interconnection cable or proposed harmonic solutions.

Damping Improvements

Digital computer simulations of power system phenomena at harmonics and other frequencies above nominal (50Hz) tend to present pessimistic (under damped) responses. This is because the ideal mathematical models for components such as lines, cables, transformers, and loads do not typically include enough consideration for frequency-dependant losses (such as skin effect). Generally, this concern is handled by comparing actual measurements with simulation results, and introducing damping elements to the model in order to achieve a closer comparison of the simulations with the measurements. In this particular case there is a not another cable to compare with the one being installed it is difficult to determine the appropriate amount of damping. Thusly, some conservative assumptions must be utilized, along with the consultant’s experience of other situations where some establish general guidelines.

One example of a general guideline that was utilized was the introduction of damping resistors across the Thevenin Equivalents, to provide some damping to the model at higher frequencies.

Harmonic Source Assumptions

Harmonic sources characteristics were developed from measurements taken on the network during a harmonics survey. These typical characteristics were applied at the grid substations as given in Table 1 below. Some adjustment was made on the less characteristic harmonics (3rd, 9th, 11th, 13th) to bring the predicted background levels into line with measurements that were obtained for key locations in the model.

Table 1 – Harmonic source characteristics

| Harmonic Number | Magnitude (% of Load) |

|---|---|

| 3 | 0.5 Balanced 3.0 Unbalanced |

| 5 | 3.2 |

| 7 | 1.5 |

| 9 | 0.2 |

| 11 | 0.4 |

| 13 | 0.2 |

Frequency Scan Results

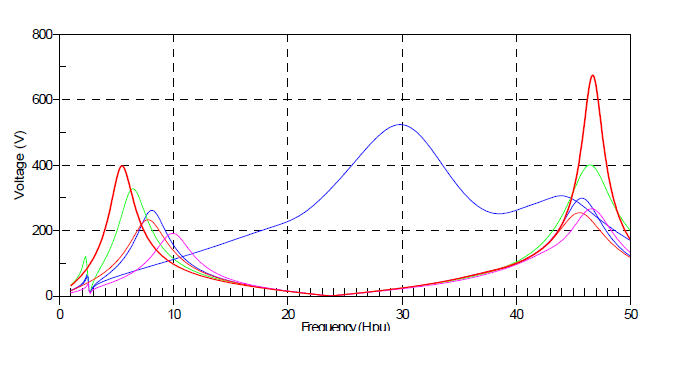

Frequency scans, or “driving point impedance” plots, are frequently used in harmonic analysis to gain physical insight into the response of the network. Figure 2 shows results from various cases, including a line out-of-service contingency that results in resonance at the 5th harmonic frequency.

Figure 2 – Frequency scans of various contingencies

Frequency scan results have limitations, particularly on transmission systems where harmonic sources may be widely distributed and there are many possible sources of resonance. A full harmonic solution case is necessary, where the harmonic voltage distortion is evaluated at all network locations. Table 2 gives some partial results of the harmonic simulations shows that distortion exceeds standard levels when the new cable is installed and especially when one line is out of service.

Table 2 – Summary of harmonic simulation results

| Case | %THD | %H3 | %H5 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Existing | 1.36 | 0.2 | 1.1 |

| New Cable | 2.39 | 0.3 | 1.7 |

| Line 1 Out | 3.08 | 0.2 | 2.5 |

| Line 2 Out | 4.14 | 0.7 | 3.9 |

Solutions

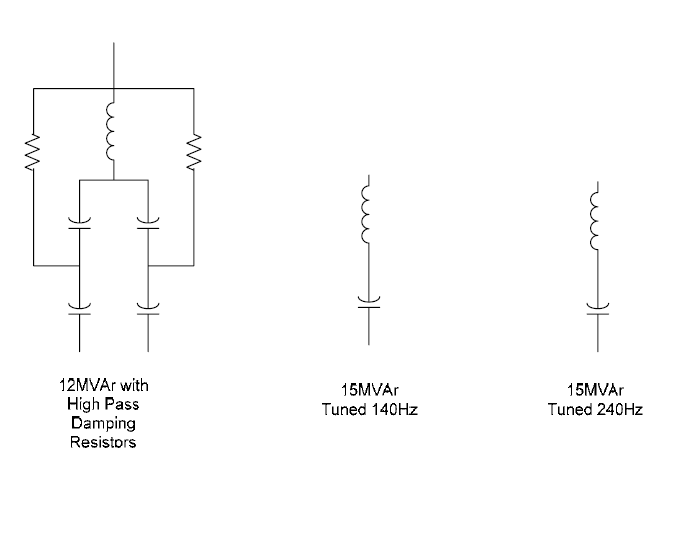

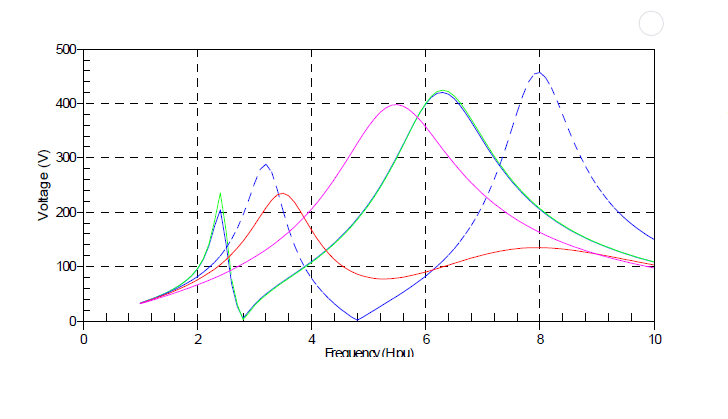

The windfarm developer was interested in providing a harmonic filter that could mitigate the problems of the new underground cable. The filter would allow the connection to be maintained (and wind power sold to the system) under contingency conditions. Figure 3 below depicts the various filter arrangements studied, including a C-Type filter. Figure 4 below gives the frequency scans comparing the various solutions.

Figure 3 – Various filter topologies investigated

Figure 4 – Frequency scans of various solution alternatives

History Description

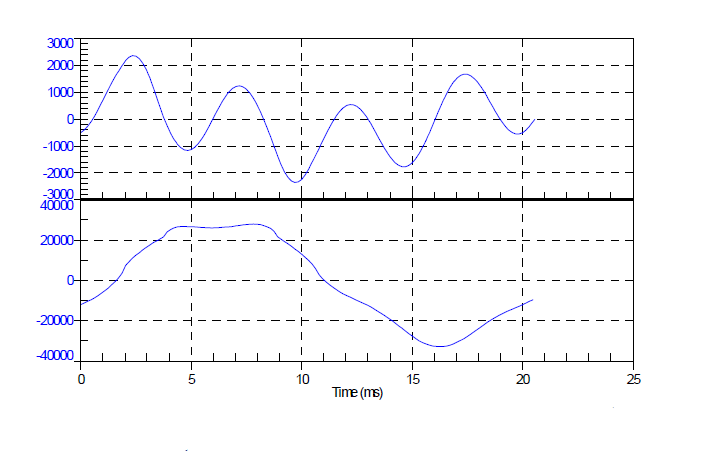

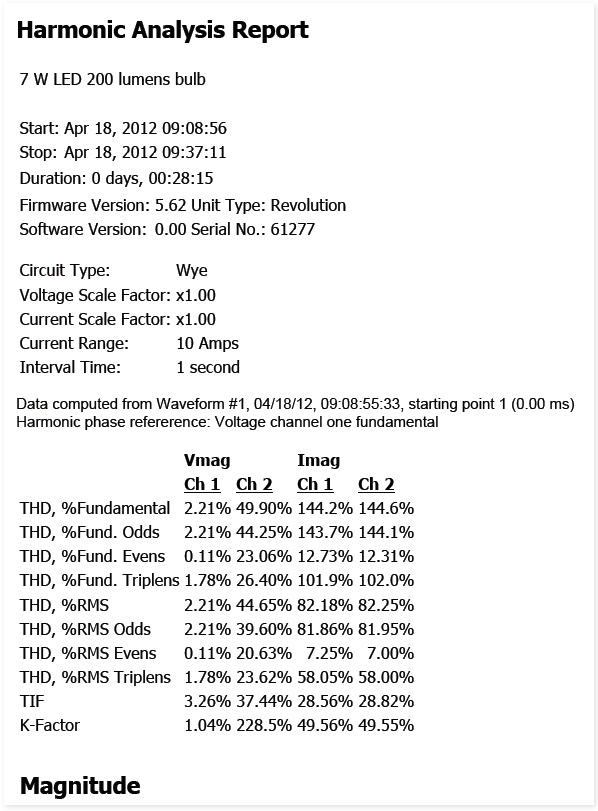

Repeated capacitor failures occurred at a tuned harmonic filter at a transmission substation, connected to the 525kV system. High levels of current were absorbed by the bank (THD=169%, Irms=200%) at the time of one of the failures. The current had an unusually high content of 4th harmonic frequency (Figure 5).

Figure 5 – Current and voltage waveform captured just prior to a failure of the bank

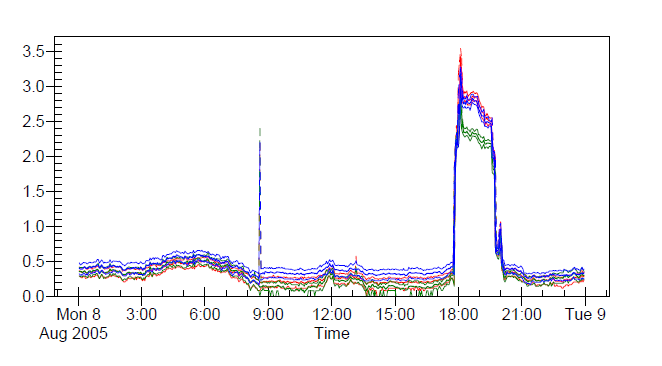

The timing of the incidents clearly identified mono-pole operation of a nearby HVDC terminal as the culprit of the failures. Figure 6 shows the trend of harmonic voltage THD at the affected substation during one of the events. DC bias, similar to that of GIC (Geomagnetic Induced Currents) phenomena, caused high transformer excitation currents rich in harmonic spectrum [1].

Figure 6 – Time trend of harmonic voltage distortion

System Description

The substation was connected to the 525/242kV system with a 750MVA autotransformer with a 34.5kV tertiary. The 34.5kV busbar supplied reactive compensation consists of three main units on the 34.5kV bus:

These units were initially designed to provide reactive power compensation while avoiding problems at characteristic (i.e. 3rd, 5th, 7th) harmonic frequencies, and also to minimize transient switching concerns. They were properly sized with higher voltage ratings to accommodate the voltage rise through the reactors.

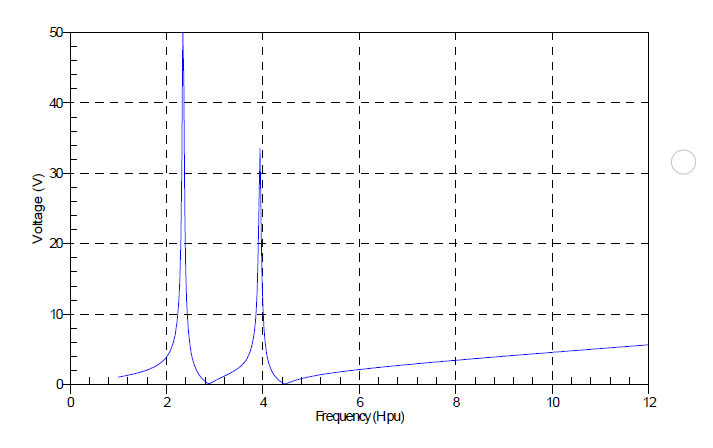

Figure 7 – Frequency scan at the 34.5kV bus

Harmonic Simulation Results

Harmonic simulations confirmed that the configuration of the capacitor banks as harmonic filters results in a series resonant condition at the 4th harmonic frequency (Figure 7), where the bank absorbs excessive 4th harmonic current. During normal conditions there are very few sources of fourth harmonic current. However, during the monopole operation of the HVDC terminal the DC bias results in high transformer excitation current, rich in 4th harmonic content (Table 3).

Table 3 – Transformer full load current under DC bias

| H | Magnitude |

|---|---|

| 1 | 825.213 |

| 2 | 212.198 |

| 3 | 141.465 |

| 4 | 94.3101 |

| 5 | 35.3663 |

Figure 8 shows the simulation results for the waveforms of the voltage and currents (144Hz and 223Hz tuned units). The results show that even with just one transformer in DC bias (and the effect likely involved other units) the filter tuned near the fifth harmonic will absorb a high amount of fourth harmonic current.

Figure 8 – Simulation results for the 34.5kV bus

Solution

Simulations confirmed that the reconfiguration of the capacitor banks, either tuning all banks to 144Hz, or reconfiguring as C-Type filters would resolve this problem. For future banks it is probable that the 144Hz configuration is best although this requires higher voltage rated capacitors. For the existing bank it is easiest to reconfigure as a C-Type filter, as the existing capacitor bank can be reconfigured.

Case History Description

Four identical 52.8MVAr capacitor banks are installed at a transmission substation serving a large city on separate and distinct buses that are numbered 1, 2, 3, and 4. During normal operation of the two banks on buses 2 and 4, voltage total harmonic distortion (THDv) was seen to range about 4-5%. While these levels are probably acceptable for short term operation, they exceed the recommended limits of the IEEE- 519 Standard [2] for harmonics as shown in Table 4 below.

Table 4 – IEEE-519 harmonic voltage limits

| Bus Voltage | Maximum Individual Harmonic Component | Maximum THD |

|---|---|---|

| 69kV and below | 3.0% | 5.0% |

| 115kV to 161kV | 1.5% | 2.5% |

| Above 161kV | 1% | 1.5% |

No appreciable harmonic distortion issues were detected from the operation of banks 1 and 3. A comparison in Table 5 of the available short circuit levels at the substation shows that banks 1 and 3 have a higher fault current availability and so they are less likely to cause harmonic resonance concerns.

Table 5 – Available fault levels at the substation

| Bus | 3 Phase MVAsc | 52.8MVAr H resonant |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 4762 | 9.5 |

| 2 | 3189 | 7.8 |

| 3 | 4490 | 9.2 |

| 4 | 3117 | 7.7 |

Later, when the banks 2 and 4 were operated during a lineout contingency harmonic voltage distortion levels (THDv) of about 10% were experienced. At the same time the current harmonic distortion in the capacitor bank exceeded 50%. These levels of harmonic distortion are clearly detrimental to power quality, and should be avoided for all but the briefest periods of time (minutes). Also the nearby distribution substation experienced some nuisance tripping of protective devices.

The prudent step of reducing the size of Banks 2 and 4 was done by reducing one (of four) strings of parallel capacitor arrangements, derating the size of the bank to 39.6MVAr. A harmonic study of the situation was undertaken.

System Model

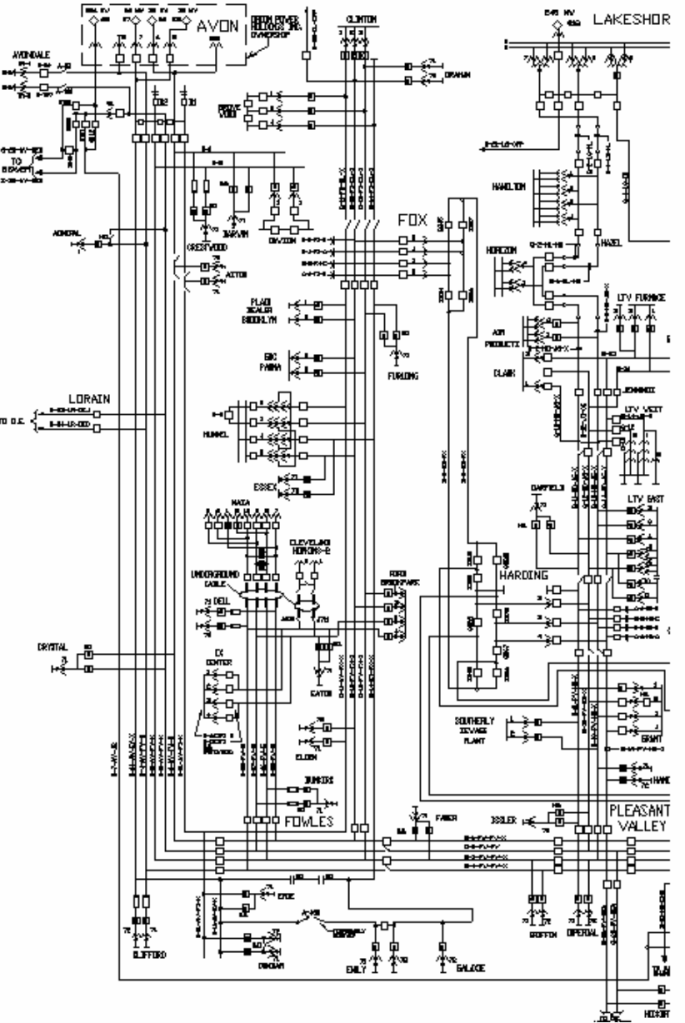

A fairly extensive transmission system network was used for the study. The figure below represents the part of the network that was included in the study. In the end the model included over 900 buses. As capacitor banks for reactive power compensation were distributed about the transmission system, it was necessary to develop such a large model. Impedance data for the model was imported from the short circuit model of the network and facilitated by spreadsheets and batch files. Every three-winding transformer of the system had to be checked against the original test reports, as the impedance values did not always transfer properly through the short circuit program.

Figure 9 – Partial diagram of the system modeled

Simulation Techniques

Loading information from various system buses was used to inject harmonic sources. Table 6 gives the harmonic source characteristics that were used as a percentage of the load. The harmonic source characteristics were adjusted to obtain agreement with available harmonic measurements.

The system supplies some very large industrial loads that contribute a relatively high percentage of harmonic loads. Ideally the largest industrial loads would be characterized for their harmonic content, but such detailed measurements were not available.

Table 6 – Harmonic source characteristics

| Harmonic Number | Magnitude (% of Load) |

|---|---|

| 3 | 0.5 |

| 5 | 8.0 |

| 7 | 3.0 |

| 9 | 0.3 |

| 11 | 1.5 |

| 13 | 1.0 |

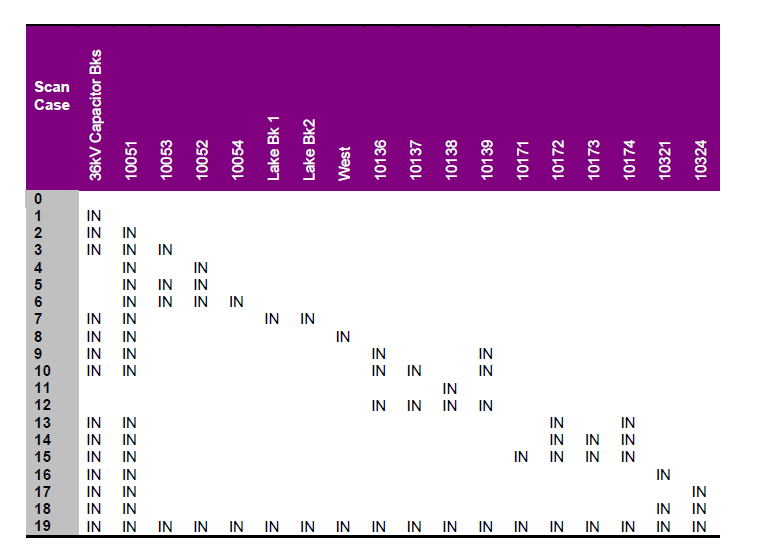

Figure 10 depicts a list of simulation cases where various capacitor banks were in/out of service. Both frequency scans and simulation cases were run with the various configurations. These results allowed insight into the effects of different units. Some units would introduce objectionable resonance, other units would tend to alleviate problems by shifting resonance conditions.

Figure 10 – Case list of simulations

One factor critical to the analysis was considering contingency conditions, when various lines would be out of service. Lines going to substations with major capacitor banks are very important, as the fault level is often greatly reduced. This in turn affects resonant frequency, and is often a limiting factor in the design of the capacitor bank.

Study Results

Banks 1 and 3 have a strong enough supply that they are not expected to cause any harmonics problems. Even during one-line-out contingencies, the source is strong enough to avoid problems at the 5th or 7th harmonic frequencies.

Various frequency scans given the report showed that Buses 1 and 3 are affected by the operation of certain other capacitor banks, but not all of them. Many times these effects occurred at the 11th and 13th harmonic frequencies and were not found to create operational issues.

The distribution system had 36kV capacitor banks that were modeled in this study. In this particular case they were found to have little effect on the results. However, in a subsequent study of a different network area, distribution capacitor banks were found to have an important mitigating effect.

Some problems were encountered as some of the simulation results did not match well with the measurement results. Particularly on bus 4, it was found that the fault levels reflected contributions from large industrial motors and generators that were not always in service. The fault levels in the model were deemed to be higher than those actually available during the measurements. When some adjustments were made for these realistic conditions, the results matched more closely.

The study of harmonic resonance issues on transmission systems is unique and difficult for a variety of reasons. First, the transmission system involves a large model that presents practical difficulties for computer simulations. Second, the transmission system can be operated under a variety of contingencies and generation dispatch that leads to different short circuit levels. Determining the damping affect of loads on the system is important to the results. Finally, transmission system capacitor banks are multi-staged which allows for different harmonic filter configurations, such as the C-filter.

[1] R.A. Walling, A.H. Khan; “Characteristics of transformer exciting current during geomagnetic disturbances”, IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, Vol. 6, No. 4, October 1991.

[2] IEEE 519 “Recommended Practices and Requirements for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems” 1992.

Published by Daniel Sabin, Senior Principal Architect, Schneider Electric, Andover, Massachusetts, USA

Email: daniel.sabin@se.com

Application Note

06-01-2015

Published by Radian Research, Inc.

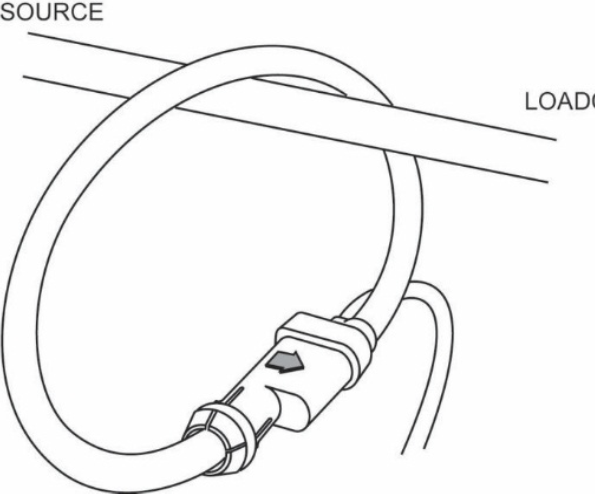

Trademarked flex CT interface WideRangeFlexCT™ measures currents from 1A to 2500A without requiring the user to set specific ranges. Internally there are 3 measurement ranges that are automatically switched between.

The measurement error depends on which range is active, these ranges are 1.00A – 18.00A, 18.0A – 180.0A and 180A – 2500A.

The total measurement error will depend on different factors: the component tolerances of the electronic interface, the manufacturing tolerances of the flex CT coil and the position of the flex CT with respect to the conductor. For minimum positional error, the ideal position is for the flex CT loop to be perpendicular to the conductor with the conductor passing through the center of the loop. In field installations it is difficult to ensure that the conductor passes through the center of the loop, so we calibrate the flex CTs with the conductor passing perpendicular through the loop but positioned on the edge of the loop at the farthest point from the flex connector.

With the conductor positioned the same as during calibration the measurement errors are:

Non-ideal positioning can add an additional 1% of reading error.

Limited resources or need a solution quickly?

If you need additional information about your project just contact us, we are here to help. We can support you at any level from telephone support, or on-site solutions for a reasonable price.

Contact us at radian@radianresearch.com or call 765-449-5500. Be assured that we want to be your partner in success!

Published by E. Hering, Dresden (Germany)

Earth resistance is a key parameter in determining the efficiency of earthing systems. In this article we look at the measurement of earth resistance

1 A Few Fundamentals

1.1 Earth resistance and earth impedance

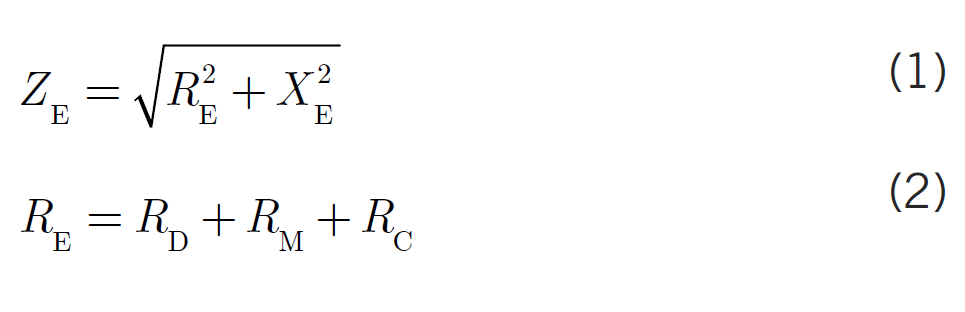

The efficiency of an earthing system is principally determined by its impedance ZE. As can be seen from figure 1, the earth impedance can be expressed as in equation (1):

As shown in equation (2), the earth resistance RE is the sum of the dissipation resistance RD, the resistance of the metal conductor that serves as the earth electrode RM and the resistance of the earthing conductor RC, which runs between the main earthing busbar and the earth electrode. The dissipation resistance RD is the resistance between the earth electrode and the surrounding soil. The reactance of the earthing system XE can be expressed as:

with

XM reactance of the metallic earth electrode

XC reactance of the earthing conductor.

For AC supply current the reactance of the earthing conductor is only significant in the case of extended horizontal earthing strips or long earth rods. In all other cases, the difference between earth impedance and earth resistance is so small that frequently no distinction is made between these two quantities. The relevant industrial standards also treat earth impedance and earth resistance as identical.

As earthing measurements are carried out using an AC supply, it is actually the earth impedance that is measured. If the measurement frequency is greater than 50 Hz, a slightly larger earth impedance is displayed. However, overestimating the earth impedance is not a problem, as it errs on the side of safety.

Figure 1 Vector diagram of impedance in an earthing system

RD dissipation resistance; RE resistance of the earthing system (earth resistance); RM resistance of the metal conductor that acts as the earth electrode; RC resistance of the earthing conductor (e.g. connection lug, cable); XE reactance of the earthing system; XM reactance of the metal conductor that acts as the earth electrode; XC reactance of the earthing conductor; ZE earth impedance; ϕ impedance angle.

1.2 Requirements for earthing measurements

Earthing measurements are necessary whenever compliance with a specified earth resistance or a particular earth impedance is required, as is the case in the following earthing systems:

In the case of lightning protection systems, earthing measurements must be made even when there is no requirement to comply with a specific value. The results of repeat tests must be compared with those of earlier measurements.

1.3 Standards for measuring instruments

The standards contain the requirements that have to be met by the manufacturers of measuring equipment. For users, these standards serve only informational purposes.

In low-voltage systems earthing measurements must be made using equipment that complies with the VDE 0413 standards (VDE: Verband der Elektrotechnik Elektronik Informationstechnik e.V./ engl.: Association for Electrical, Electronic & Information Technologies) (see [3], sec. 61.1). All equipment must comply with the specifications in IEC 61557-1:2007 [4]. In addition, equipment must also comply with the following standards depending on the type of device or measuring method for which it is used:

Equipment manufactured in accordance with earlier editions of the VDE 0413 series of standards can of course also be used.

1.4 Selecting the right measuring equipment

It is not enough for users to simply follow the (frequently unclear) instructions provided by the manufacturer, they need to be aware of and understand the measuring method they want to apply. Measuring instruments that do not make it clear which measuring method is being applied should not be used.

Before purchasing equipment, users should request technical descriptions of the devices of interest as well as their performance data and, if possible, instruction manuals, and should assess the equipment on the basis of this documentation.

1.5 Avoiding hazards and measuring errors

The process of measurement and any accompanying procedures (e.g. breaking standard connections and making non-standard connections) must not pose a safety hazard ([3], sec. 61.1.3). The magnitude of the test voltage or the test current must be limited (see sections 3.1 and 4.1). Before breaking a connection that is required for electric shock prevention, the entire power installation must be disconnected from the supply and locked out to prevent it being switched on again.

Any measurement that involves breaking connections (e.g. opening the inspection joint of a lightning protection system) must never be carried out during a storm or whenever a storm could be expected. Failure to comply could be hazardous, particularly for the person performing the operation. After the measurement has been completed, any connections that were broken must be properly restored.

If the test current is split so that part of it runs parallel to the earth electrode being measured, the earth resistance displayed by the meter will be too small. The person conducting the measurement must therefore be aware of everything that is connected to the earth electrode under test [8]. Measurements must only be carried out by competent persons.

1.6 Taking the effects of weather into account

The specific resistance of soil decreases with increasing temperature and increasing soil moisture levels. Whereas these effects are of minor consequence for foundation earth electrodes in buildings with a basement or for long (vertical) rod electrodes, they have to be taken into account in the case of horizontal surface earth electrodes.

Measurements made during cold, dry weather remain unaffected, but measurement data recorded in warm weather or after a rain shower have to be adjusted upward.

1.7 Assessing measurement results

Earth resistance meters are not error free. Measurement errors can occur even if the conditions specified in the relevant standards and instrument instruction manuals are complied with and even in the absence of interference effects. The magnitude of an instrument’s operating error is listed on its technical specification sheet or in its instruction manual. In those methods of measuring earth resistance that draw current directly from the power source (see sections 2.4 and 4), additional measurement uncertainty can be caused by random current and voltage fluctuations in the supply during the measurement.

Examples of possible operator errors include:

Results from first-time measurements should be compared with the project specifications, results of repeat tests should be compared with those of earlier measurements. If significant differences are apparent, the possible causes of the discrepancy should be determined. The influence of weather on the measurement results and how this can be taken into account is discussed in section 1.6.

1.8 Test report

Measuring earth resistance is only one of several tests that have to be performed on earthing systems [9]. In general, the results from all the tests are contained in a single test report. The measurements performed and any accompanying action that is taken must be described precisely so that they can be reproduced at a later date. Information that must be provided includes:

The results of the measurement must be stated clearly and unambiguously. This also applies to any weather-related adjustments of the results that may have been made.

The test report is required by

2 Overview of Measurement Methods for RE

2.1 Principles

There is a wide degree of variation in the internal circuitry of the measuring instruments used and the layout and arrangement of the external measuring circuits. However, a common feature of all the methods is that they determine the earth impedance by measuring the voltage across the earthing system for a known test current. Leads that carry the test current outside of the instrument are shown in red in the diagrams.

Known measurement methods are listed in table 1. The underlying circuit principles are shown in figures 2 to 4. The unusually long names given here to the various methods ensure that the methods can be distinguished unambiguously.

Although there are clear differences between the individual measurement methods, no one particular method can be said to be ideal. Each method has its own particular disadvantages such as limited applicability, electric shock hazard, larger measurement errors or requiring greater time and effort to complete. The various advantages and disadvantages of the individual measurement techniques are described in more detail in sections 3 and 4. All of the methods discussed must only be carried out by competent persons exercising due care and attention. In those methods that do not draw current directly from the supply (columns 1 to 6 in table 1), the measurement frequency used

will be at least 5 Hz above or below the frequencies 16.7 Hz, 50 Hz and integer multiples thereof. This prevents interference from supply frequency currents (‘interference currents’) that can falsify measurement results.

In those methods that do draw current directly from the supply (columns 7 to 9 in table 1), it is of course essential that the supply frequency and measuring frequency are identical. This means that the interference effects mentioned above cannot be ruled out when such methods are used. However, these methods are simpler to perform and offer advantages in terms of their applicability.

Table 1 Overview of earth resistance measuring methods

2.2 The balanced-bridge method

The balanced-bridge method as described by Behrend is one of the techniques for measuring earth resistance that does not involve drawing current directly from supply. Earth resistance meters based on this method are no longer manufactured, as other more user-friendly instruments have now been developed for the same sorts of applications. These new meters use the so-called current-voltage method, which also does not involve current being drawn from the supply. Nevertheless the balanced-bridge method is described here because it is of fundamental importance to the development of earth resistance measurement techniques and because meters based on this method are still in use.

The measurement circuit for the balanced-bridge method is shown in figure 2. The method involves driving an auxiliary earth electrode1) and a probe2) temporarily into the soil. When the earth meter is in its balanced state, there is no current flowing in the probe. The resistance to earth of the probe has therefore no influence on the measurement result; it simply lowers measurement sensitivity. Information on the alignment and separation of the auxiliary earth electrode and the probe is provided in section 3.

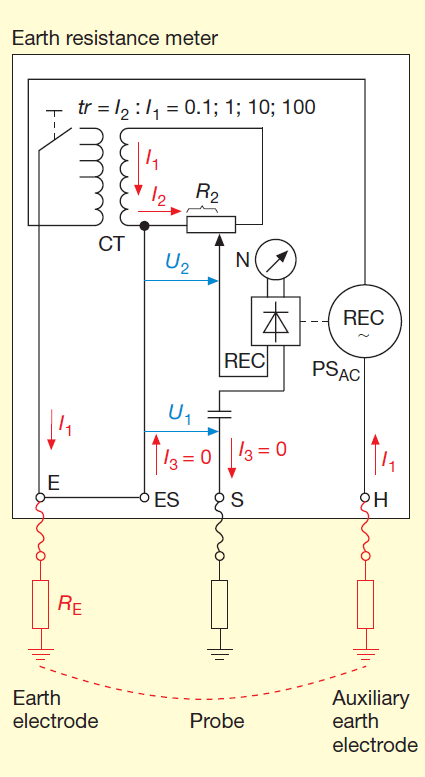

The AC power source PSAC is located between the connection point for the earth electrode under test (socket E) and that for the auxiliary earth electrode (socket H). The AC source is connected in series with the primary winding of a current transformer CT. Connected to the secondary winding of the current transformer is a variable voltage divider. The setting chosen for the left part of the divider R2 (‘reference resistance’) is displayed on the scale on the voltage divider’s control unit. A null detector N with a rectifier REC in series is located between the variable tap point of the voltage divider and the connection point for the probe (socket S). The rectifier is driven by the AC power source. A capacitor C prevents any DC current from flowing across the probe. One end of the voltage divider is connected to the earth electrode being measured via the instrument sockets ES and E. The transformation ratio tr of the current transformer can be switched to achieve the required measurement range.

When balanced, the current I3 in the probe is zero. The same current I1 therefore flows in the auxiliary earth electrode and in the earth electrode under test. Additionally, the voltages U2 (‘reference voltage’) and U1 are of the same size. The voltage U1 corresponds to the earth electrode voltage that drives the test current I1 in the earth resistance RE of the test object E, whereas U2 is the voltage drop that maintains the current I2 (‘reference current’) in the reference resistor R2. The potential drops obey Ohm’s law as expressed by the equations U1=I1 · RE and U2=I2 · R2. If the transformation ratio of the current transformer tr = 1:1, then I2 = I1 and the value of the earth resistance RE is equal to the selected reference resistance R2. The earth resistance can therefore be read off the voltage divider scale mentioned above. If another transformation ratio is used, this must be multiplied by the value of the reference resistance R2, i. e. RE=tr ·R2.

Figure 2: The balanced-bridge method

REC rectifier; I1 test (or measuring) current; I2 Reference current; I3 current whose magnitude is zero when bridge is balanced; C capacitor; N null detector; RE earth resistance being measured; R2 reference resistance; CT current transformer; U1 Voltage

across earth electrode under test; U2 reference voltage; tr transformation ratio of the CT; PSAC AC power supply.

2.3 Other measurement methods without supply current

Another group of methods for measuring earth resistance that do not draw current directly from the supply are the so-called current-voltage techniques illustrated in figure 3. The earth resistance RE is determined from the voltage UM that appears across the earth electrode and across the sockets ES and S, and the measured current I.

Figure 3 simply illustrates the principle of the measurement and shows only a small part of the complex circuitry within the earth resistance meter. Usually, the voltage UM and current I are not shown separately and the meter only displays a digital reading of the earth resistance RE. If the AC supply source PSAC is a constant-current generator, the earth resistance can be displayed directly on the voltage meter. When the balanced-bridge method was first developed, the only exterior circuit known was that shown in figures 2 and 3a). It was therefore usual to consider the circuitry inside the meter and the exterior circuit as a single entity. However, as indicated in columns 2 and 3 in table 1, the same meter can be used for measurements with the exterior circuits shown in figures 3b) and 3c). Equally, the earth resistance meters used for the current-voltage methods that do not draw current directly from the supply can be used like the meters designed with the balanced-bridge circuit. The internal circuits can therefore be freely combined with the exterior circuits.

Figure 3 Current-voltage methods that do not draw current directly from the power supply

Figure 4 Current-voltage methods that draw current directly from the power supply

2.4 Measurement methods with current from the supply

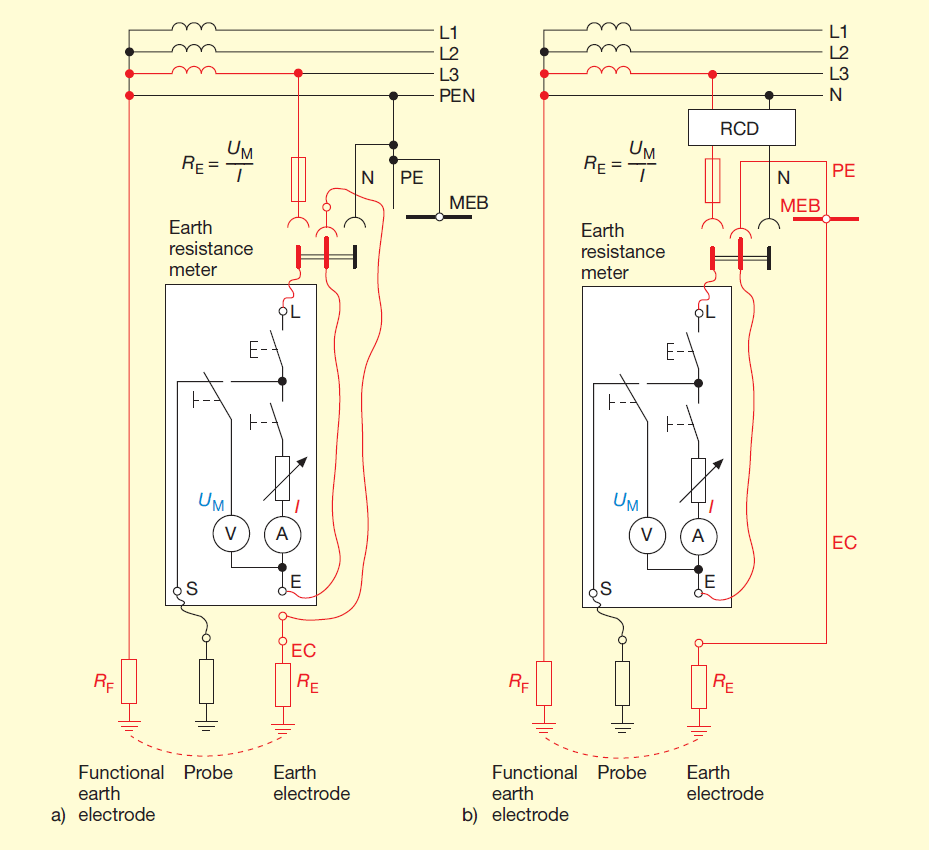

These methods can only be used in networks with a direct connection to earth. As shown in figure 4, the measurement involves drawing the test current from the phase conductor of the supply system. The meters used in this type of measurement are primarily designed for testing electrical safety systems involving residual current devices. The meters are generally connected to the supply via a flexible power lead and an earthed safety plug.

3 Current-Voltage Method that Draws No Supply Current

3.1 Earth resistance meters

The four connection sockets are labelled as shown in figure 5. Sockets for the supply current path and for current measurement:

The frequency of the AC supply PSAC is at least 5 Hz above or below the frequencies 16.7 Hz and 50 Hz and any integer multiples thereof. Typically, the supply frequency is in the range 41–140 Hz, though in some meters a higher frequency is used. Some earth resistance meters also offer the option of selecting the frequency. A number of meters with automatic frequency control (AFC) automatically switch to that frequency offering the lowest level of interference.

To protect against electric shocks, the open-circuit test voltage generated by the meter must not exceed 50 V (r.m.s.) and 70 V (peak). In the case of earth resistance meters used on agricultural sites, these values must be halved. Alternatively, the short-circuit current must not exceed 3.5 mA r.m.s. and a peak value of 5 mA (see [5], sec. 4.5). If neither of these conditions are met, the meter must switch off automatically.

The meter is powered either by a battery, a group of primary cells or a hand-driven generator, though the latter method is now rare. The meter must indicate whether the end-point voltage of the power supply is sufficient to maintain proper instrument function (see [4], sec. 4.3).

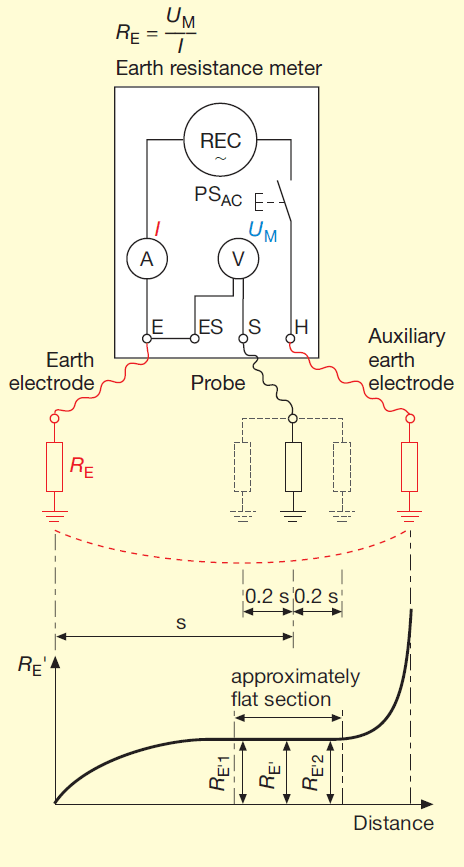

When earth resistance is measured by a method that does not involve current being drawn directly from the supply, the earth resistance RE is computed as the quotient of the measured voltage UM that appears across the earth electrode (and across the meter sockets ES and S) and the measured current I (that flows through sockets E and H). Figure 5 only indicates the basic principle of the complex circuitry within the meter. Usually, the voltage UM and current I are not shown separately and the meter only displays a digital reading of the earth resistance RE. If the AC supply source is a constant-current generator, there is no need to measure the current and calculate the quotient. In this case a voltage meter can be calibrated to display the earth resistance directly.

Most meters are equipped with a switch for selecting the type of measuring circuit, the measurement frequency and/or the measurement range, and for switching the power on and off. Most meters also have a button that is used to initiate measurement. The earth resistance meter must also indicate that the resistance of the auxiliary earth electrode and the probe are within the specified limits (see [5], sec. 4.4). However, it is not advisable to rely too heavily on a warning signal, because by the time a warning signal has been issued, the limit may have been exceeded by a significant amount. User-friendly devices offer additional functions such as:

Figure 5 Current-voltage methods that do not draw current directly from the power supply and that use a probe and an auxiliary earth electrode

I test current; RE earth resistance being measured; RE´ measured earth resistance; UM test voltage

3.2 Methods Using a Probe and An Auxiliary Earth Electrode

3.2.1 Principle

As shown in figure OE, the earth electrode under test, an auxiliary earth electrode and the probe are connected to the earth resistance meter. The test current I flows through the earth electrode, the soil and the auxiliary earth electrode. The voltage UM that appears across the earth resistance RE also appears across the meter sockets ES and S. The earth resistance is displayed as the value of UM divided by I.

3.2.2 Earth electrode (test object)

If socket E is connected to the beginning of the earthing conductor (at the main earthing terminal), the earthing conductor will be included in the measurement of the earth resistance. If, on the other hand, socket E is connected directly to the earth electrode, the resistance of the earthing conductor will not be included in the measurement. The difference, however, is usually slight.

The resistance of the measuring leads will be included in the measurement. This will result in an overestimation of the earth resistance and thus yield a value that errs on the side of safety. To reduce the magnitude of the error, it is expedient to position the earth resistance meter close to the point of connection and to use a short measuring lead. The resistance of the measuring lead can of course be measured and this value subtracted from the value displayed by the earth resistance meter. If the effect of the measuring lead’s resistance is to be avoided at all costs, the jumper linking sockets E and the ES must be removed and each socket connected to the earthing system by its own measuring lead.

The earth electrode under test must not be connected to any other earth electrodes as this would falsify the result of the measurement. In the TN earthing systems found in consumer installations, the earthing conductor must be disconnected from the main earthing busbar as the latter is connected to the PEN conductor of the supply network. This is not required in TT systems as the main earthing busbar is not connected to the neutral conductor of the power supply network. If, nevertheless, the earthing conductor is disconnected, the entire system must be de-energized beforehand and locked out to prevent it being switched on again.

3.2.3 Auxiliary electrode1)

The auxiliary earth electrode should be positioned as far away as possible from the earth electrode under test, so as to minimize the degree of overlap between the potential gradient areas (‘spheres of influence’) surrounding the two electrodes. The larger the electrodes, the farther apart they must be. As a rough guide, the minimum distance apart can be taken to be three times the depth of a rod earth electrode or the average diameter of a ring earth electrode. The figure of 40 m that is found in the documentation provided by some manufacturers can only be considered to be a rough average value. Whether the chosen distance is appropriate will be shown when the correct alignment and positioning of the electrodes is carried out (see sec. 3.2.4).

The greater the resistivity of the soil, the longer the auxiliary electrode needs to be and the deeper it needs to be driven into the ground. If the resistance of the auxiliary earth electrode is too large, measurement errors can arise, because, for example, the constant current normally generated by the AC supply cannot then flow. In such cases, it can prove useful to saturate the area of ground being used for the measurement with water.

3.2.4 Probe2)

As the internal resistance of the voltage measurement path is very large, the resistance of the probe and therefore the size of the probe is of minor importance. The preferred location of the probe is on the straight line between the earth electrode and the auxiliary earth electrode at a position where it has minimum interaction with the spheres of influence of the two electrodes (see diagram in figure 5).

If one were to carry out a series of measurements with different distances between the earth electrode and the probe the results would form a curve whose ends are relatively steep while the intermediate section of the curve is flatter. If the distance between the earth electrode and the auxiliary electrode is large enough, the curve will have an approximately horizontal central section in which the measured resistance to earth is essentially independent of electrode separation.

This central section must be determined by at least three measurements. The midpoint of the central section is not midway between the earth electrode and the auxiliary earth electrode, but lies closer to the auxiliary earth electrode as the spatial extent of the spheres of influence associated with the two earth electrodes differ. In general, the optimum separation between the earth electrode and the probe is about two thirds of the distance between the earth electrode and the auxiliary earth electrode3).

3.2.5 Limitations of method

If no portion of the resistance vs. distance curve is approximately horizontal, then the distance between the earth electrode under test and the auxiliary earth electrode is too small. If the curve exhibits an unusual profile, buried metal installations (e. g. water pipes) are very probably influencing the measurement. In such conditions it is not possible to achieve usable results from the measurement. Measurement may be possible if the electrodes can be laid out perpendicular to their original direction or perpendicular to the longitudinal axis of the buried metal installation or so that they run away from and not above the buried metal installation.

It is also not possible to achieve reliable results if the earth electrode under test is surrounded by other earth electrodes, for example in areas with a high density of buildings. Furthermore measurement is impossible whenever the auxiliary earth electrode and the probe cannot be positioned in the right locations. In all such cases, another measurement technique must be selected.

1) In some publications the auxiliary electrode is also referred to as the outer test electrode, or current test stake.

2) In some publications the probe is also referred to as the inner test electrode, or voltage test stake.

3) Some manufacturers state that the distance between the earth electrode and the probe should be half the distance between the earth electrode and the auxiliary earth electrode. That is incorrect. Other companies recommend placing the probe at a distance from the earth electrode that is always 62 % of the separation between the earth and the auxiliary earth electrode. This method is thus sometimes referred to as the 62 % method. The 62 % mark generally gives a good approximation of the correct location. But the optimum position must always be determined by moving the probe to neighbouring positions.

3.3 Method Using a Probe But No Auxiliary Earth Electrode

3.3.1 Principle

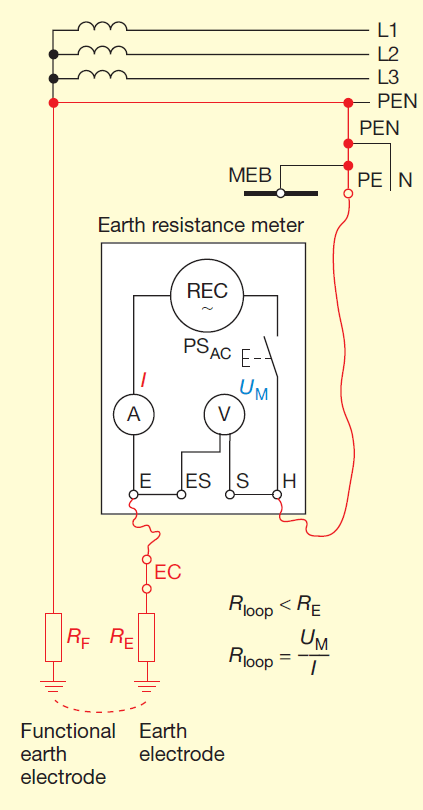

As shown in figure 6, the functional earth of the supply network acts as a replacement for the auxiliary earth electrode. It is extremely important to ensure that the connection is not accidentally made to one of the phase conductors.

In a TN system, the H socket of the meter has to be connected (for instance, via the earthing contact of a plug) to the protective earth (PE) conductor, which itself has been branched off the PEN conductor. The meter socket E is connected to the earthing conductor, which has to be disconnected from the main earthing busbar. Supply networks configured with the TT earthing system have a neutral conductor instead of the PEN conductor. This has to be treated as a live conductor even though it is connected to a functional earth. Applying this method of measuring earth resistance to a TT system would therefore involve connecting the earth resistance meter to the neutral conductor. The method is therefore not approved for use with TT systems.

Figure 6 Current-voltage methods that do not draw current directly from the power supply and that use a probe but no auxiliary earth electrode

EC earthing conductor; MEB main earthing busbar; RB resistance to earth of the functional earth electrode

3.3.2 Problems in the TN system

The method does not function in a TN system if the electrode being measured is strongly coupled or if it is connected via a metal conductor to another earth electrode that itself is connected to the PEN conductor. This would result in the test current flowing in the wrong path so that the display on the earth resistance meter would be smaller than the true value of the resistance to earth. This is discussed in more detail in section 3.4.2.

3.4 Method Without a Probe and an Auxiliary Earth Electrode (‘Stakeless Method’)

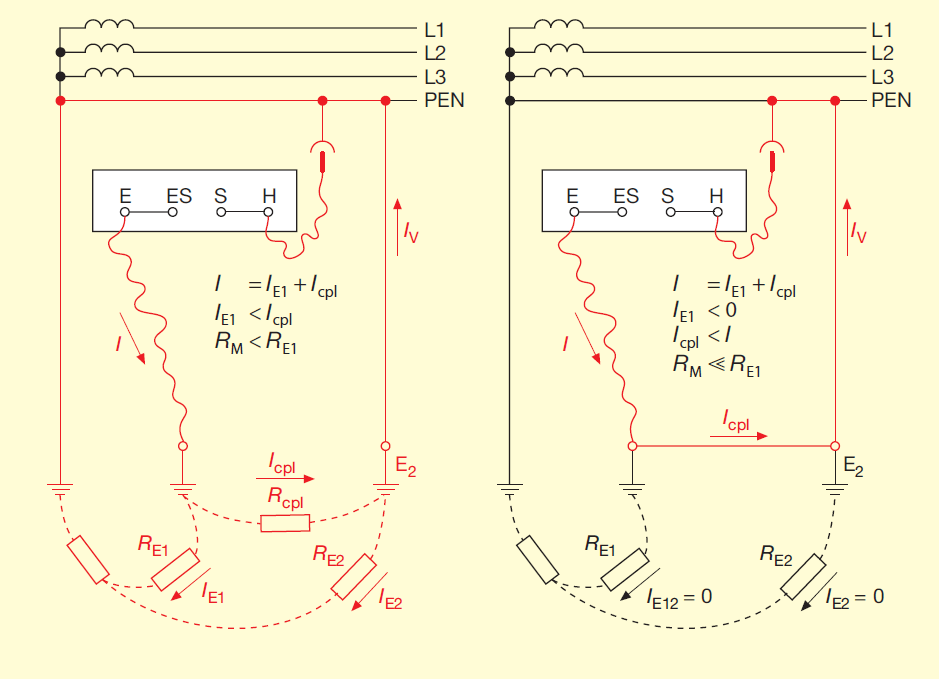

3.4.1 Principle

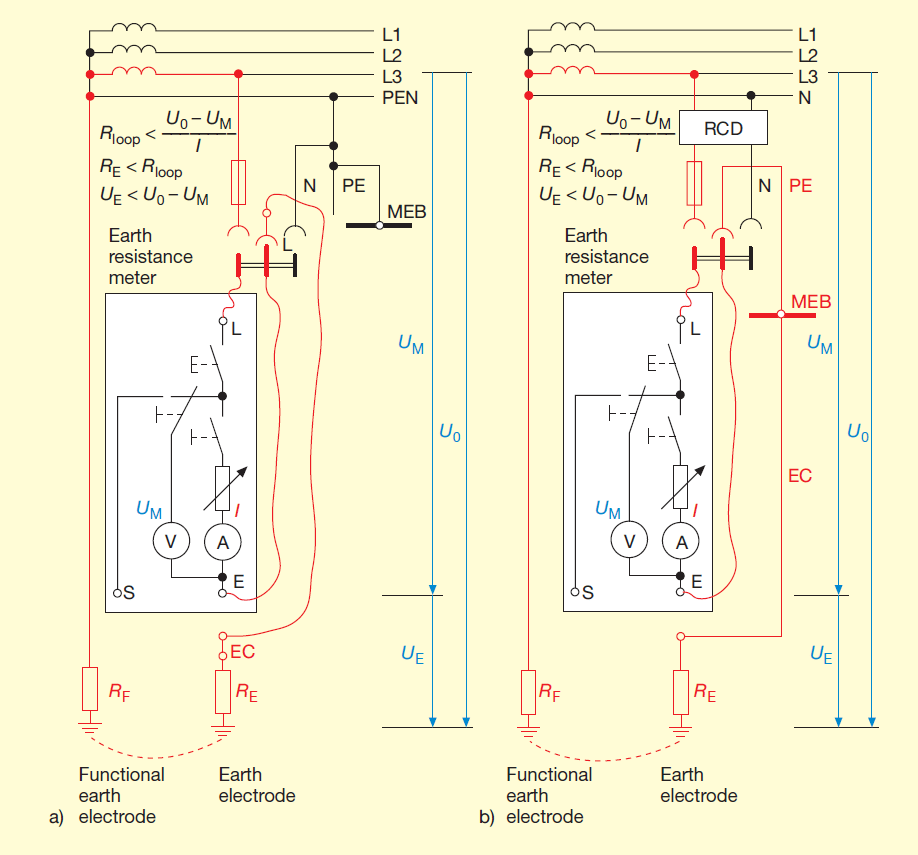

This method (illustrated in figure 7) is an earth-loop resistance measurement because it involves measuring the resistance of a conductor loop via an earth return path. The S and H sockets of the earth resistance meter are connected together. The advantage of this method is that neither an auxiliary earth electrode nor a probe need to be used.

In a TN system the earthing conductor (EC) is disconnected from the main earthing busbar (MEB) and the earth resistance meter is inserted between them. This method is not suitable for measurements on a consumer installations with a TT earthing system.

The resistance measurement displayed on the meter includes the resistance to earth of the functional earth and the resistance of the PEN conductor. If they were accurately known, these values could be subtracted from the resistance displayed on the meter. However, they are difficult to determine, because the functional earth in a TN system comprises not only the functional earth electrode shown in figure 7, it is also connected to numerous earths in the consumer installations of neighbouring buildings. The error that is introduced by measuring these additional resistances results in an overestimation of the earth resistance, yielding a value that errs on the side of safety.

Figure 7 Current-voltage methods that do not draw current directly from the power supply and that use neither a probe nor an auxiliary earth electrode (resistance of conductor loop via earth return path) Rloop loop resistance.

3.4.2 Problems in TN systems

The problem mentioned earlier in section 3.3.2 can also arise when measuring earth resistance without an auxiliary earth electrode and without a probe. Some examples of configurations where problems can arise are shown in figure 8.

Temporary remedial measures include:

Figure 8 Cases involving a TN system in which the method shown in fig. 7 is not suitable

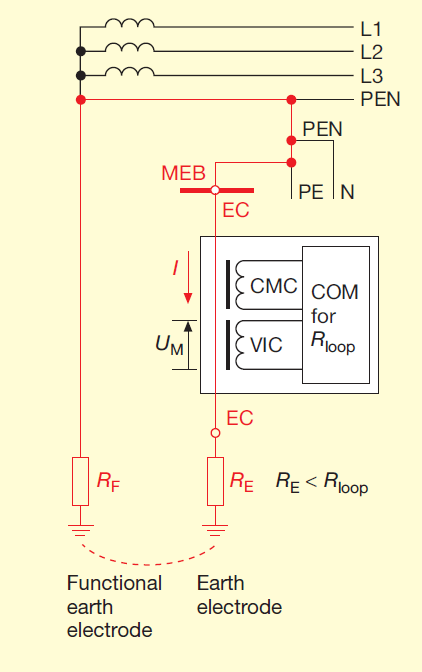

3.5 Stakeless methods (no probe, no auxiliary earth electrode) using a clamp-on ohmmeter

This is a variation on the measurement method described in section 3.4. This technique differs from that shown in figure 7 in that instead of inserting an earth resistance meter into the earthing conductor, a clamp-on ohmmeter (COM) is placed around the earthing conductor (see figure 9). The clamp-on ohmmeter contains both a current-to-voltage transformer (a voltage inducing clamp, VIC) and a current transformer (a current measuring clamp CMC).

Models available include:

The meter displays the resistance calculated as the quotient of the voltage induced by the VIC in the earthing conductor and the resulting test current registered by the CMC. In this case the resistance is the loop resistance Rloop, or more precisely the loop impedance (see section 3.4.1).

Another solution (no separate diagram provided) involves clamping two split-core current transformers around the earthing conductor, one of which functions like the voltage-inducing clamp VIC while the other corresponds to the current measuring clamp CMC that measures the test current. The clamps are connected to a special earth resistance meter (Fluke Earth Ground Tester 1623 or 1625). Depending on which of the Fluke meters is used, either EI-1623 or EI-1625 ‘selective/stakeless clamp set’ is required. The advantage in both cases is that the earthing conductor does not need to be disconnected, making measurement safer and quicker. The problem discussed in section 3.4.2 can also arise in these cases.

If this method is used to make measurements on consumer installations, they must be designed with a TN earthing system. The method is suitable for measuring the resistance to earth of a pylon in an overhead power transmission line if the clamps can be fitted around the earthing conductor.

Figure 9 Method as in figure – but with a clamp-on ohmmeter rather than an earth resistance meter

EC earthing conductor; VIC voltage-inducing clamp; CMC current measuring clamp; COM clamp-on ohmmeter.

3.6 Selective earth resistance measurements using a probe, an auxiliary earth electrode and a clamp-on ohmmeter

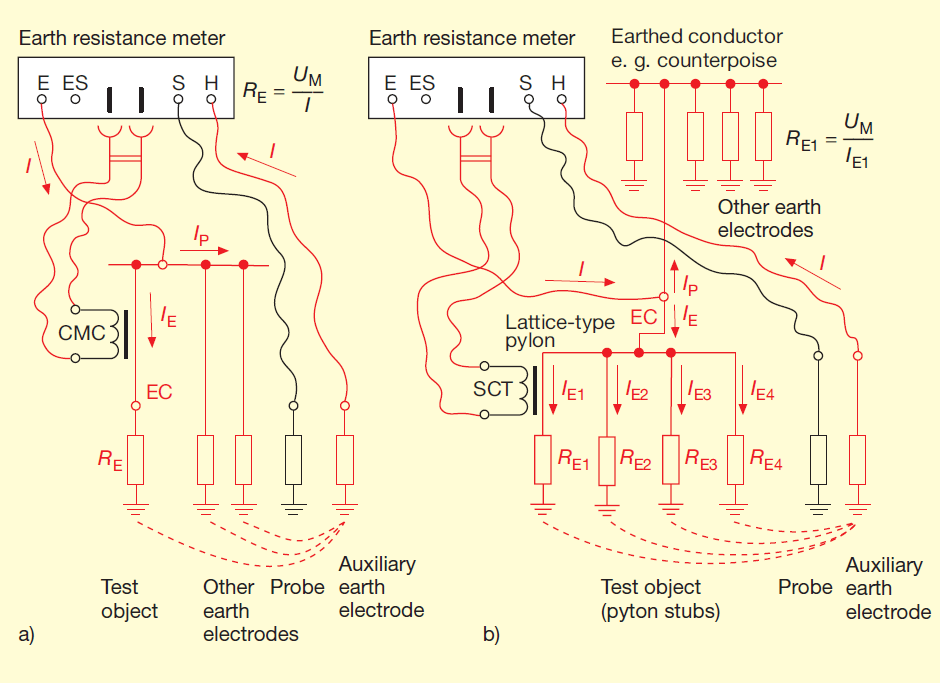

The earth resistance measurement described in this section6) is used if the earth electrode under test cannot or should not be disconnected from other earth electrodes to which it is wired in parallel. This method is based on the technique using a probe and auxiliary earth electrode that is discussed in section 3.2, but in this variant (see figure 10a) a special earth resistance meter (Fluke 1623 or 1625) and an additional clamp-on current transformer (CMC) are required. The current measuring clamp CMC is clamped around the earthing conductor EC connected to the earth electrode under test and connected to a multi-pole socket on the earth resistance meter. When the meter is connected in this way and the rotary selector switch has been set appropriately, IP, the portion of the test current I flowing via the other parallel earth electrodes, has no effect on measurement result so that the branch current IE recorded by current measuring clamp CMC is solely responsible for determining the resistance to earth RE displayed by the meter.

Figure 10b) shows the measurement circuit used when dealing with a steel-lattice electricity pylon that cannot be electrically disconnected from the earthed conductor (e. g. counterpoise, PEN conductor or neutral conductor). As the pylon structure serves as the earthing conductor EC, it is clearly not possible to clamp a CMC around the earthing conductor as in figure 10a). In this case, measurements are made by consecutively clamping a splitcore transformer SCT (Fluke EI-162BN7)) around the four pylon legs that are connected to the four pylon stubs that act as earth electrodes. The earth resistance meter displays the resistances RE1 to RE4 consecutively. The resulting earth resistance RE of the four mast feet, which are connected to one another through the steel lattice structure, can be calculated by equation (5):

Figure 10 Selective earth resistance measurements using a probe, an auxiliary earth

electrode and split-core current transformers

4) Induced voltage: approx. 60 mV; frequency: 2403 Hz; inner diameter of clamp jaw: 32 mm. Data provided without warranty.

5) Induced voltage: approx. 30 mV; frequency: 1667 Hz; inner diameter of clamp jaw: 23 mm. Data provided without warranty.

6) On its own, the expression ‘selective earth measurement’ is ambiguous, as other earth resistance measurement techniques are also selective, e.g. those presented in sections 3.4, 3.5 and 4.6.

4 Measurement Methods That Draw Current From Supply

4.1 Measuring equipment

The meters used for this type of measurement are designed primarily for testing electrical safety systems that make use of residual current devices. To ensure the simplest and safest connection to the power supply, the meters are typically equipped with a flexible power cable and an earthed safety plug. The meters also have a socket S for the probe (see figures 11 and 13). The socket E is used to connect the meter to the earth electrode under test unless one of the cores (protective earth core) of the flexible power cable and the earth contacts on the plug are used for this purpose. As the test meters are classified as Class II equipment (see ref. [4], sec. 4.5), the core and the plug’s earth contact do not serve as protection against shock hazards.

The meters do not have their own power source unless this is needed for some other type of measurement. Some meters may have an additional connector socket for a current measuring clamp.

7) The jaws of the split-core transformer are dimensioned for large rectangular-section conductors such as the legs of high-voltage pylon

Figures 11 to 14 show the basic principles of the complicated circuitry inside these meters. In most of these meters, the actual measurement process (including any gradual increase in the test current that may be involved) is carried out automatically. Rather than displaying the measured voltage and current separately, the resistance to earth is computed and displayed digitally on the meter.

A selector switch enables the type of measurement, measurement technique, measurement circuit, parameter range and/or measurement sequence to be chosen. Most meters are fitted with a ‘START’ button to initiate the measurement process. User-friendly devices offer additional functions such as:

To provide protection against electric shock, the meter must switch off automatically as soon as it causes a fault voltage greater than 50 V in the earthing system being measured. If a variable resistor is used to increase the test current, the current must not exceed 3.5 mA at the beginning of the measurement (see ref. [6], sec. 4.7). Measurements in which the test current is increased gradually and measurements in which the current is only allowed to flow at maximum strength for a short period are both common.

The difficulty associated with drawing current directly from the power supply is that the measurement is made at the supply frequency and interference currents that originate in the power supply or that are carried via earth can easily introduce measurement errors. The larger the test current, the less effect these sources of interference will have. It is therefore expedient to work with a large test current. However, a large test current can itself be problematic when the meter is connected behind a residual current device, as it can cause the RCD to trigger. This can be avoided by using one of the following procedures:

Whenever interference effects may play a role, several measurements should be conducted and the results compared with one another.

Figure 11 Current-voltage methods that draw current directly from the power supply and

that use a probe

Figure 12 Current-voltage methods that draw current directly from the power supply and

that use the PEN or neutral conductor instead of a probe

Figure 13 Current-voltage methods that draw current directly from the power supply and

that do not use a probe

Figure 14 Selective earth resistance measurement methods that draw current directly from

the power supply and that use a probe and a clamp-on ammeter

4.2 Connections to power supply and earth electrode

The meter is typically connected to the power supply via its earthed safety plug. If the plug is inserted incorrectly, no hazard arises but no measurement is possible. Although not shown in the figures, the internal circuitry of most of the meters only functions if the meter is connected to the phase conductor and to the neutral conductor.

The test current can induce accidental triggering of an upstream RCD. This may need to be taken into account when connecting the meter (see discussion in section 4.1 above). Depending on the type of meter used, the earth electrode to be measured is

Connections between the earth electrode under test and other earth electrodes would yield erroneous results. It is for this reason that when measurements are made on consumer installations with a TN earthing system, the earthing conductor EC has to be separated from the main earthing busbar MEB (see figures 11a) to 14a)) as the latter is connected via the PEN conductor of the service cable and the supply network to other earth electrodes. Disconnection is not required in a TT system as the main earthing busbar is not linked to the neutral line of the supply network and the connection can be made as shown in figures 11b) to 14b).

4.3 Methods using a probe

This method is the most accurate of the techniques that draw current directly from the supply provided that the probe can be inserted into the soil at a suitable location. A schematic of the measurement set-up is shown in figure 11. The probe has to be located so that it is outside the sphere of influence of the earth electrode. The voltage UM between the sockets E and S generates the test current I in the earth electrode.

4.4 Method using the PEN conductor or neutral conductor instead of a probe

This measuring techniques can be used whenever it is not possible to insert a probe into the ground at the right location. In this method (see figure 12 ) the probe is replaced by connecting socket S of the meter to the PEN or PE conductor in a TN system or to the neutral conductor in a TT system. Caution! The neutral conductor must be treated as if it is live, even though it is earthed.

The value displayed by the meter includes the resistance to earth of the functional earth electrode. This will overestimate the resistance of the earth electrode and thus yield a value that errs on the side of safety.

The voltages generated by operating currents and by fault currents in the functional earth or in the PEN conductor or neutral conductor of the power supply system can result in erroneous measurement results. The accuracy of this technique is therefore lower than that achievable using the method described in section 4.3.

4.5 Method without a probe

This method (illustrated schematically in figure 11) involves measuring the resistance of a conductor loop via an earth return path. In this method, the voltage across the test object (UE) is not measured directly. It is determined as the difference between the potential drop between the phase conductor and earth when the test resistance is switched off (U0) and that when the test current I is flowing (UM). The resistance value measured includes the resistances of the functional earth, the transformer and the phase conductor. This will result in an overestimation of the earth resistance and thus yield a value that errs on the side of safety.

This method is particularly attractive as it can be performed with a minimum of effort. But it suffers from the weakness that supply load fluctuations that happen to occur simultaneously while the measurement is being made will cause significant additional measurement errors. To limit these errors, it is therefore expedient to work with a large test current. It is also advisable to perform numerous measurements, to reject any extreme values recorded and to compute the mean value from the remaining measurement data.

4.6 Selective earth resistance measurements using a probe and a clamp-on ammeter

The method selective earth resistance measurement8) is used if, for the purposes of the measurement, the earth electrode under test cannot or should not be disconnected from other earth electrodes to which it is wired in parallel. It is based on the method using a probe discussed in section 4.3, but in this variant (see figure 14) a special earth resistance meter (Chauvin Arnoux C.A. 6115N or C.A. 6456) and an additional current measuring clamp CMC are required. The current measuring clamp is connected to a multipole socket on the meter and the clamp jaws are placed around the earthing conductor EC connected to the earth electrode under test.

If the meter is connected in this way and if the rotary selector switch set appropriately, IP, the portion of the measuring current I flowing via the other parallel earth electrodes, has no effect on measurement result so that the branch current IE recorded by the current measuring clamp CMC is solely responsible for determining the resistance to earth RE displayed by the meter.

8) On its own, the expression ‘selective earth measurement’ is ambiguous, as other earth resistance measurement techniques are also selective, e. g. those presented in sections 3.4, 3.5 and 3.6.

References

[1] IEC 60364-4-41:205 Erection of power installations with nominal voltages up to 1000 V – Part 4-41: Protection for safety – Protection against electric shock.

[2] Hering, E.: Schutzerder des TT-Systems (engl.: Protective earthing in the TT system). Elektropraktiker, Berlin 59 (2005) 5, p. 370-373.

[3] IEC 60364-6:2006-02 Low-voltage electrical installations – Part 6: Verification.

[4] IEC 61557-1:2007 Equipment for testing, measuring or monitoring of protective measures – Part 1: General requirements.

[5] IEC 61557-5:2007 Equipment for testing, measuring or monitoring of protective measures – Part 5: Resistance to earth.

[6] IEC 61557-6:2007 Equipment for testing, measuring or monitoring of protective measures – Part 6: Effectiveness of residual current devices (RCD) in TT, TN and IT systems.

[7] IEC 61557-10:2000 Equipment for testing, measuring or monitoring of protective measures – Part 10: Combined measuring equipment for testing, measuring or monitoring of protective measures.

[8] Hering, E.: Probleme mit einem der Erdungsmeßverfahren beim TN-System (engl.: Problems with an earth resistance measurement technique in a TN system). Elektropraktiker, Berlin 53 (1999) 9, p. 820-822.

[9] Hering, E.: Durchgangsprüfungen an Erdungsanlagen [Continuity testing in earthing systems]. Elektropraktiker, Berlin 59 (2005) 11, p. 888- 891 und in diesem Sonderdruck.

[10]DIN EN 62305-3 (VDE 0185-305-3):2006-10: Protection against lightning – Part 3: Physical damage to structures and life hazard.

Application Note

Published by H. Markiewicz and A. Klajn, November 2014

ECI Publication No. Cu0120

Document Issue Control Sheet

| Document Title: | Application Note – Earthing Systems: Fundamentals of Calculation and Design |

| Publication No: | Cu0120 |

| Issue: | 03 |

| Release: | June 2003 |

| Author(s): | H. Markiewicz and A. Klajn |

| Reviewer(s): | D. Chapman, S. Fassbiner |

Document History

| Issue | Date | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | June 2003 | Initial publication |

| 2 | November 2011 | Upgrade by David Chapman for adoption into the Good Practice Guide |

| 3 | November 2014 | Review with minor adaptations |

Disclaimer

While this publication has been prepared with care, European Copper Institute and other contributors provide no warranty with regards to the content and shall not be liable for any direct, incidental or consequential damages that may result from the use of the information or the data contained.

SUMMARY

This Application Note discusses the principles of earthing electrode design with particular emphasis on earth potential distribution of various electrode geometries.

The electrical properties of the ground and variations according to type and moisture content are discussed. The equation for calculation of the earthing resistance and potential distribution for an idealized hemispherical earth electrode is derived. The concepts of step and touch voltages are discussed and the effect of earthing electrode geometry shown.

The concepts developed here are the basis for the practical guidance given in the Application Note Earthing Systems: Basic Constructional Aspects.

INTRODUCTION

The concept of modern integrated earthing systems was introduced in the Application Note Integrated Earthing Systems. In an integrated earthing system, all of the different earthing functions – lightning and short circuit protection, safety and electromagnetic compatibility – are designed and implemented as one entity.

This Application Note is concerned only with the part of an integrated system that is buried in the ground, called the earth or ground electrode, and covers fundamental aspects of design and calculation. A further Application Note, Earthing systems: Basic Constructional Aspects gives practical guidance on the design of ground electrodes and the calculation of their properties.

The earthing system is an essential part of power networks at both high- and low-voltage levels. A good earthing system is required for:

In modern practice these functions are provided by a single system designed to fulfill the requirements of all of them. Although some elements of an earthing system may be provided to fulfill a specific purpose, they are nevertheless part of one single system – standards require that all earthing measures within an installation are bonded together, forming one system.

BASIC DEFINITIONS [1, 2]

Earthing or earthing system is the total of all means and measures by which part of an electrical circuit, accessible conductive parts of electrical equipment (exposed conductive parts) or conductive parts in the vicinity of an electrical installation (extraneous conductive parts) are connected to earth.

Earth or ground electrode is a metal conductor, or a system of interconnected metal conductors, or other metal parts acting in the same manner, embedded in the ground and electrically connected to it, or embedded in the concrete, which is in contact with the earth over a large area (e.g. foundation of a building).

Earthing conductor is a conductor which connects a part of an electrical installation, exposed conductive parts or extraneous conductive parts to an earth electrode or which interconnects earth electrodes. The earthing conductor is laid above the soil or, if it is buried in the soil, is insulated from it.

Reference earth is that part of the ground, particularly on the earth surface, located outside the sphere of influence of the considered earth electrode, i.e. between two random points at which there is no perceptible voltages resulting from the earthing current flow through this electrode. The potential of reference earth is always assumed to be zero.

Earthing voltage (earthing potential), VE, is the voltage occurring between the earthing system and reference earth at a given value of the earth current flowing through this earthing system.

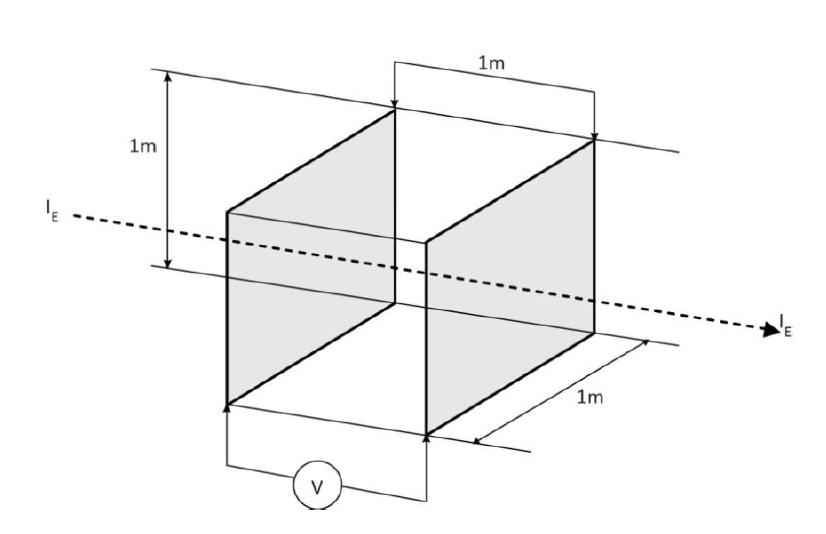

Earth resistivity ρ (specific earth resistance) is the resistance, measured between two opposite faces, of a one-metre cube of earth (See Figure 1). The earth resistivity is expressed in Ωm.

Earth surface potential, Vx, is the voltage between a point x on the earth’s surface and reference earth.

Figure 1 – Diagram illustrating the physical sense of earth resistivity ρ.

ELECTRICAL PROPERTIES OF THE GROUND

The electrical properties of the ground are characterised by the earth resistivity ρ. In spite of the relatively simple definition of ρ given above, the determination of its value is often a complicated task for two main reasons:

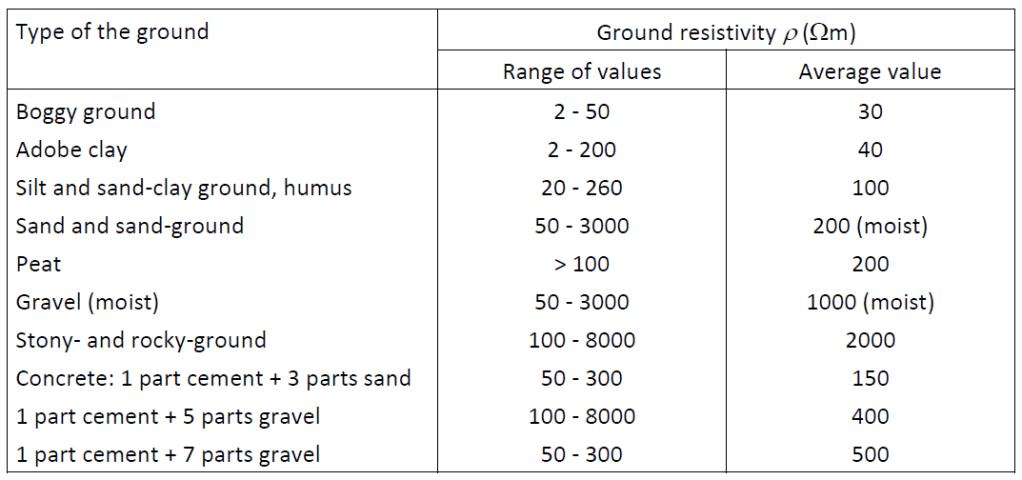

The calculation of the earthing resistance requires a good knowledge of the soil properties, particularly of its resistivity ρ. Thus, the large variation in the value of ρ is a problem. In many practical situations, a homogenous ground structure will be assumed with an average value of ρ, which must be estimated on the basis of soil analysis or by measurement. There are established techniques for measuring earth resistivity. One important point is that the current distribution in the soil layers used during measurement should simulate that for the final installation. Consequently, measurements must always be interpreted carefully. Where no information is available about the value of ρ it is usually assumed ρ = 100 Ωm. However, as Table 1 indicates, the real value can be very different, so acceptance testing of the final installation, together with an assessment of likely variations due to weather conditions and over lifetime, must be undertaken

Table 1 – Ground resistivity ρ for various kinds of the soil and concrete [2, 4].

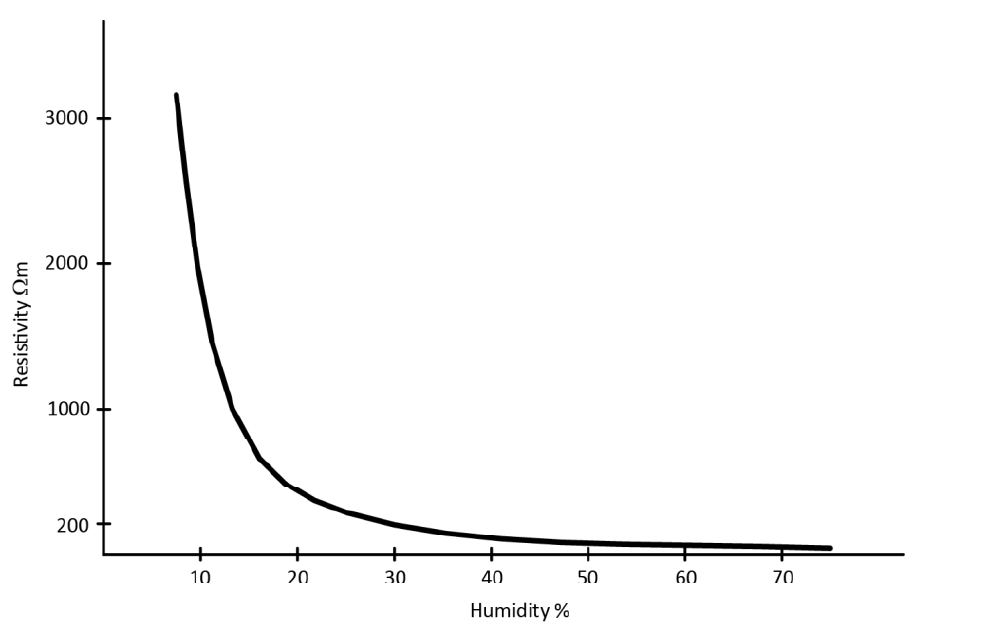

The other problem in determining soil resistivity is the moisture content, which can change over a wide range, depending on geographical location and weather conditions, from a low percentage for desert regions up to about 80 % for swampy regions. The earth resistivity depends significantly on this parameter. Figure 2 illustrates the relationship between resistivity and humidity for clay. One can see here that, for soil humidity values higher than 30 %, changes of ρ are very slow and not significant. However, when the ground is dry, i.e. values lower than 20 %, the resistivity increases very rapidly.

In regions with a temperate climate, for example in European countries, the earthing resistance changes according to the season of the year, due to dependence of soil humidity on earth resistivity. For Europe, this dependence has an approximate sine form, where the maximum value of earthing resistance occurs in February and the minimum value in August. The average value occurs in May and November. The amplitude in February is approximately 30 % larger than average, while in August it is about 30 % smaller than the average [4].

It must be remembered that the effect of freezing is similar to that of drying – the resistivity increases significantly.

For these reasons the calculations of earth resistance and the design of electrodes can only be performed up to a limited level of accuracy.

Figure 2 – Earth resistivity ρ of clay as function of soil humidity.

ELECTRICAL PROPERTIES OF THE EARTHING SYSTEM

The electrical properties of earthing depend essentially on two parameters:

Earthing resistance determines the relation between earth voltage VE and the earth current value. The configuration of the earth electrode determines the potential distribution on the earth surface, which occurs as a result of current flow in the earth. The potential distribution on the earth surface is an important consideration in assessing the degree of protection against electric shock because it determines the touch and step potentials. These questions are discussed briefly below.

The earthing resistance has two components:

The resistance RL is usually much smaller than the dissipation resistance RD. Thus, usually the earthing resistance is estimated to be equal to the dissipation resistance RD. In the literature, ‘earthing resistance’ usually refers to the dissipation resistance.

Any earth connection made available by the supplier appears in parallel with the locally provided earth and may well be expected to have lower impedance at fundamental and harmonic frequencies than the local earth. However, the availability and characteristics of this path are beyond the designer’s control and hence should not be considered in the design of the earthing system which should be adequate for the required purpose in its own right.

EARTHING RESISTANCE AND POTENTIAL DISTRIBUTION

In AC circuits one must consider essentially the impedance of an earthing ZE, which is the impedance between the earthing system and the reference earth at a given operating frequency. The reactance of the earthing system is the reactance of the earthing conductor and of metal parts of the earth electrode. At low frequencies – the supply frequency and associated harmonics – reactance is usually negligible in comparison to earthing resistance, but must be taken into account for high frequencies such as lightning transients. Thus, for low frequencies, it is assumed that the earthing impedance ZE is equal the dissipation resistance RD, which is in turn assumed to be approximately equal to the earthing resistance, R:

The earthing resistance R of an earth electrode depends on the earth resistivity ρ as well as the electrode geometry. In order to achieve low values of R the current density flowing from the electrode metal to the earth should be low, i.e. the volume of earth through which the current flows should be as large as possible. Once the current flows from metal to earth it spreads out, reducing current density. If the electrode is physically small, e.g., a point, this effect is large, but is very much reduced for a plate where spreading is only effective at the edges. This means that rod, pipe, or wire electrodes have a much lower dissipation resistance than, for example, a plate electrode with the same surface area. Moreover, it is well documented in the literature that dc- and ac-induced corrosion increases with current density. Low current density extends electrode life.

The calculation of earthing resistance is usually performed under the assumptions that the ground is boundless and of uniform structure with a given value of resistivity. It is possible to determine exact equations for earthing resistance but, in practice, their usefulness is very limited, especially in case of complex and meshed earth electrodes where the mathematical relations become very complicated. Furthermore, even a small inaccuracy in value of the resistivity has a significant influence on the actual earthing resistance of meshed earth electrodes and it is often very difficult to determine the earth resistivity with the accuracy required. Because of this, exact theoretical equations of earthing resistance are usually used only for simple structures of earth electrodes in order to illustrate the relationship between the earth voltage, earth potential distribution and the earth current. For extended and meshed earth electrodes, approximations of earth resistance are used.

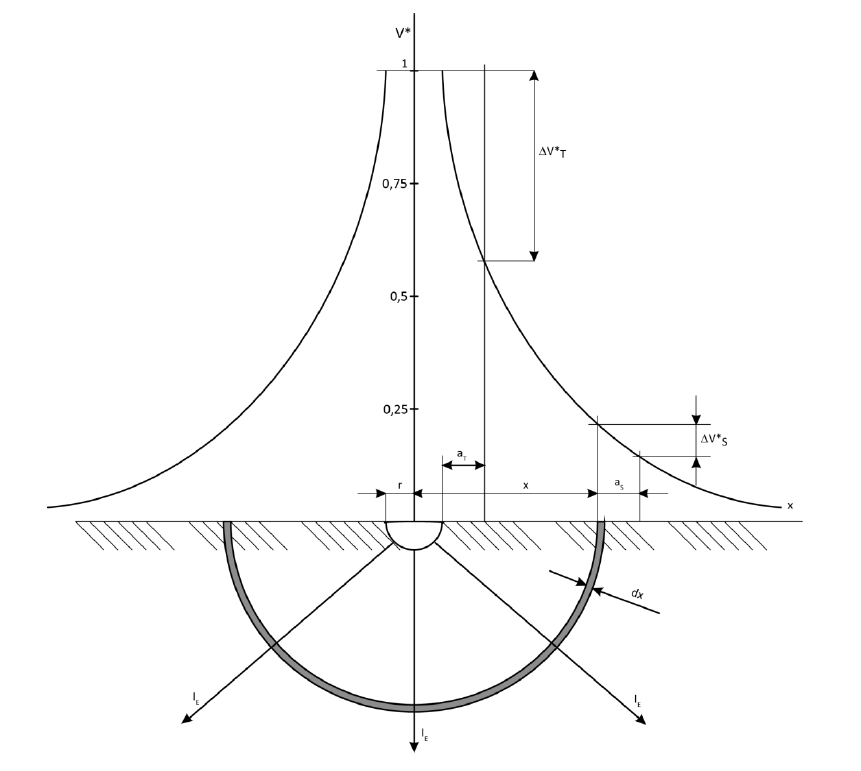

A basic model of the earth electrode configuration, used for illustrating the fundamental electrical properties, is a hemisphere embedded in the ground surface (Figure 3).

Figure 3 – Illustration of a notional hemispherical earth electrode, showing parameters required to calculate the earthing resistance and potential distribution on the ground surface (with ρ = const):

The earth current flowing to such an electrode is assumed to flow radially to the earth. The surface of the hemisphere, as well as all hemisphere cross sections, dx, of the ground, are assumed to be equipotential, and the current lines are therefore perpendicular to these surfaces. Under these conditions the resistance of the hemisphere-ground-sheath of thickness dx and the radius x is expressed as follows (with ρ assumed constant):

The resistance of the hemisphere-earth electrode is given by:

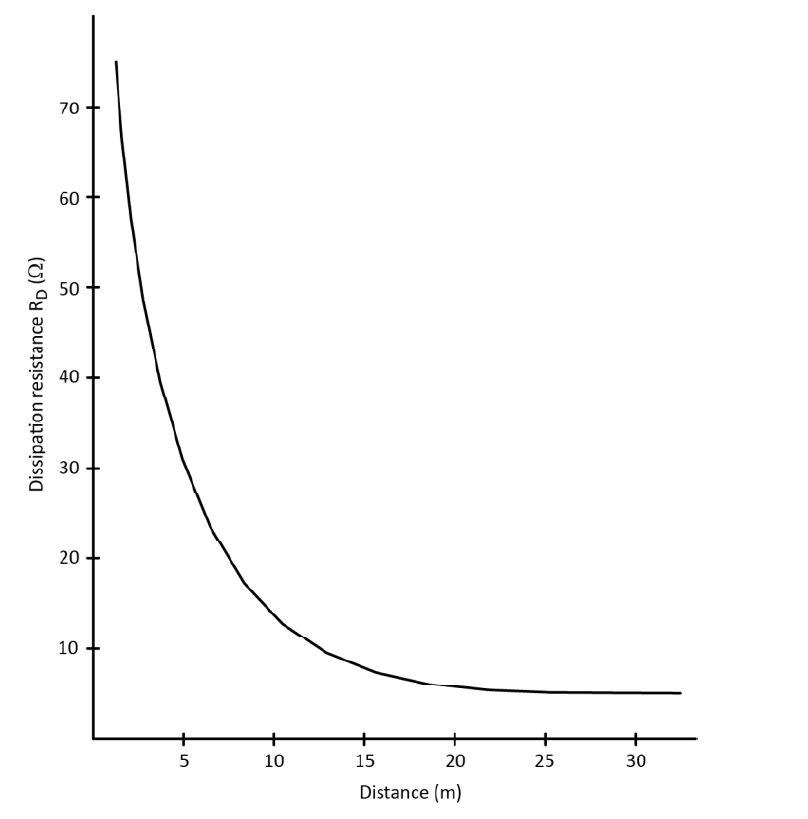

The earth resistance depends significantly on how deep the electrode is sunk in the ground. This is because the moisture content is higher and more stable for deeper ground layers than for shallow layers. Layers near the surface are influenced more by seasonal and short-term weather variations and are subject to freezing. This problem is illustrated in Figure 4, for a vertical rod earth electrode, where one can see the considerable reduction of earthing resistance as the depth of penetration of a rod electrode increases. However, it is not always possible to place electrodes at the preferred depth for geological reasons, for example, where there are rocks or obstructions close to the surface or where the electrode system covers a large area.

Figure 4 – Example of dissipation resistance of a vertical rod earth electrode as a function of the depth d.

One can distinguish the following types of earth electrodes:

The first four arrangements are surface earth electrodes, which usually consist of strip wire or band arranged as radial, ring or meshed electrodes, or a combination of these embedded at shallow depths of up to about 1 m. An important advantage of these constructions is the favourable surface potential distribution. Rod electrodes belong to so called deep earth electrodes, the advantage of these is that they pass through soil layers of different conductivity and are particularly useful in places where the shallow layers have poor conductivity. In this way it is easy to obtain an expected electrode resistance (Figure 4). Another advantage of rod electrodes is that they can be installed in places where there is a limited surface area available to install the electrode. However, surface potential distribution of rod electrodes is unfavourable, so in practice a combination of rod and surface earth electrodes are also used, in order to obtain both a good resistance and desirable surface potential distribution. Surface potential distribution is subject of the next section.

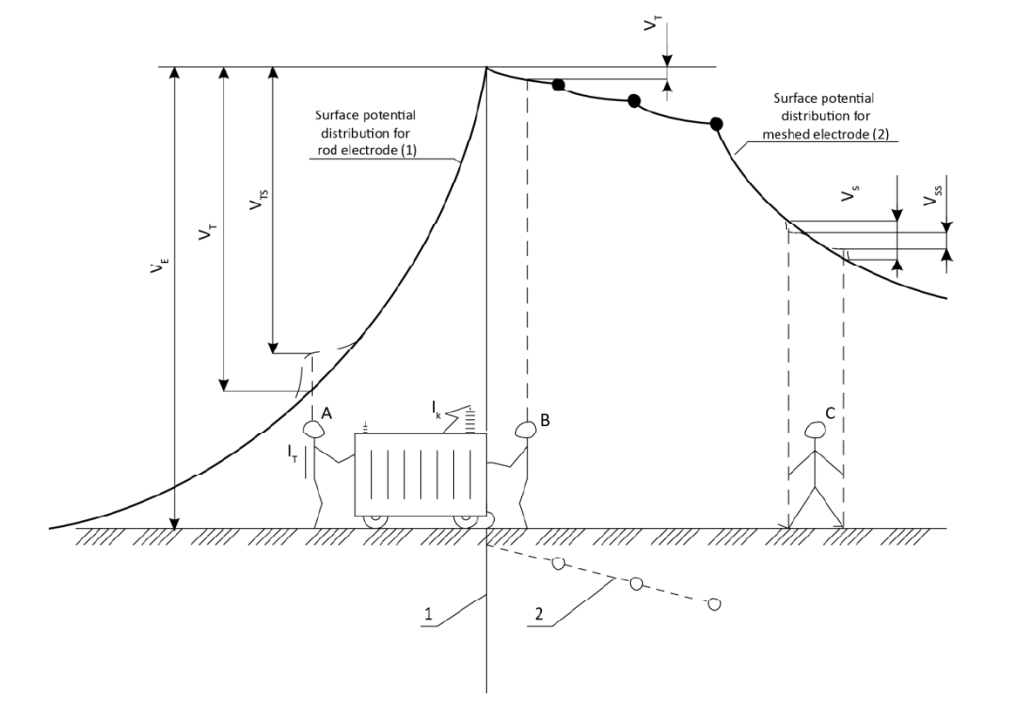

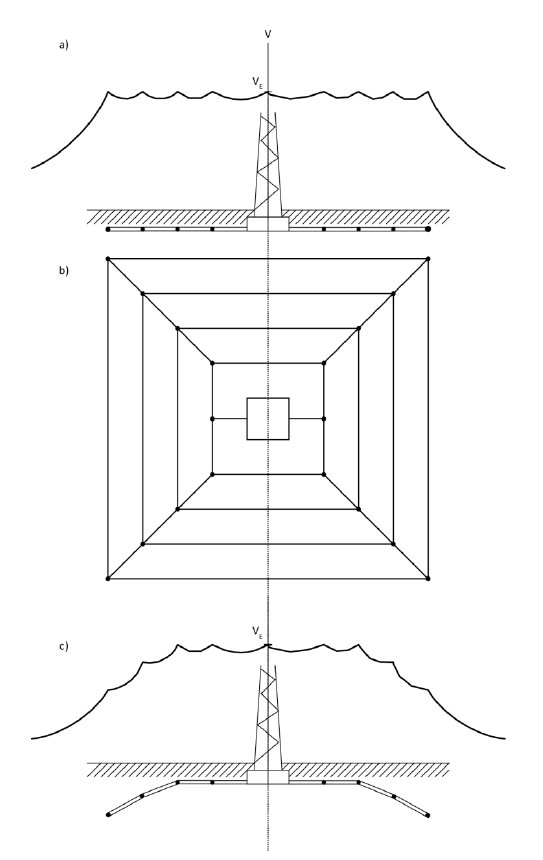

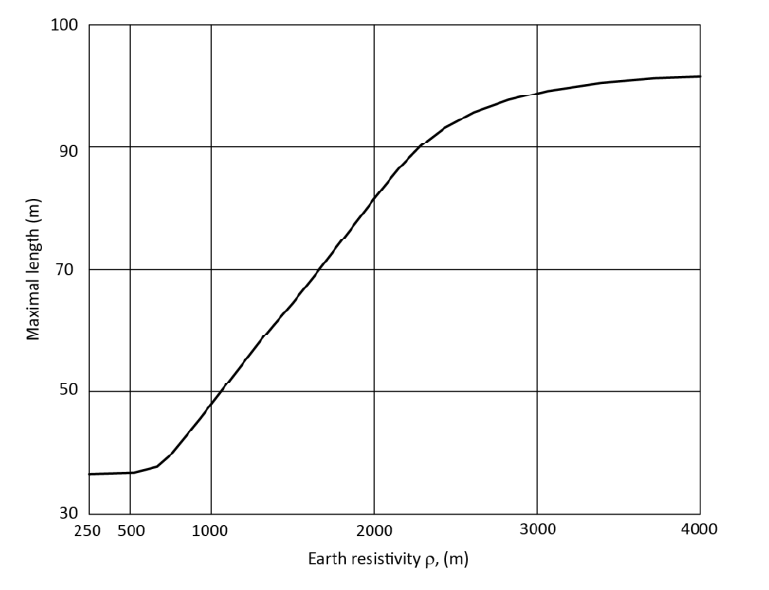

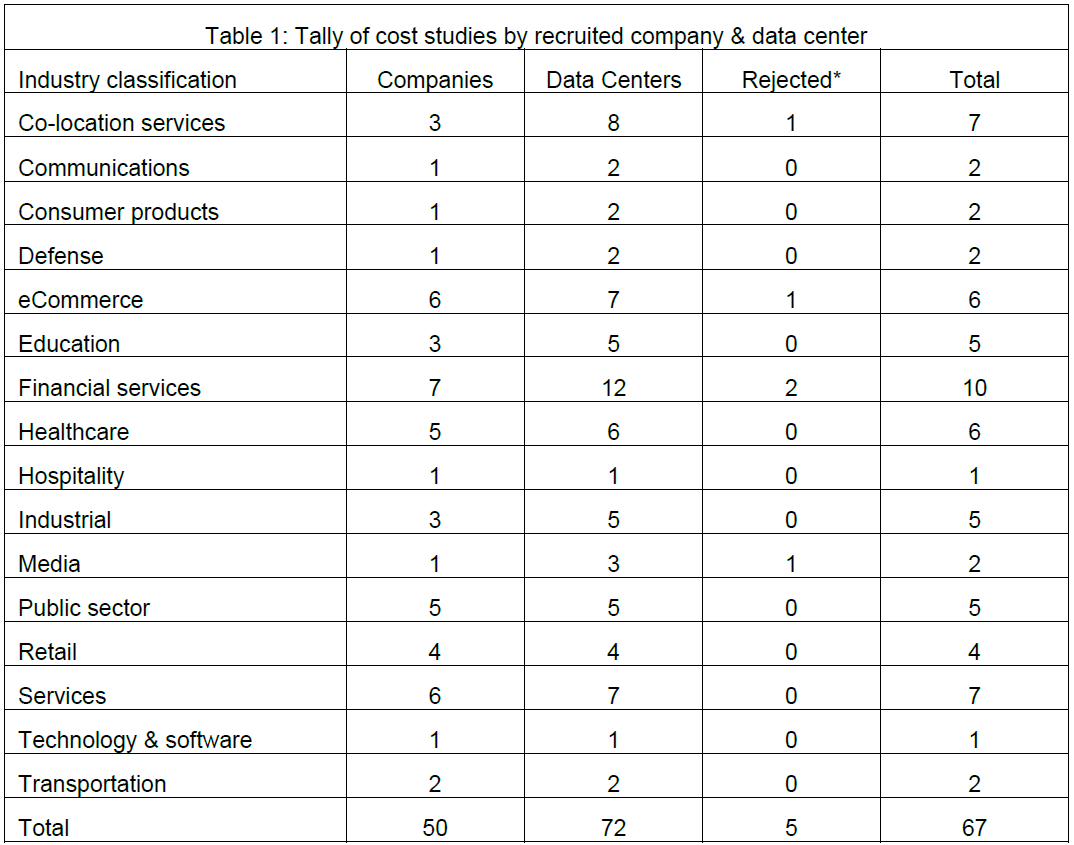

More detailed descriptions and basic equations concerning earth resistance of typical earth electrodes mentioned are given in the Application Note Earthing systems – Basic Constructional Aspects.