Published by Mark McGranaghan, VP, Integrated Grid, Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), August 2020

Email: mmcgranaghan@epri.com

Published by Mark McGranaghan, VP, Integrated Grid, Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), August 2020

Email: mmcgranaghan@epri.com

Published by Daniel Sabin, Electrotek Concepts , USA and Math Bollen, Luleå University of Technology, Sweden

Emails: d.sabin@ieee.org & m.bollen@ieee.org

Published in 23rd International Conference on Electricity Distribution, Lyon, 15th-18th June, 2015

ABSTRACT

IEEE Std 1564-2014 Guide for Voltage Sag Indices is a new standard that identifies appropriate voltage sag indices and characteristics of electrical power and supply systems as well as the methods for their calculation. This paper presents an overview of IEEE Std. 1564-2014. It summarizes the IEEE 1564 methods for quantifying the severity of individual voltage sag events, for quantifying the performance at a specific location via single-site indices, and for quantifying the system performance via system indices. The methods are appropriate for use in transmission, distribution, and utilization electric power systems.

IEEE Std 1564-2014 Guide for Voltage Sag Indices was developed by the Power Quality Subcommittee of the IEEE Power & Energy Society [1]. Draft 19 of IEEE P1564 was successfully balloted in November 2013, and was approved as a new standard by IEEE Review Committee (RevCom) on 27 March 2014. IEEE 1564 provides methods for computing voltage sag indices and characteristics. Voltage sag indices are one way of quantifying the performance of electric power and supply systems. A voltage sag is a short duration rms voltage variation associated with a reduction in voltage that may cause disruption of the operation of certain types of equipment. Voltage sags are due to short-duration increases in current, typically due to faults, motor starting, transformer energizing, or feeder energizing. Voltage sag events can occur at any location in the power system with a frequency of occurrence between several times per year to hundreds of times per year.

IEEE 1564 provides equivalent methods for computing indices and characteristics concerning voltage swells. A voltage swell is a short-duration increase in voltage. On multiphase systems, a voltage swell on one phase can be associated with a voltage sag on another phase. Some of the methods discussed will classify such an event as both a voltage sag and a voltage swell.

Methods are presented for quantifying the severity of individual rms variation events, for quantifying the performance at a specific location (i.e., single-site indices), and for quantifying the performance of the whole system (i.e., system indices). Different methods are presented for each. This guide does not recommend the use of a specific set of indices, but instead presents guidelines for the method for calculating specific indices when such an index is used. The large variation in customers sensitive to voltage sags and network companies supplying them makes it difficult to prescribe a specific set of indices. Instead, this guide aims at assisting in the choice of index and ensuring reproducibility of the results.

To give a value to the performance of a power system in terms of voltage sags, the guide presents a five-step procedure:

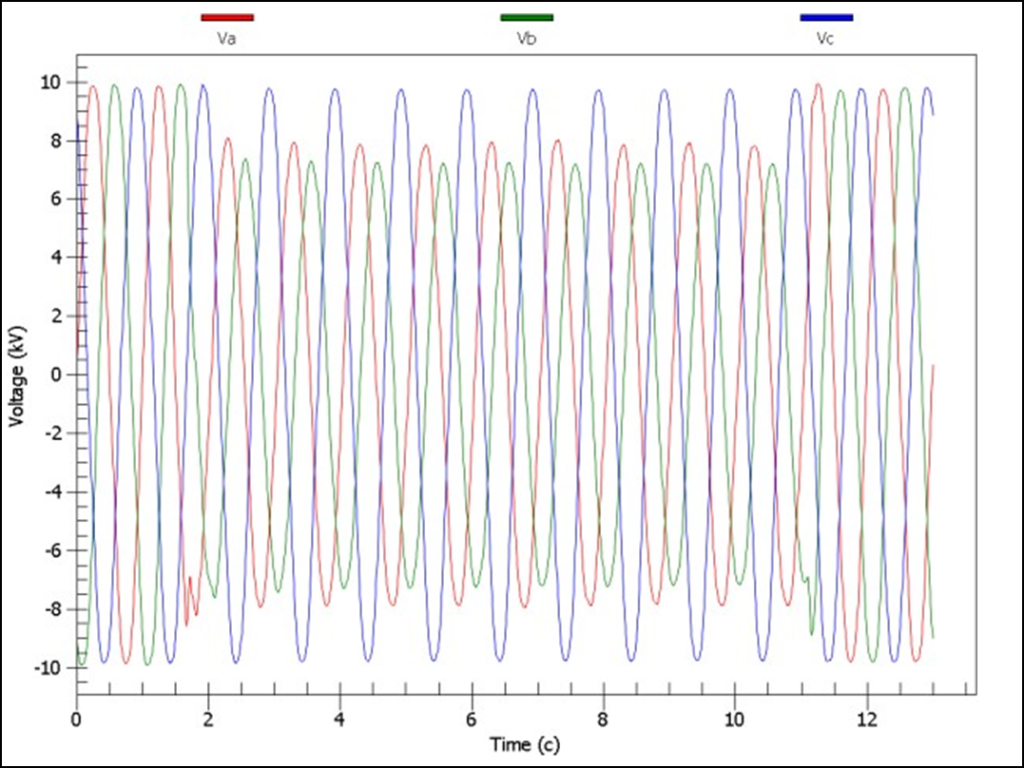

The guidelines in IEEE 1564 advocate computing one or more characteristics from the sampled voltages. From the sampled waveforms in the three phases, such as in Figure 1, one or three voltage magnitudes as a function of time are obtained. For single-channel measurements and multi-channel measurements, the rms voltage is computed over one cycle and is updated every half cycle. This quantity is defined in IEC 61000-4-30 [2] as Vrms(1/2). For three-phase measurements, either the minimum Vrms(1/2) is used to characterize the event, or the “characteristic voltage” is used. These time functions are used to determine the single-event indices retained voltage (“sag magnitude”), depth, and duration [2].

In addition to the two-index method (retained voltage or depth and duration), two single-index methods are introduced in IEEE 1564: the voltage sag energy and the voltage sag severity. In both cases, the severity of each event is quantified by one single value.

From the sampled voltages one or more characteristics as a function of time are calculated for every recording. This function is used to determine the retained voltage and the duration of the event. The rms voltage is calculated over a one-cycle interval, and is updated every half cycle.

Figure 1: Voltage Sag Example: Three-Phase Voltage Waveform Samples

To calculate the rms voltage, the sampled voltages are squared and averaged over a window with a one-cycle duration, as described in the following equation:

where N is the number of samples per cycle, Vi is the sampled voltage waveform, and k=1,2,3, etc.

IEEE 1564 recommends that the sampling rate be synchronized to the power frequency. That is, the sampling frequency is not a fixed number of samples per second but a fixed number of samples per cycle. This synchronization to the power frequency (also referred to as “phase-locked-loop” or PLL) is essential for the quantification of harmonic distortion and phase angle change calculations. For multi-channel measurements, the rms voltage versus time is calculated for each channel separately.

A voltage sag or voltage swell can be characterized by its duration and its retained voltage. The duration is the time that the rms voltage stays below the threshold. The retained voltage is the lowest rms voltage during the event. Instead of retained voltage, the depth may be used, which is the difference between the retained voltage and a reference or declared voltage.

To determine the sag duration, a threshold setting is needed. This threshold can be defined in multiple ways, such as a percentage of the nominal voltage; a percentage of the long-term average voltage at the location; or a percentage of the rms voltage just prior to the event start. For measurements in low-voltage and medium-voltage networks, the declared or nominal voltage should be used. This value is the most relevant one for the performance of end-use equipment. In low-voltage networks the nominal voltage should be used in all cases. In medium voltage, a different declared voltage may be used to incorporate the primary/secondary ratio of the step-down transformers.

Different threshold values may be used for obtaining the starting and ending instants of the sag. The ending threshold could be higher than the starting threshold by an amount that is referred to as the “hysteresis voltage”. In that case the voltage sag begins when Vrms(1/2) falls below the sag threshold, and ends when Vrms(1/2) is equal to or above the sag threshold plus the hysteresis voltage.

IEEE 1564 recommends the starting threshold be set to 90% of the declared voltage or of the sliding reference voltage. In the event that a different ending threshold is used, the recommended value for the ending threshold is 91% of the declared voltage or of the sliding reference voltage.

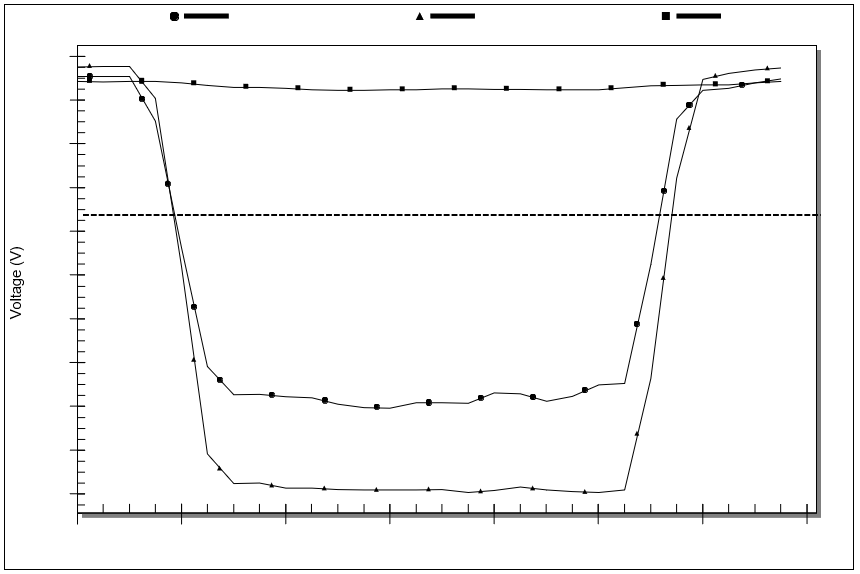

Figure 2: Voltage Sag Example: Three-Phase Voltage RMS Samples with Sag Threshold

Voltage swells can be characterized in the same way as voltage sags. The rms voltage is again used as a characteristic versus time. The single-event indices are the “duration” and the “retained voltage” or “maximum swell voltage magnitude” [2]. The duration equals the amount of time the rms voltage is above the swell threshold. The retained voltage is the highest value of the rms voltage. The recommended value for the swell threshold is 110% of the declared voltage or of the sliding-reference voltage.

Figure 2 presents the rms voltage samples for the voltage sag of Figure 1. The dashed line indicates the voltage sag threshold, which is chosen as 90% of the phase-neutral base voltage of 7.2 kV. If we consider the three phases individually, two phases show a voltage sag of 9.5 cycles duration below the threshold. The retained voltage is 5.21 kV for Phase B.

IEEE 1564 presents voltage sag energy as the energy in the voltage sag event, or the “missing energy” in the voltage waveform. The voltage sag energy is the duration of an interruption that would result in the same loss of energy for a resistive load. The voltage sag energy can also be defined as the non-delivered energy to a resistive load, divided by the rated power of that load. Specifically, IEEE 1564 defines the voltage sag energy characteristic EVS in the following equation:

where V(t) is the rms voltage during the event and Vnom is the nominal voltage.

For voltage sags involving more than one phase, the voltage sag energy is defined as the sum of the voltage sag energy in the individual channels. In case a three- phase approach is used, the voltage sag energy may be calculated from the characteristic voltage as a function of time, with V(t) the characteristic voltage as a function of time.

IEEE 1564 recommends that the voltage sag energy index not be used with short-duration interruptions. A “voltage swell energy” can be defined in the same way as the voltage sag energy.

The voltage sag severity is calculated from the retained voltage in per unit and the duration of a voltage sag in combination with a reference curve. Events with longer event duration and lower magnitudes will have larger values of voltage sag severity index. It is recommended to use the ITIC Curve or SEMI F47 curve as a reference, but the method works equally well with other reference curves.

For multi-channel measurements, the voltage sag magnitude (retained voltage) is the lowest magnitude for the individual phases. The start time of the sag is the time when the rms voltage in one of the phases drops below the sag-starting threshold. The ending time of the sag is the time when all rms voltages have recovered above the sag-ending threshold. The duration is obtained as the time difference between the start time and the stop time. Note that the event may end in a different phase as the one in which it started.

From the three sampled waveforms in the three phases, a characteristic voltage as a function of time may be obtained. Characteristic voltage is the minimum of the one-cycle, sliding-window rms value of the line-neutral voltage with the zero-sequence voltage removed (VA-V0, VB-V0, and VC-V0) and the line-line voltage (VAB, VBC, and VCA) divided by the square root of three. The lower characteristic voltage is the smallest of the six sliding- window rms voltages. The upper characteristic voltage or PN factor, is the largest of the six sliding-window rms voltages. See Bollen [3] and Sannino et al. [10]

Analyzing the event shown in Figure 2 as a three-phase event results in the characteristic voltage as shown in Figure 3. The lower characteristic voltage has been calculated as the lowest value of the six rms voltages. Like before, the calculation has been updated every half cycle. The resulting duration of the three-phase events is again 9.5 cycles, but the remaining (characteristic) voltage is 4.68 kV or 65% of the nominal phase-neutral voltage of 7.2 kV.

Figure 3: Characteristic Voltage as a Function of Time

As input to the site indices, the single-event characteristics are used as obtained from all events recorded at a given site over a given period, typically one month or one year. For the two-index method, a number of alternatives are presented. Each can be summarized as a count of events within a certain range of retained voltage and duration. For single-index methods, the site index is the sum of the single-event indices of all events recorded within the given period.

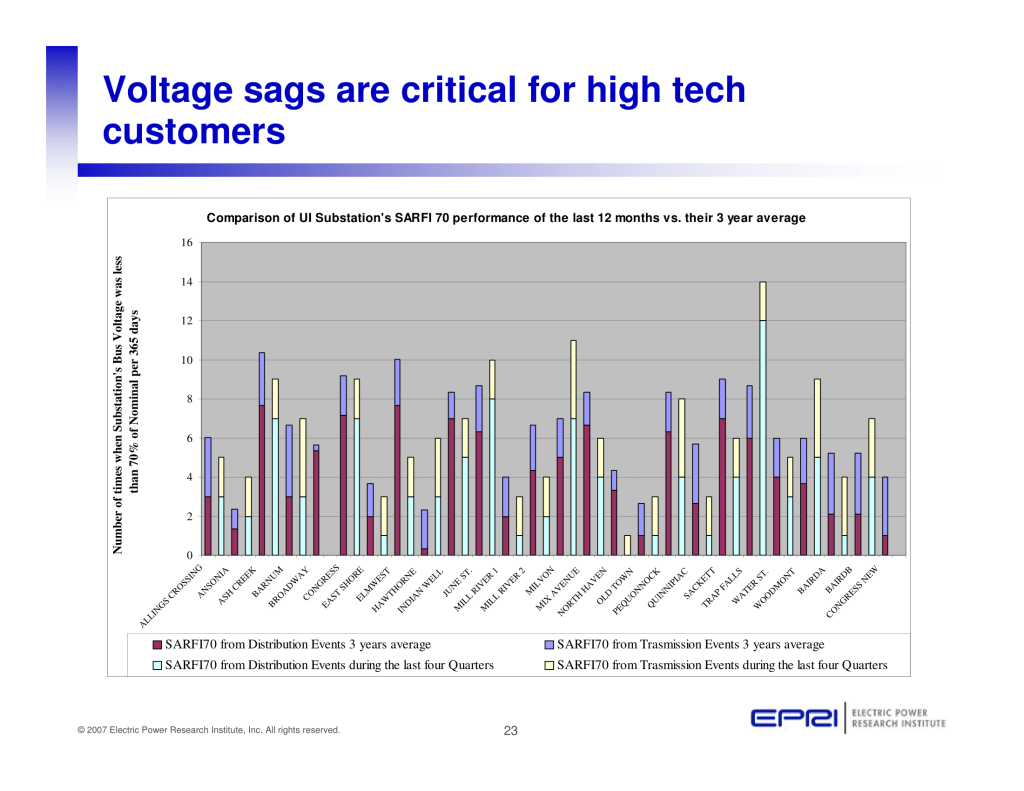

SARFI is an acronym for the System Average RMS Variation Frequency Index. It is a power quality index that provides a count or rate of voltage sags, swells, and/or interruptions for a system. The SARFI index was first described by Brooks in [8]. The size of the system is scalable: it can be defined for a single monitor, a single customer service, a feeder, one or more substations, or an entire power delivery system. There are two types of SARFI indices: SARFI-X and SARFI-Curve.

SARFI-X corresponds to a count or rate of voltage sags, interruptions and/or swells below/above a specified voltage threshold. For example, SARFI-70 considers voltage sags and interruptions that are below 70% of the reference voltage. SARFI-110 considers voltage swells that are above 110% of the reference voltage. Both types of SARFI indices are meant to assess short-duration rms variation events only, meaning that only those events are included in its computation with durations less than the minimum duration of a sustained interruption as defined by IEEE Std 1159, which is one minute [7].

SARFI-Curve corresponds to a rate of voltage sags below an equipment compatibility curve. For example, SARFI- ITIC considers voltage sags and interruptions that are below the lower ITIC curve.

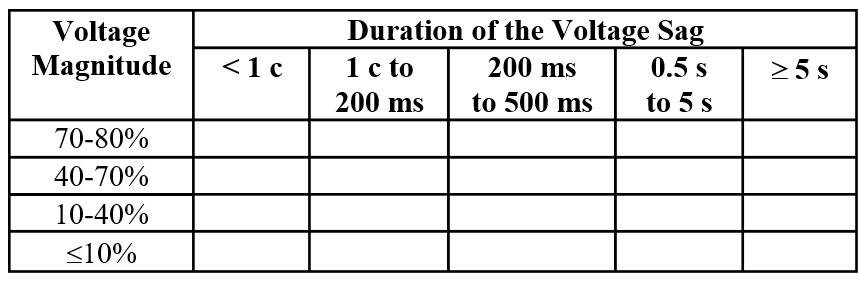

A commonly used method of presenting the performance of a site is by means of a voltage sag table. The columns of the tables represent ranges of voltage sag duration, while the rows represent ranges of retained voltage. Each cell in the table gives the number of events with the corresponding range of retained voltage and duration. Each event (that is, each combination of retained voltage and duration) is tabulated in only one cell of the table. Different values are in use for the boundaries between the cells.

Table 1: Voltage Sag Table from IEC 61000-4-11

IEEE 1564 presents guidelines on using the voltage sag tables presented by the International Union of Producers and Distributors of Electrical Energy in Europe (UNIPEDE), IEC 61000-2-8, and IEC 61000-4-11 (See Table 1).

The sag energy method of characterization uses three site indices: number of events per site; “total lost energy” per site and “average lost energy” per event.

IEEE 1564 presents a Sag Energy Index (SEI), which is the sum of the voltage sag energies for all qualified events at a given site during a given time period. The indices are usually calculated monthly and/or annually. The Average Sag Energy Index, or ASEI, is the average of the voltage sag energies for all qualified events measured at a given site during a given period. When using voltage sag energy indices, IEEE 1564 recommends to not include short-duration interruptions, as one short-duration interruption may have a larger contribution to the index than all voltage sags together.

The calculation of site indices for the voltage sag severity method is very similar to the calculation of site indices based on the voltage sag energy. The Total Voltage Sag Severity is the sum of the voltage sag severity for all qualified events at a given site during a given period. The Average Voltage Sag Severity is the average of the voltage swell severity for all qualified events measured at a given site during a given period.

Aggregation in IEEE 1564 refers to the data reduction technique of collecting many distinct measurement components into a single aggregate event for the purpose of computing site and system indices. How the measurements are combined depends on the specific needs of a particular analysis session.

Measurement Aggregation: Many monitoring instruments will record one or more phases during an event. For example, a three-phase voltage sag may result in a meter recording one measurement for each phase. In conducting measurement aggregation, IEEE 1564 recommends representing the multiple phase measurements as only one measurement. A common practice is to choose the voltage channel that exhibits the greatest deviation from nominal voltage. Alternatively, the characteristic voltage, as defined in Section II.F, can be used.

Time Aggregation: The time aggregation is counting a single event if there is a succession of events within a short time, generally caused by a single power system event. An example would be multiple sag events during an automatic reclosing operation. This is the generally accepted practice in indexing voltage sag events. If the customer equipment is impacted by a voltage sag event, it is unlikely that the equipment will be up and running and impacted by a succeeding event during the aggregation time period. Another example is that the survey results that were published in IEEE journals from the EPRI Distribution System Power Quality (DPQ) Monitoring Project used 60-second aggregation time, but the project also explored using 120 seconds and 300 seconds. See Sabin [4] or Sabin et al. [5].

Spatial Aggregation: This refers to finding the worst voltage sags from more than one monitoring point. Spatial aggregation has also been employed when multiple meters are employed to monitor only a single phase of a system. In this case, three meters each monitoring one phase of a feeder can be combined to give the voltage sag performance of the bus supplying the feeder.

When using spatial aggregation to reduce the number of rms variation measurements, the measurements from multiple monitoring instruments are combined into a single measurement. An application is in computing rms variation indices at a single substation that is monitored at multiple buses. Another example is computing rms variation indices for a single industrial facility that is monitored at each service entrance of its supplying feeders. See Dettloff et al. [9].

It is not unusual during the course of a monitoring project to experience periods when an instrument is off-line due to instrument calibration or malfunction. Poor data management practices can also result in missing measurements. When combining indices taken from different monitoring sites, it is vital that the total time that each monitor was available is taken into account.

IEEE 1564 includes guidelines on how to compute indices for more than one power quality monitoring site (that is, system indices) from weighted averages or from weighted percentiles. The system indices are defined such that they may be applied to systems of varying size. System indices may be calculated for the whole system operated by a network company; for all networks at one voltage level over a whole country or geographical area; for a group of feeders; etc. Other issues related to system indices presented in IEEE 1564 include site selection, sampling weighing factors, and statistical values.

The SARFI indices for a system are obtained as the average of the indices for the different sites. The SARFI value may be interpreted as quantifying the “average voltage quality” over the whole system or the part of the system being considered. When using SARFI indices to describe individual sites, it is possible to give a 95th percentile to characterize the quality of the whole system.

When voltage sag tables are used, both average values over all sites and 95th percentile values can be used. When average values are used, weighting of the values may be considered. Weighting is also possible when using the 95th percentile, but it is less useful unless a very large number of sites is being monitored. Each element of the voltage sag table should be considered as one index to which the statistical processing (average, 95th percentile, etc.) has to be applied. The resulting table for the whole system does not correspond to any individual site.

When using voltage sag energy indices, system indices are calculated by taking the average value of the site indices. See Thallam et al. [6]. The average sag energy index ASEI for the whole system is obtained by dividing the sum of the site values with the number of sites involved. The system index for voltage-sag severity should be obtained from the site indices in the same way as for the other indices: either as a weighted average or as a 95th percentile.

The next activities of the IEEE P1564 Task Force include promoting the new standard at international conferences. The task force will sponsor a panel session on voltage sag indices at the 2015 IEEE Power & Energy Society General Meeting in Denver, Colorado, USA. Discussion of IEEE 5164 at meetings during two IEEE conferences per year will result in a short- and long-term revision plan. More information will be posted on the task force website: http://grouper.ieee.org/groups/sag/.

[1] IEEE, 2014 IEEE Std 1564-2014 Guide for Voltage Sag Indices.

[2] IEC, 2008, IEC 61000-4-30 ed. 2.0, Electromagnetic Compatibility – Power Quality Measurement Methods.

[3] M.H.J. Bollen, 2003, “Algorithms for Characterizing Measured Three-Phase Unbalanced Voltage Dips,” IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, vol. 18, no. 3, 937-944.

[4] D.D. Sabin, 1996, An Assessment of Distribution System Power Quality, Volume 2: Statistical Summary Report. EPRI, Palo Alto.

[5] D.D. Sabin, T.E. Grebe, A. Sundaram, 1999, “RMS voltage variation statistical analysis for a survey of distribution system power quality performance,” Proceedings of IEEE Power Engineering Society Winter Meeting, vol.2, 1235-1240.

[6] R.S. Thallam, G.T Heydt, 2000, “Power acceptability and voltage sag indices in the three phase sense,” IEEE Power Engineering Society Summer Meeting, vol.2, 905-910.

[7] IEEE, 2009, IEEE Std 1159-2009 Recommended Practice for Monitoring Electric Power Quality.

[8] D.L Brooks, R.C Dugan, M. Waclawiak, A. Sundaram, 2008, “Indices for assessing utility distribution system RMS variation performance,” IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, vol.13, 254- 259.

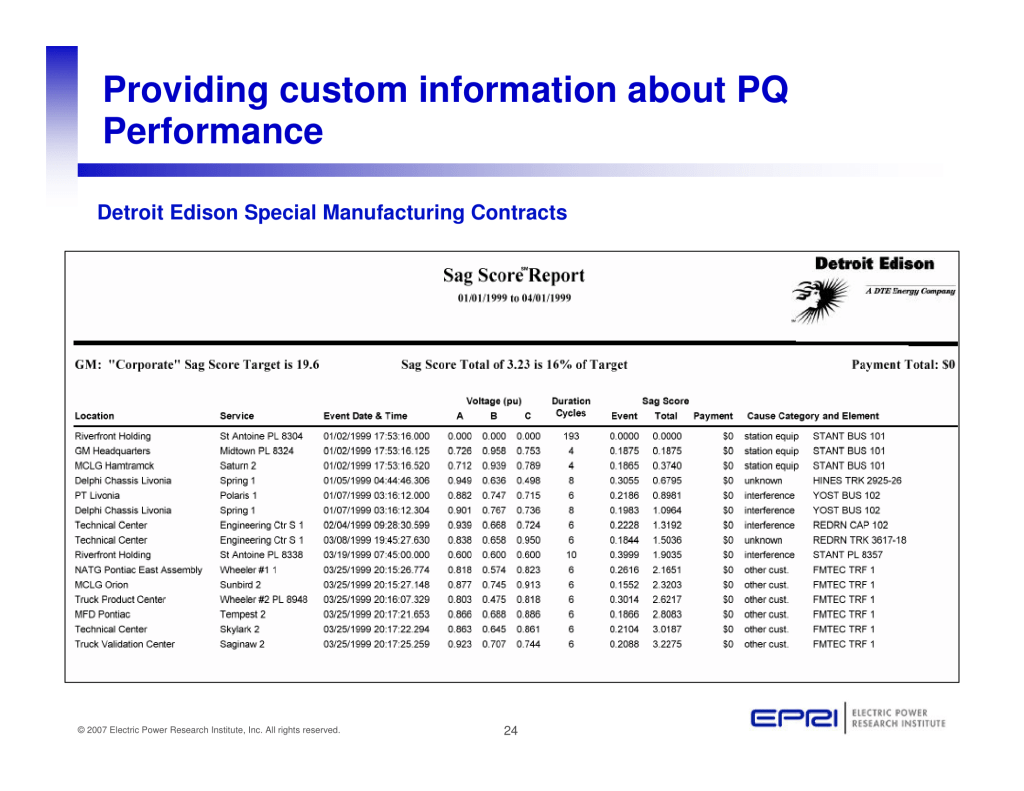

[9] A. Dettloff, D.D. Sabin, 2000, “Power quality performance component of the special manufacturing contracts between power provider and customer,” Proceedings of Ninth International Conference on Harmonics and Quality of Power (ICHQP), 2000., vol.2, no., 416-424.

[10] A. Sannino, M.H.J. Bollen, J. Svensson, 2005, “Voltage tolerance testing of three-phase voltage source converters,” IEEE Transactions on Power Delivery, vol.20, no.2, 1633- 1639.

Published by Dr. Kerstin Kunde, Dr.-Ing. Holger Däumling, Dipl.-Ing. Ralf Huth, Dipl.- Ing. Hans-Werner Schlierf and Dr.-Ing. Joachim Schmid

As the number of non-sinusoidal sources and loads in the network continues to grow, the importance of information concerning the quality of the current and the voltage becomes ever more important. Each deviation in frequency can be regarded as harmonic contamination of the network that can cause issues for the network operator and the users. It is questionable, however, whether the instrument transformers so far used for measuring the Power Quality can cope with the accuracy requirements for the analysis of network quality.

Instrument transformers of various different construction and from various different manufacturers vary greatly in their frequency response behaviour. The causes of this are varied and extend from manufacturing tolerances in a series up to various different operating conditions. For the frequency response behaviour, in addition to the structure, the most significant responsible factors are the voltage level and the connected load impedance. Measurements have shown that the resonance points move to lower frequencies the higher the voltage level. With the connected load impedances (protection, measuring system), the frequency behaviour is generally unknown. However, it has a considerable influence on frequency response.

Inductive voltage transformers convert the high voltage to a low voltage signal using the transformer principle. In this case the secondary voltage behaves in the linear area of the “opened” transformer in a reciprocal manner to the response ratio.

Because of the harmonic contamination in the network, users require that the network operators demonstrate and ensure the quality of the prepared energy supply is in accordance with DIN EN 61000-4-30 (VDE 0847-4-30) [1] and DIN EN 50160 [2]. From the point of view of the network operator it is important to determine the cause of the harmonic contamination of the network, in order to be able to carry out counteracting measures. The execution of the required measurement of current and voltage should, where possible, be carried out using the existing measuring systems from the inductive or capacitive instrument transformers.

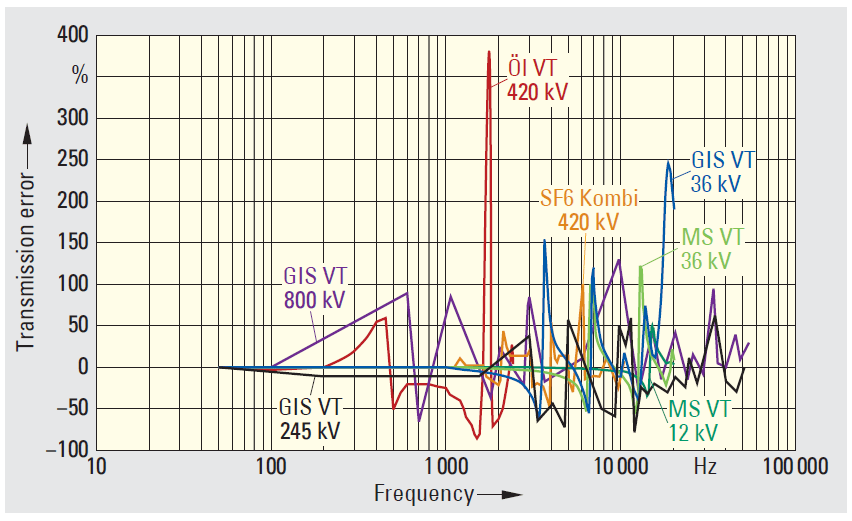

Fig 1. Transmission errors with various different inductive instrument transformer types

Because of design restrictions, instrument transformers are used for transmission as close as possible to the illustration of the primary technology measuring parameters, such as current or voltage. This requirement of the response behaviour applies to the range of measurement frequency and is ensured by the instrument transformer manufacturers. In order to be able to assess the network quality and compliance with existing standards as well as at the fundamental frequency we need to accurately measure harmonics up to 50 times the rated frequency in terms of both magnitude and phase angle.

Depending on the selected insulation (oil-paper, gas or cast resin) various different geometric structures of the primary and secondary windings are produced, and these lead to various different response behaviours depending on the concentrated parameters capacitance, inductance and resistance.

On the other hand, capacitive voltage transformers produce the secondary voltage as a transmission ratio between the primary and secondary capacitance. They consist of a stack of condensers wired in series and an inductive unit required for the power provision on the low voltage side. Capacitive voltage transformers are primarily structured with a mixed dielectric in the condenser stack (C1/C2) in order to achieve the class accuracy even in various different temperature ranges.

Conversion with inductive current transformers is carried out using the transformer principle, as is the case with the voltage transformers. However, the windings are almost short-circuited.

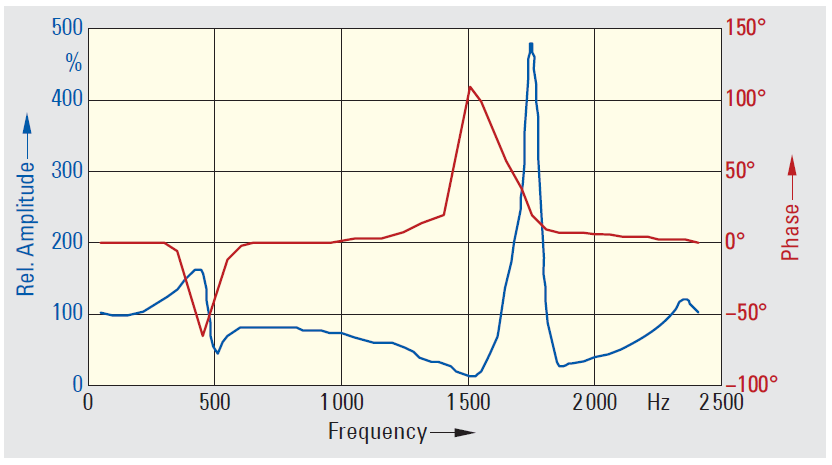

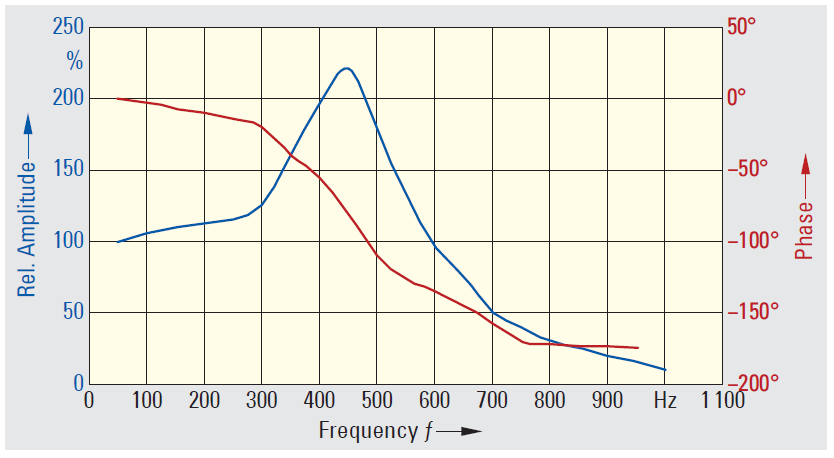

Fig 2. Amplitude and phase errors of an inductive voltage transformer at various different frequencies

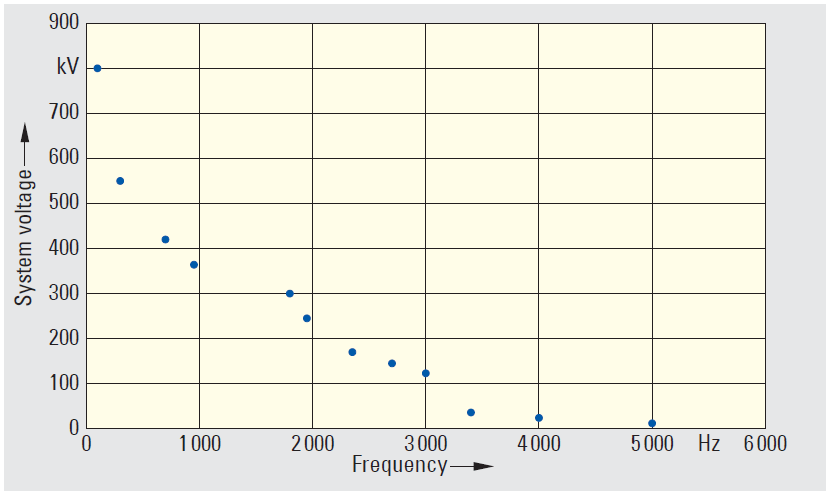

Fig 3. Frequency of the first resonant point for various different voltage levels

Fig 4. Amplitude and phase errors of a capacitive voltage transformer

The frequency response of inductive and capacitive voltage transformers is determined by the geometrical structure of each individual product. For this reason, there may be differences in the resonant frequencies between oil, gas and cast resin insulated voltage transformers. The influencing factors are:

On inductive current transformers the transmission property is less severely determined by the capacitive layer influences, so that a higher linear transmission frequency spectrum is to be expected. This process is supported by light loading. The size of the errors that can arise in the various different converter types in the frequency range up to 50 kHz is shown in Fig. 1. For example, Fig. 2 shows the error in an oilpaper insulated, inductive 420 kV voltage converter for the frequency range up to 2.5 kHz according to magnitude and phase.

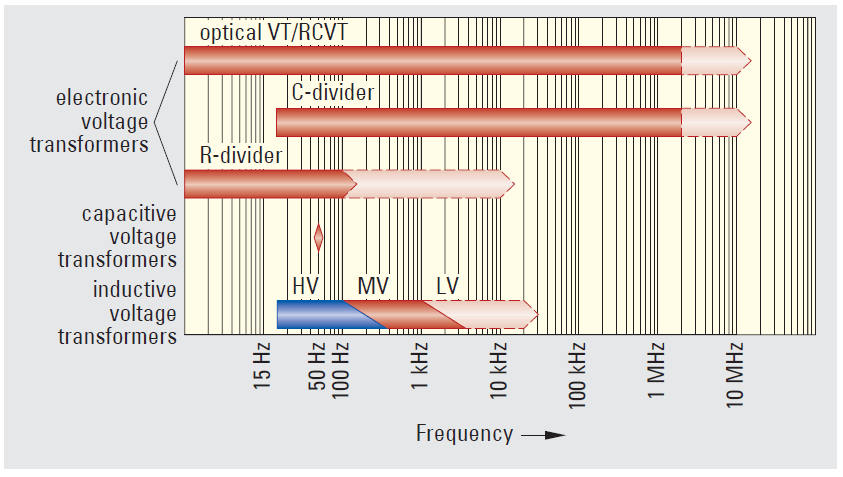

For the same types of design and insulation principles we can determine that the occurrence of the first resonance point falls depending on the voltage level. That is shown in Fig. 3 using various different voltage transformers. Capacitive voltage transformers are set to the nominal frequency of 50 Hz or 60 Hz. The accuracy is guaranteed only for a narrow band (Fig. 4). The lowest resonant frequency is a few hundred Hz. The frequency range to which the various different technologies are suited is clearly shown in Fig. 5. The class error is taken into account here.

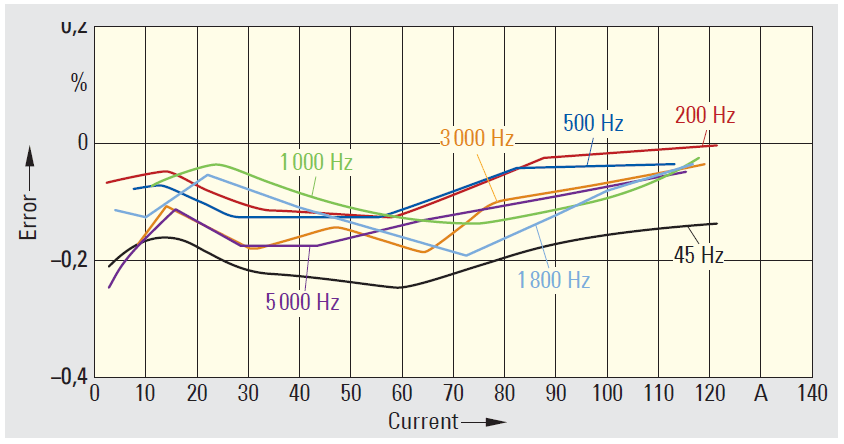

Inductive current transformers transmit the signals over several kHz without major errors. Fig. 6 shows the measurements at various different frequencies. The error can be ignored up to 5 kHz. However, the existing measuring equipment does not allow differentiation between amplitude and phase errors.

Also, investigations were undertaken to show the difference between primary and secondary signals with frequencies overlaid in different ways. An amplitude or phase measurement is not undertaken in this investigation. The result of this analysis also confirms the suitability of inductive current transformers for the measurement of higher frequency harmonics.

Fig. 5 Frequency response behaviour of various different voltage transformer technologies

in accordance with IEC/TR 61869-103 [3]

Fig. 6 Amplitude errors in an inductive current transformer at various different frequencies

Because the majority of protection principles are based on fundamental frequency values, protection systems evaluate these signals in the permissible frequency working range. Digital protection devices are capable, in this case, of precisely filtering out unwanted frequency components.

Although harmonics play a subordinate role in the protection, there are also protection principles that use them. The current differential protection assesses the 2nd to 5th harmonics for stabilization purposes in the current. This is not critical because current transformers transmit these frequencies without any problems. Earth short wiper principles are based on the evaluation of higher frequency current and voltage signals (< 5 kHz) in the first periods after the occurrence of the error. The principle is used exclusively in the distribution network, in other words, at medium voltage. At this voltage level, the frequency response behaviour of the voltage transformers is considerably better. Principles for protection of capacitor banks are also based on the assessment of higher frequency signals. The protection criteria that are used use current measuring principles.

Both inductive and capacitive voltage transformers, at the current state of technology, are not suited for the measurement of harmonics without additional measures, because of the

occurrence of resonant frequencies, particularly at high voltage. Both types of transformers are dimensioned for the measurement and protection at nominal frequencies. Resonances between the winding inductance and the stray capacitance (between the layers) can cause large amplitude and phase errors.

If the measuring task is the measurement of higher frequency harmonics, then we need to use RC dividers for high voltage and C- or R-dividers for medium voltage. These are suitable both for the measurement of harmonics and for the measurement of DC voltages (albeit with negligible power output). Inductive current transformers transmit harmonics up to several kHz in correct phase and with negligible errors. If you need more detailed information concerning the resonant frequencies of a conventional measuring converter this should initially be requested from the instrument transformer manufacturers.

[1] DIN EN 61000-4-30 (VDE 0847-4-30): 2009-09 Electromagnetic Compatibility (EMC) – Part 4-30: Test and measuring procedure – procedure for measuring the voltage quality. VDE VERLAG

[2] DIN EN 50160:2011-02 Voltage characteristics in public electricity supply networks. Berlin: Beuth

[3] IEC/TR 61869-103:2012-05 Instrument transformers – The use of instrument transformers for power quality measurement. Geneva / Switzerland: Bureau Central de la Comission Electrotechnique Internationale

Dr. Kerstin Kunde is responsible for product life-cycle management in the Business Segment Instrument Transformers at Siemens AG in Erlangen.

Email: kerstin.kunde@siemens.com

Dr.-Ing. Holger Däumling is Managing Director of Ritz Instrument Transformers GmbH in Hamburg.

Email: info@ritz-international.com

Dipl.-Ing. Ralf Huth is Asset Manager for Substations at Tennet TSO GmbH in Bayreuth.

Email: ralf-huth@tennet.eu

Dipl.- Ing. Hans-Werner Schlierf was, until recently, Manager of the Service Teams Primary Technology at Amprion GmbH in Lampertheim.

Email: info@amprion.net

Dr.-Ing. Joachim Schmid has global responsibility for R&D in the Instrument Transformer Sector at Siemens Schweiz AG in Zürich.

Email: joachim.schmid@siemens.com

Published by Peter W. Sauer, Department of Electrical and Computer Engineering

University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, September 16th, 2003

Published in Power Systems Engineering Research Center (PSERC) Background Paper on Grid Reliability.

Link: https://pserc.wisc.edu/resources/background.aspx

Reactive power is a quantity that is normally only defined for alternating current (AC) electrical systems. Our U.S. interconnected grid is almost entirely an AC system where the voltages and currents alternate up and down 60 times per second (not necessarily at the same time). In that sense, these are pulsating quantities. Because of this, the power being transmitted down a single line also “pulsates” – although it goes up and down 120 times per second rather than 60. This power goes up and down around some “average” value – this average value is called the “real” power and over time you pay for this in kilowatt-hours of energy. If this average value is zero, then all of the power being transmitted is called “reactive” power. You would not normally be charged for using reactive power because you are consuming some energy half the time, and giving it all back the other half of the time – for a net use of zero. To distinguish reactive power from real power, we use the reactive power unit called “VAR” – which stands for Volt-Ampere-Reactive. Voltage in an electrical system is analogous to pressure in a water system. Current in an electrical system is analogous to the flow of water in a water system.

Let’s go back to this notion that voltage and current may not go up and down at the same time. When the voltage and current do go up and down at the same time, only real power is transmitted. When the voltage and current go up and down at different times, reactive power is being transmitted. How much reactive power and which direction it is flowing on a transmission line depends on how different these two times are.

Two extreme examples of the time relationship between voltage and current are found in inductors and capacitors. An inductor is a coil of wire that is used to make motors. A capacitor is made of parallel conductive plates separated by an insulating material. The electrical properties of these two devices are such that if they are both connected to the same AC voltage source, the inductor absorbs energy during the same “half cycle” that the capacitor is giving energy. And similarly, the inductor produces energy during the same “half cycle” that the capacitor absorbs energy. Neither of them absorbs any real power over one complete cycle. Thus, when a motor needs reactive power, it is not necessary to go all the way back to electric power generators on the transmission grid to get it. You can simply put a capacitor at the location of the motor and it will provide the VARs needed by the motor. This relieves the generator and all the lines between the generator and the motor of having to transmit those VARs. They are provided “locally” by the capacitor. This means that with the capacitors installed, the current in the lines will be smaller than when the capacitors are not installed. This is a good thing because current in the lines causes heat and every line can only handle a limited amount of current. Since the line current is smaller when the capacitors are installed, the voltage drop along all the lines is also less, making it more likely that the motor will have a voltage closer to the desired value. When there are not enough VARs flowing locally to the loads, the generators must supply them remotely, causing unnecessarily large currents and a resulting drop in voltage everywhere along the path.

While there are numerous physical analogies for this quantity called reactive power, one that is reasonably accurate is the process of filling a water tower tank with water – one bucket at a time. Suppose you want to fill a water tower tank with water, and the only way that you can do that is by climbing up a ladder carrying a bucket of water and then dumping the water into the tank. You then have to go back down the ladder to get more water. Strictly speaking, if you simply go up a ladder (not carrying anything) and come back down (not carrying anything), you have not done any work in the process. But, since it did take work to go up the ladder, you must have gotten all that energy back when you came down. While you may not feel that coming down the ladder completely restores you to the condition you were in before you went up, ideally, from an energy conversion viewpoint, you should! If you don’t agree, get out your physics book and check out the official definition of doing work.

OK, if you still don’t agree that walking up a ladder and coming back down does not require any net work, then think of it this way. Would you pay anyone to walk up a ladder and back down without doing anything at the top? Probably not. But, if they dumped a bucket of water in the tank while they were at the top, then that would be something worth paying for.

When you carry a bucket of water up the ladder you do a certain amount of work. If you dump the water at the top and carry an empty bucket down, then you have not gotten all your energy back (because your total weight coming down is less than going up), and you have done work during that process. The energy that it takes to go up and down a ladder carrying nothing either way requires reactive power, but no real power. The energy that it takes to go up a ladder carrying something and come down without carrying anything requires both real power and reactive power.

A reminder here is that power is the time rate of energy consumption, so consuming 500 Watts of real power for 30 minutes uses 250 Watt-hours of energy (or 0.25 kilowatt- hours which costs about 2.5 cents to generate in the U.S.). The analogy is that voltage in an AC electrical system is like the person going up and down the ladder. The movement of the water up the ladder and then down into the tank is like the current in an AC electrical system.

Now, this pulsating power is not good in an electrical system because it causes pulsations on the shafts of motors and generators which can fatigue them. So, the answer to this pulsation problem is to have three ladders going up to the water tower and have three people climb up in sequence (the first person on the first ladder, then the second person on the second ladder, then the third person on the third ladder) such that there is always a steady stream of water going into the tank. While the power required from each person is pulsating, the total result of all three working together in perfect balanced, symmetrical sequence results in a constant flow of water into the tank – this is why we use “3-phase” electrical systems where voltages go up and down in “sequence” – (first A phase, then B phase, and finally C phase).

In AC electrical systems, this sequential up/down pulsation of power in each line is the heart of the transmission of electrical energy. As in the water tower analogy, having plenty of water at ground level will not help you if you cannot get it up into the tower. While you may certainly be strong enough to carry the bucket, you cannot get it there without the ladder. In contrast, there may be a ladder, but you may not be strong enough to carry the water. However, the people do take up room around the water tower and limit how much water can go up and down over a period of time – just as reactive power flow in an electrical system requires a larger current which limits how much real power can be transmitted.1

To make the system more reliable, we might put two sets of three ladders leading up to the tank on the tower. Then, if one set fails (maybe the water plus the person get too heavy and the ladder breaks), the other set picks up the slack (that is, has to carry more water). But, this could eventually overload the second set so that it too fails. This is a cascading outage due to the overloading of ladders.

1 Another analogy that says that reactive power is the “foam on the beer” is fairly good here because the space in the glass is taken up by the useless foam – leaving less room for the “real” beer.

In terms of this water-carrying analogy, the frequency of going up and down the ladder should be nearly constant (that, is like our 60 cycles per second electrical frequency). So, when more water is needed, the amount that each person carries up the ladder must get bigger (since they are not allowed to go faster or slower). Well, if this water gets too heavy, either the ladder might break, or the person might get too tired to carry it. We could argue that if the ladder breaks, that is like the outage of a transmission line that either sags or breaks under the stress of too much current. There are devices called relays in an electrical system that are supposed to sense when the load is too much and send a signal to a “circuit breaker” to remove the line from service (like removing the set of three ladders). If the person gets too tired, we could again stretch this analogy to say that this is like not having enough reactive power (resulting in low voltage). In the extreme case, the person might “collapse” under the weight of the water that the person is being asked to carry. If it happens to one person, it will probably happen to many of them. In the electrical system this could be considered a “voltage collapse”. While there are “undervoltage relays,” there are no relays in the system to directly sense the problem that the voltage is about to collapse.

Remember, the people going up and down the ladders do not absorb or produce energy over a complete cycle and are therefore analogous to reactive power. It is the water going up the ladder to fill the tank that absorbs real power that must be paid for. But, the real power cannot be delivered without the reactive power. And, if there is not enough reactive power (like with people going up and down the ladders), the real power delivery will eventually fail.

In summary, a voltage collapse occurs when the system is trying to serve more load than the voltage can support. A simulation has been prepared to illustrate voltage collapse by simply using a system with an Eastern generator and customer load, a Western generator and customer load, and East to West transmission lines. In the simulation, the Eastern generator has a constrained supply of reactive power and progressive line outages for unspecified reasons lead to a voltage collapse even when reactive power supply is ample at the Western generator.

In contrast to all of this, you could route a hose up the side of the water tower and simply turn on the water and let the water flow in the hose to fill up the tank. The water pressure is like voltage, and the water flow is like current. This type of system would be a direct current (DC) system and would not involve reactive power at all. However, the concept of voltage collapse is not unique to AC systems. A simple DC system consisting of a battery serving light bulbs can be used to illustrate how too much load on a system can lead to a condition where voltages drop to a critical point where “adding more load” results in less power transmission – a form of voltage collapse.

| Publisher Contact Information |

|---|

| Peter W. Sauer PSERC Site Director Grainger Chair Professor Department of Electrical & Computer Engineering University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign 1406 W. Green St. Urbana, IL 61801 Phone: 217-333-0394 E-mail: sauer@ece.uiuc.edu |

| Power Systems Engineering Research Center 428 Phillips Hall Cornell University Ithaca, NY 14853-5401 Phone: 607-255-5601 |

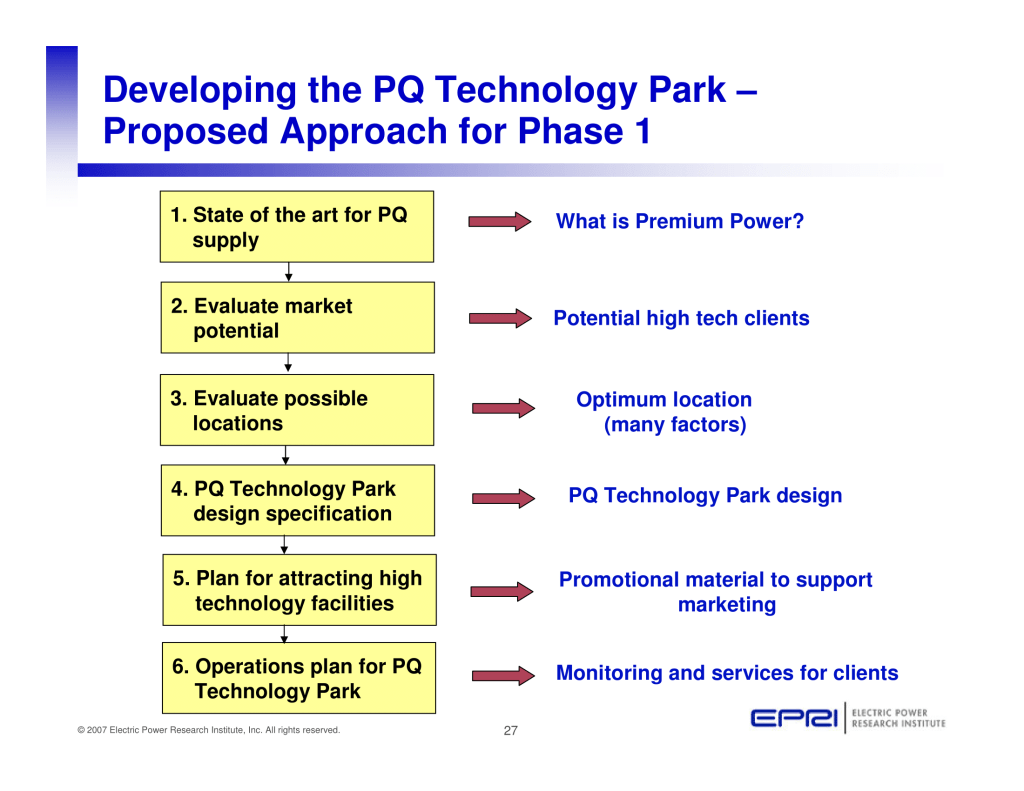

Published by Mark McGranaghan, Director, Distribution, Power Quality, and Intelligrid Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI), Warsaw June 25th, 2008

Published by Terence (Terry) E. Chandler, Founder and Director of Power Quality Inc.

Email: terryc@powerquality.org

Presented in Powermetrix Webinar on Tuesday, March 2nd 2021.

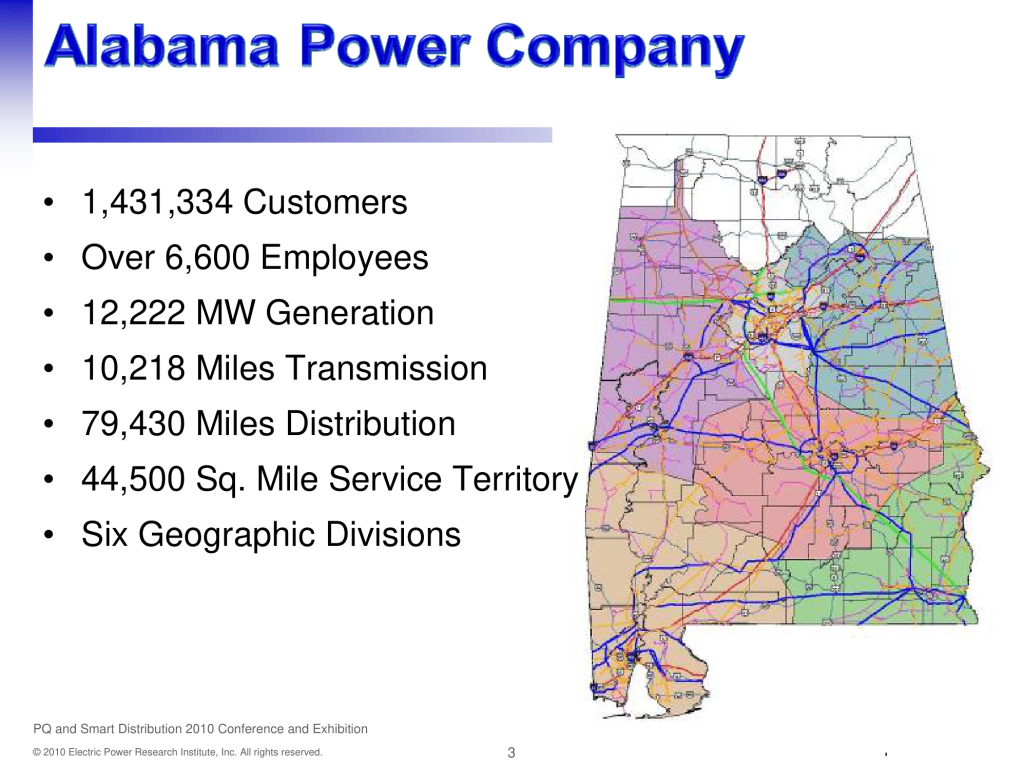

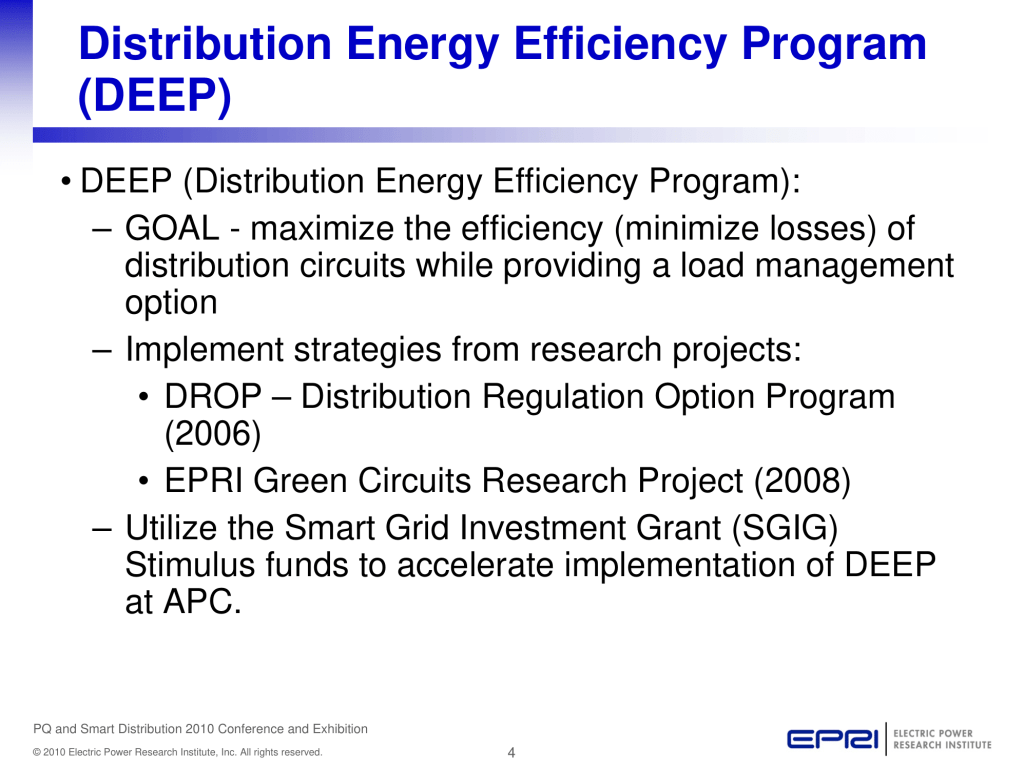

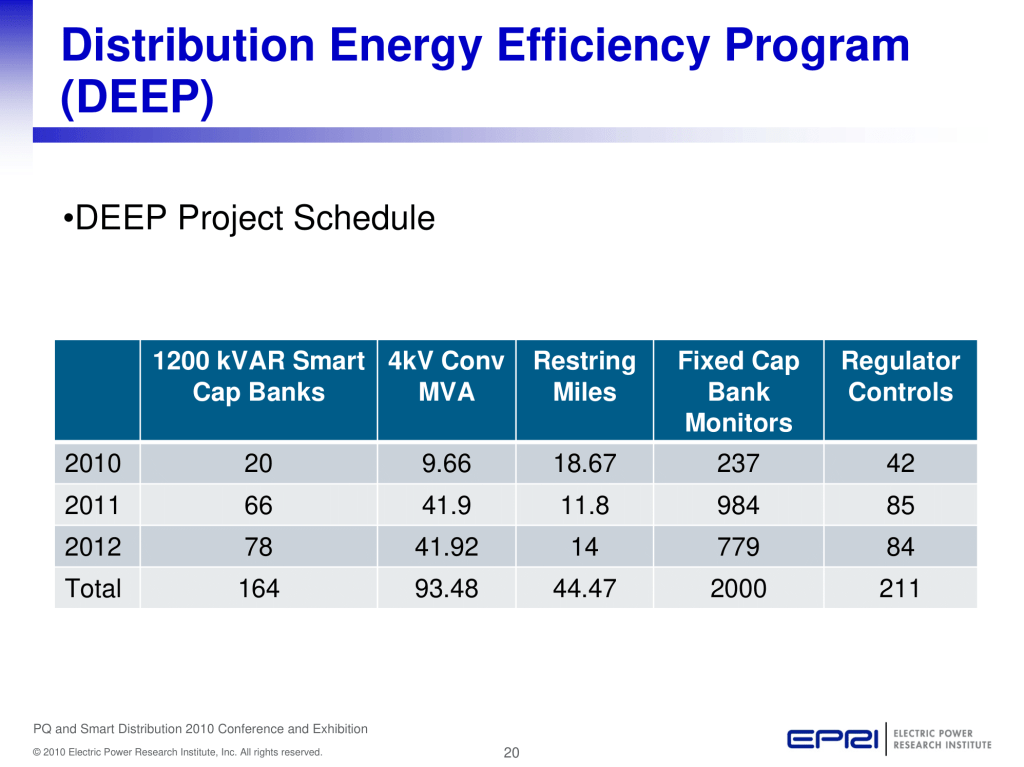

Published by Chuck Wallis, Distribution Engineering Services Manager, Alabama Power/Southern Company

Presented at EPRI PQ and Smart Distribution 2010 Conference and Exhibition:

Transporting You into the 21st Century Distribution System, June 14th – 17th, 2010

Published by Charlie Williams, Senior Systems Consultant, S&C Electric Company

Published by Mark Stephens, P.E. and Alden Wright, P.E., CEM EPRI, Knoxville

Presented at EPRI PQ and Smart Distribution 2010 Conference and Exhibition:

Transporting You into the 21st Century Distribution System, June 14th – 17th, 2010

Published by David Mueller, P.E., Manager, Power System Studies, Electrotek Concepts, Inc., Knoxville, Tennessee, USA

Email: davem@electrotek.com

Presented at 2010 Georgia Tech Fault Disturbance Analysis Conference

Abstract

Wind power plants are the fastest growing power generation source, and this trend is expected to continue. This paper describes the different types of wind power turbine electrical characteristics, using the classification system as proposed by the WECC. It then discusses the relevant power quality issues of the wind turbine types and collector systems. A case study is used to illustrate the issue of harmonics and compliance with the IEEE-519 recommended limits for harmonics.

Keywords: Wind Power Plants, Utility Scale Wind Power, Flicker, Harmonics, Low Voltage Ride Through

Introduction

Owing much to the production tax credit of $.021/kW-hr, the U.S. wind industry set records for installed capacity in 2008 by installing over 8000MW of new capacity. However, the year of 2009 began with much uncertainty for the industry, as it was facing difficult financing issues along with the uncertainty of an expiring tax credit. Then the passage of the American Reinvestment Recovery Act (ARRA) revitalized the industry as it provided for new tax grants. These new grants provided for as much as 30% of the project’s capital investment (in lieu of a production tax credit). So by the end of 2009 the U.S. wind industry set yet another record with about 10,000MW of new power capacity in the U.S. These generation additions were second only to natural gas [1]. And so for the past few years the U.S. wind industry has been growing at an annual rate of about 39%, and now the industry is commonly installing utility-scale generation plants of 100MW and larger. With more penetration of these renewable resources, it is becoming more important to transmission system operators that these new plants meet or exceed requirements for maintaining utility power quality.

Pictured is the Iberdrola Wind Plant in Atchison County, Missouri

Types of Wind Turbine Generators

Typically wind turbine generators do not utilize conventional line-connected synchronous machines, but rather other machine designs. The evolution of the wind turbine design has allowed for the capture of greater power over more variable wind conditions. The type of wind turbine generator is important in evaluating their power quality characteristics. The WCC was instrumental in developing various stability models, where different wind turbine types were introduced [2].

The Type 1 Wind Turbine Generator (WTG) is shown in Figure 1. It utilizes an induction motor. It operates near synchronous speed, with a minor amount of speed variation from the slip of the motor. The operation of this machine has been described as being like “blowing on a fan”. The Type 1 WTG induction generator will always consume VARs, so it is accompanied with power factor correction. These power factor correction units are an important resonance consideration when a harmonic study is performed.

Figure 1 – Type 1 Wind Turbine Generator

The Type 2 Wind turbine generator is shown in Figure 2. In this case a wound rotor induction generator is utilized. The rotor terminals are brought external to the motor via slip rings, and the rotor resistance is controlled. This configuration allows a higher slip and a wider speed control range than available with the Type 1 WTG.

Figure 2 – Type 2 Wind Turbine Generator

The Type 3 wind turbine generator (Figure 3) is also commonly referred to as the Doubly-Fed Asynchronous Generator (DFAG) or as a Doubly-Fed Induction Generator (DFIG). In this configuration the rotor is separately powered through a double-conversion power electronic bridge. The power delivered by the machine is the net result of both power circuits. The advantage of the Type 3 wind turbine is controllability of the machine over a wide-speed range, and the ability to control power factor from leading to lagging as required by the grid. Typically, the power conversion in the rotor circuit is about 30% of the overall capacity of the machine.

Figure 3 – Type 3 Wind Turbine Generator

The Type 4 wind turbine (Figure 4) generator utilizes full power conversion via voltage source inverters. The generator operates at the mechanical optimum speed, while the inverters convert the power back to line frequency.

The inverters utilize PWM style controls, so that the current harmonics to the grid should be low (Ithd<5%).

Figure 4 – Type 4 Wind Turbine Generator

Harmonics Issues of Wind Power Plants

The Type 1 and Type 2 wind turbines are not harmonic current sources, but resonance issues are still a concern. Utility scale wind power plants typically utilize underground cable collector systems. These systems typically can utilize 50 miles of underground cable, where the total charging current can be 10MVAR. Additionally, Type 1 and Type 2 turbines will require substation capacitor banks in addition to the turbine power factor correction. All of these system capacitances combine with the system inductance to form resonance concerns. In some plants the capacitor banks have experienced failures due to high amount of harmonic currents being absorbed from system background harmonic levels.

Type 3 and Type 4 wind turbines utilize power electronics, but the voltage source inverter technology should provide for a relatively low amount of current harmonic distortion (Ithd<5%). Often the PWM switching frequency (<1kHz) provides for the highest harmonic component of the current distortion. Generally these higher order harmonics (<20th) are at dispersed phase angle representations, so that the net affect of many turbines is minimal. As with the turbines discussed in the paragraph above, most of the harmonics issues will be associated with the resonance of the collector system cables, and other reactive power support (when required).

Flicker at Wind Power Plants

Some minor power pulsations can introduce flicker power (voltage fluctuation caused by real and reactive power changes) from wind turbine generators. Additionally, cut-in and cut-out switching operations can introduce flicker, and these issues (along with voltage regulation) have to be studied very carefully for dispersed applications where single wind turbines are installed on a distribution system.

However, for utility scale wind power plants, flicker has not been a concern. The high short circuit levels of the transmission system interconnection, along with the diversity of several turbines operating independently, have been enough to minimize the concern of flicker for large wind power plants.

Overvoltage/Grounding Considerations of Wind Power Plants

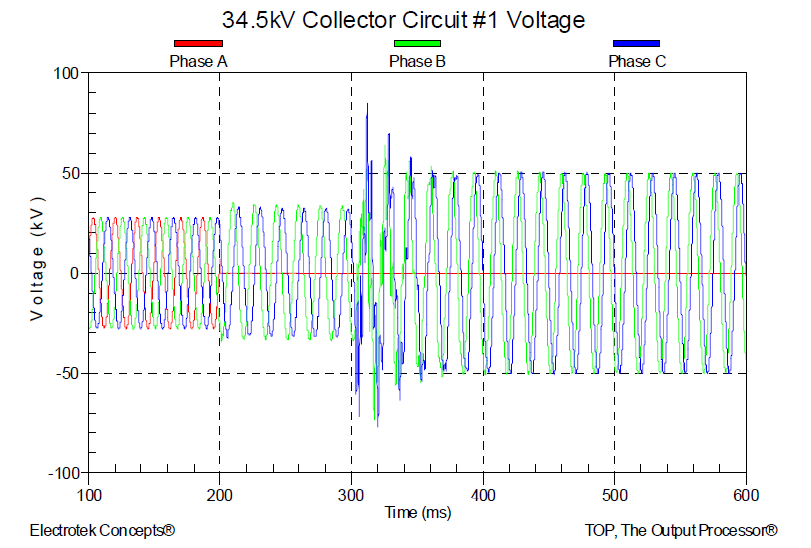

Wind turbine generators, usually connected by delta-wye transformers from the 34.5kV collector system to the generator operating voltage (often 575V or 690V), do not provide their own ground source. Separate grounding transformers are usually provided on each of the 34.5kV collector circuits to provide a ground source for the condition of a single-line-to-ground fault. Following the fault, after the collector system breaker clears the fault, the circuit becomes isolated and is powered only from the wind turbines. The grounding transformer provides a fault current path and also limits the overvoltage condition on the feeder. Figure 5 below is a PSCAD/EMTDC simulation of the collector system voltage during a fault and after the clearing operation of the substation breaker.

Figure 5 – PSCAD/EMTDC Simulation Result of Fault on 34.5kV Collector Circuit

Care must also be taken to insure that the transmission feed from a wind plant is grounded under various contingencies, otherwise the self-excitation of the feed from the wind turbine generators could similarly develop large overvoltage conditions, which can arise in only a few cycles. If the system is not properly grounded, these conditions can easily overwhelm the temporary overvoltage (TOV) ratings of surge arresters.

Other Interconnection Requirements of Wind Plants

Large utility-scale wind power plants are now commonly 100MW or larger. And the total penetration of wind power is becoming 10-20% in some regions (on windy days!). Accordingly, the FERC Order 661-A (2005) addressed wind power plants setting forward some requirements for reactive power, ride through capability to maintain operation during nearby fault events, and also for the sites to have two-way SCADA capabilities as required by the transmission system operator.

Initially, wind power plants with type 1 and type 2 turbines were consumers of reactive power. When the amount of wind power was relatively small, the plants could be given special treatment. Nowadays, utility-scale wind power plants are expected to act as “grown ups”, and do their part in providing reactive power. The most common requirement is for the wind plant to be able to operate at 0.95 leading and lagging. Some facilities are even required to put in dynamic reactive power control if the need is demonstrated by a study.

In the U.S. a common requirement is now for Zero Voltage Ride Through (ZVRT) for a three-phase fault for 9 cycles (0.15sec), however these requirements are relaxed for turbines installed before 2008, requiring LVRT to 0.15pu voltage for 9 cycles. Some regions have also begun to adopt overvoltage ride through recommendations for turbine wind plants.

Example Evaluation of the IEEE 519 Recommended Limits for Harmonics

Transmission system operators are requiring in their interconnection agreements with wind plants that the facility meet the harmonic limits of the IEEE Std. 519 (1992) “Recommended Practices and Requirements for Harmonic Control in Electric Power Systems”. The standard has two types of harmonic limits:

Harmonic Voltage Distortion Limits – These are often described as “utility” requirements where the grid operator must enforce the necessary current limits, and limit resonance concerns and network weakness in order to meet the maximum voltage distortion limits. The limits of Table 1 below are quite restrictive for transmission systems above 161kV.

Table 1 – IEEE 519 Harmonic Voltage Limits

| Bus Voltage | Maximum Individual Harmonic Component | Maximum THD |

|---|---|---|

| 69 kV and below | 3% | 5% |

| 115 kV to 161kV | 1.5% | 2.5% |

| Above 161kV | 1.0% | 1.5% |

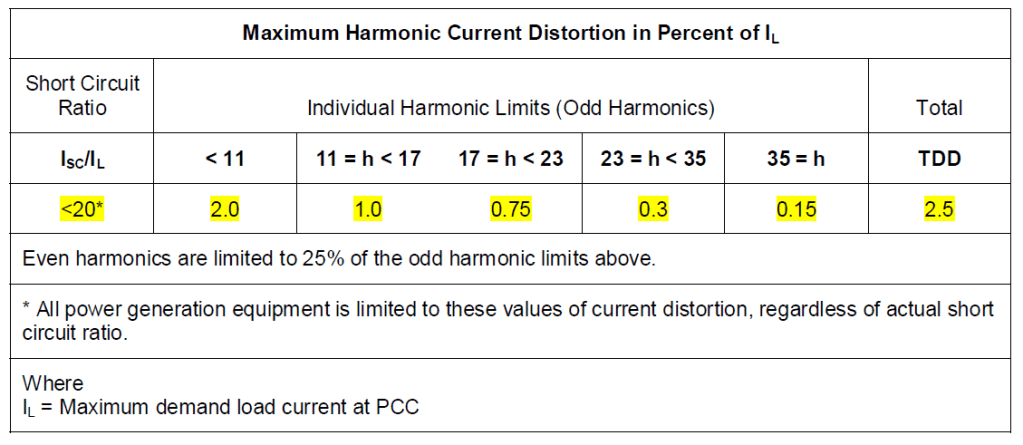

Harmonic Current Limits – These limits are applied to the currents at the point of interconnection. The short circuit ratio is irrelevant in this case, as the standard stipulates that power generation equipment must meet the most stringent limits. The standard provides the limits as a percentage of IL, the maximum current. For example each of the lower order harmonic currents must be no more than 2% of the maximum current.

Table 2 – IEEE Harmonic Current Limits for Wind Plant Connections above 69kV

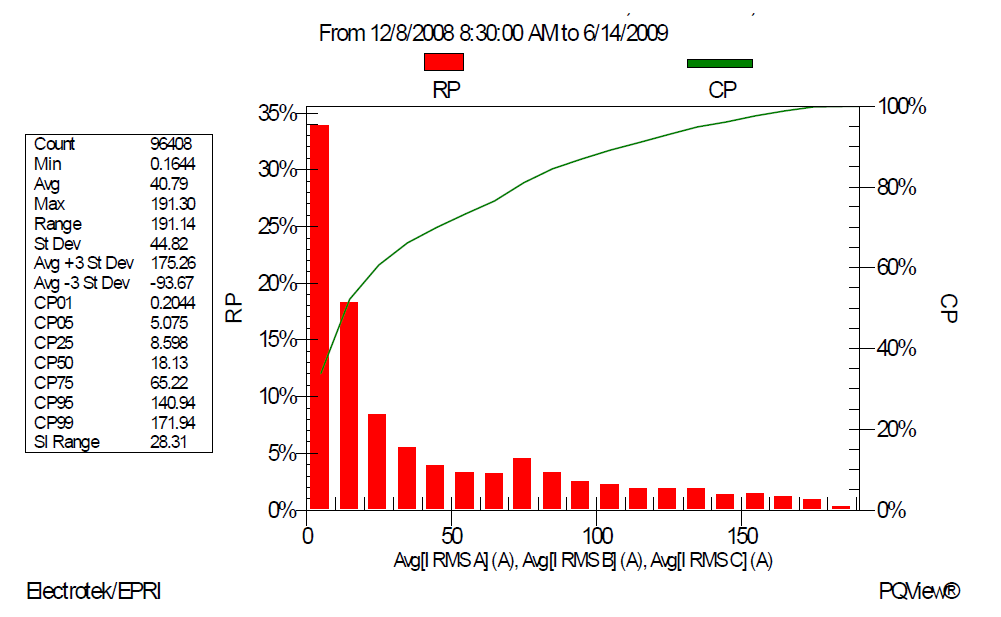

So, in order to determine the harmonic currents compliance with IEEE 519, the maximum current IL must be determined. It could be plant’s full production rating (perhaps at 95% power factor). It is probably more properly determined by the maximum measured current, determined by the statistical analysis as the CP 99%, where CP stands for “cumulative probability” and CP99% is the value that exceeds 99% of measured load current. For example, in Figure 6 below the statistics data block shows that the CP 99% value is 172A, so IL = 172 A.

Figure 6 – Statistical Analysis of the Total Wind Plant Maximum Current

Once the maximum current, IL , is determined, then the percentages of Table 2 can be used to establish harmonic current limits at the individual harmonic frequencies, and also for the total harmonic current:

Next, the measured harmonic currents are statistically summarized and then compared against the limits.

Figure 7 – Trend of the Measured 5th Harmonic Current

Statistical summaries of the measurements are important. Figure 7 above shows a typical trend, where certain system transient conditions caused the measured harmonic current to be above the limit of 3.4 amps. However, when the data is statistically analyzed (Figure 8), it is found that the CP95% (cumulative probability value that exceeds 95% of the measured values) is 1.3 amps, which is well below the recommended IEEE 519 harmonic current limit.

Figure 8 – Statistical Summary of the Currents at Various Harmonic Frequencies

References

[1] American Wind Energy Association, http://www.awea.org

[2] IEEE Std. 519-1992 IEEE Recommended Practices and Requirements for Harmonic Control in Electrical Power Systems.

[3] IEEE 1453-2004 IEEE Recommended Practice for Measurement and Limits of Voltage Flicker on AC Power Systems.

[4] “Development and Validation of WECC Variable Speed Wind Turbine Dynamic Models for Grid Integration Studies”, M. Behnke, A. Ellis, Y. Kazachkov, T. McCoy, E. Muljadi, W. Price, J. Sanchez-Gasca, AWEA Windpower 2007.

[5] Characteristics of Wind Turbine Generators for Wind Power Plants, IEEE PES Wind Plant Collector System Design WG, IEEE PES General Meeting, Calgary 2009.

[6] FERC Order no. 661-A, “Interconnection for Wind Energy,” Docket No. RM05-4-001, December 2005.

Biography

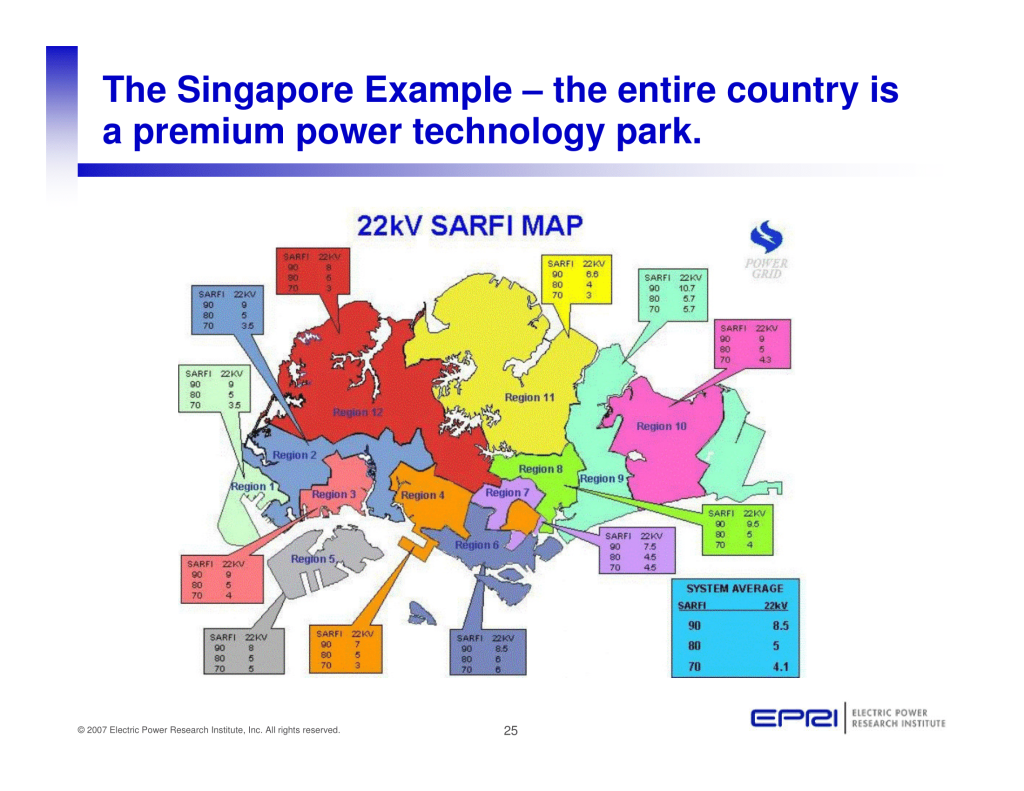

David Mueller is Manager of Power System Studies with Electrotek Concepts, Inc. in Knoxville, Tennessee. Dave consults on projects to study and solve power quality problems for industrial, commercial, and utility clients. He worked from 1993-1995 in Nottingham, England, starting the Power Quality Services group for East Midlands Electricity. At that time, he developed the 10-volume set of Power Quality Training Manuals. From 1998-2001 he assisted PowerGrid Ltd. in Singapore to develop their power quality capabilities. He has also worked with utilities in the US, Canada, Ireland, Brazil, China, and Malaysia. Recent projects have included studies on utility power quality compatibility levels, power system harmonics and filter designs, voltage sag mitigations, and high reliability data center power issues. Dave has a B. S. in Electrical Engineering from the University of Cincinnati and a Master of Engineering from the Electric Power Engineering Department at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute. He is registered as a Professional Engineer in the State of Ohio.