PQSynergy™ is an international forum to share experiences, requirements, questions, information, customer requirements, problems and solutions in the fast growth area of quality of supply requirements of sensitive loads, energy conservation and management and power quality monitoring and solutions.

For more information, you can visit the website: www.pqsynergy.com

View and download papers:

| PQSynergy™ Papers | Publishers |

|---|---|

| Advanced Biomass Gasification Solution | Lim Keng Hock, COMINTEL GREEN TECHNOLOGIES |

| Assessment Techniques for Evaluating Black Boxes Technologies | Bill Howe, PE, CEM, Program Manager, Power Quality Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) |

| Considerations as to what’s going to happen with all the data from SmartGrid | Wieslaw Jerry Olechiw, VP of International Sales and System Sales Dranetz and Electrotek Concepts |

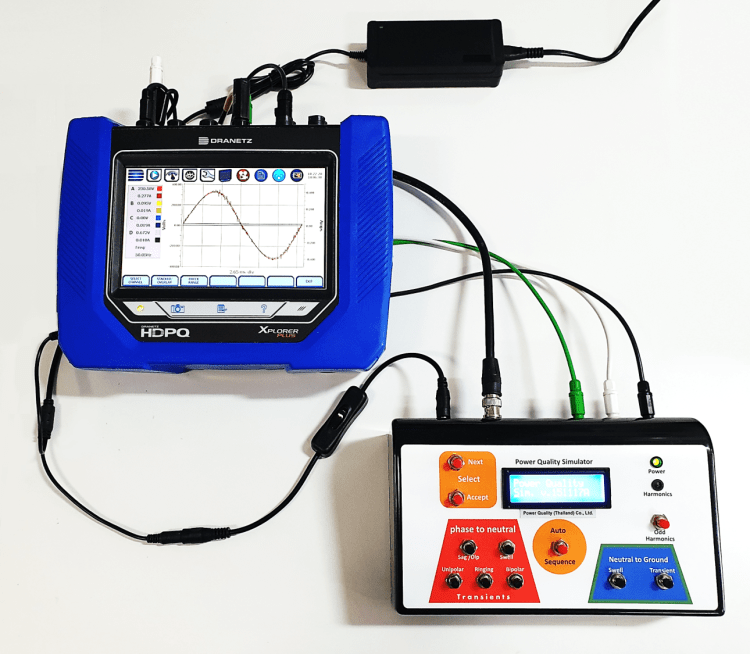

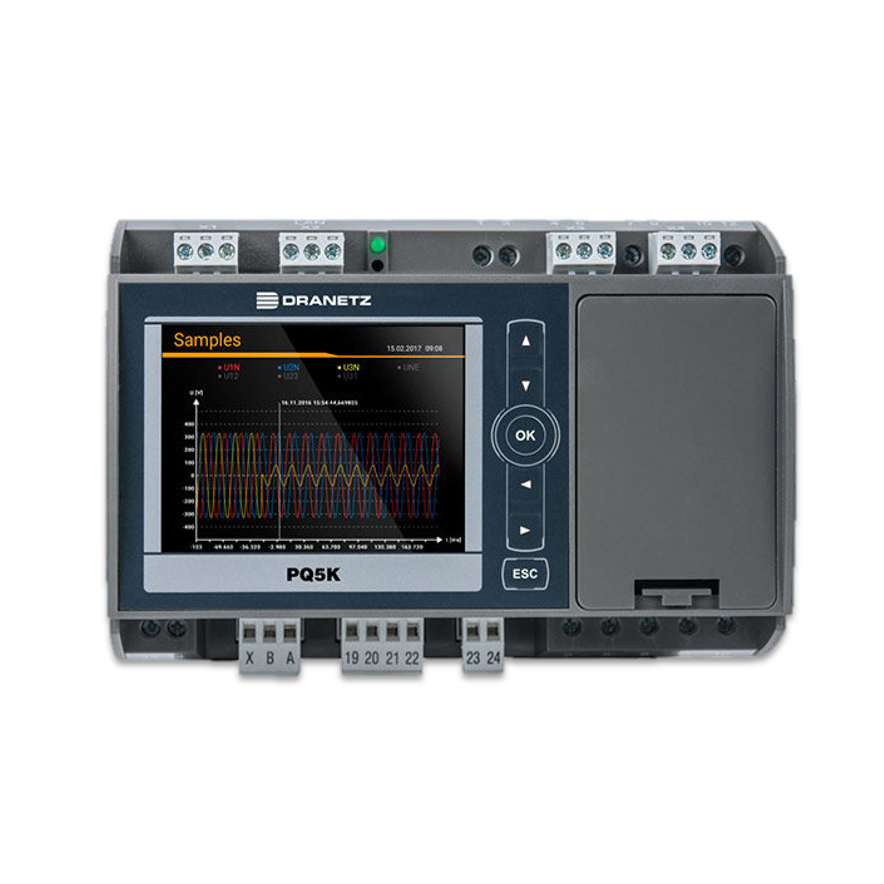

| Dranetz Industry Leading Portable Products | Wieslaw Jerry Olechiw, Vice President of International Sales Dranetz and Electrotek Concepts |

| Moving from Risk Assessment to Asset Management to Asset Optimization | Eric Stojkovich, Power Quality Thailand LTD |

| Sarawak Energy’s New Low Energy HQ Building | Gregers Reimann, MD IEN Consultants |

| The Evolution of System Protection Schemes for the Sarawak Power System | Victor Wong, Sarawak Energy Berhad |

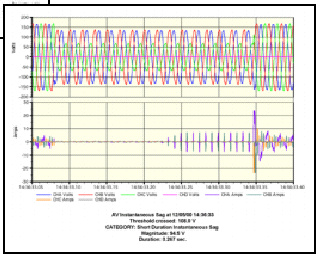

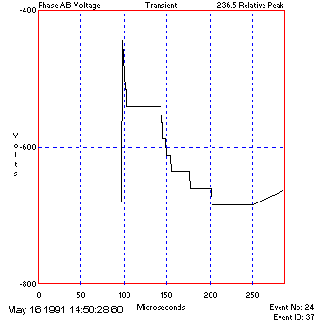

| The History of Power Quality Monitoring | Robert Moore |

| Voltage Quality and Power loggers | Power Quality Thailand LTD |

| Advances in Energy Efficiency Technologies and Impact on Power Quality | Terry Chandler, Power Quality Inc USA/Power Quality Thailand LTD |

| Household Load Characteristic for Harmonic Study | Panida Boonyaritdachochai, Power Quality Thailand LTD |

| Introduce Some New Power Quality Situation or Update in China | Qianlu Yan, Vice General Manager, Beijing Joint Harvest S&T Co., Ltd. |

| New Applications in Power Quality Monitoring and Analytics for T&D System | Doug Dorr, Electric Power Research Institute, Manager r – Advanced Monitoring Applications Group |

| Power Quality in Metering | Ming T. Cheng, Directory of Asian Operations |

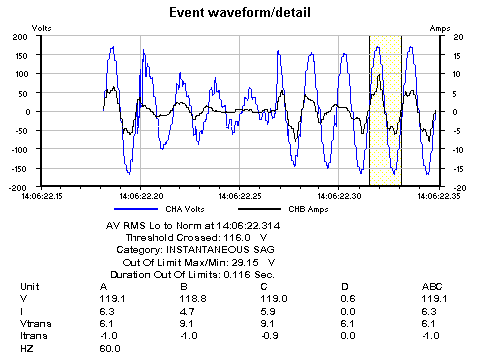

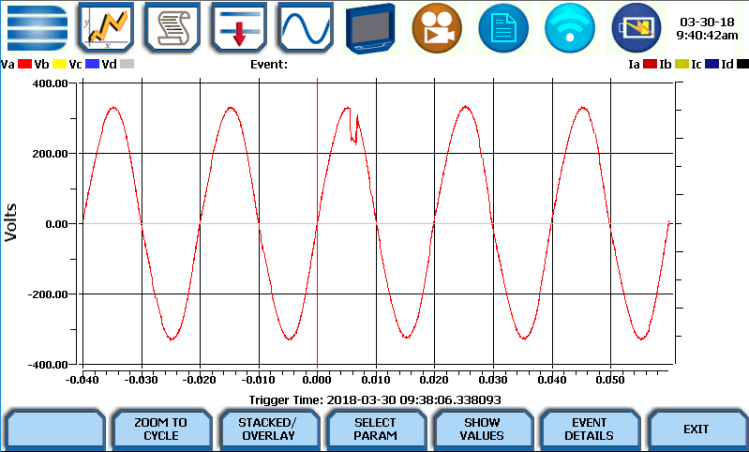

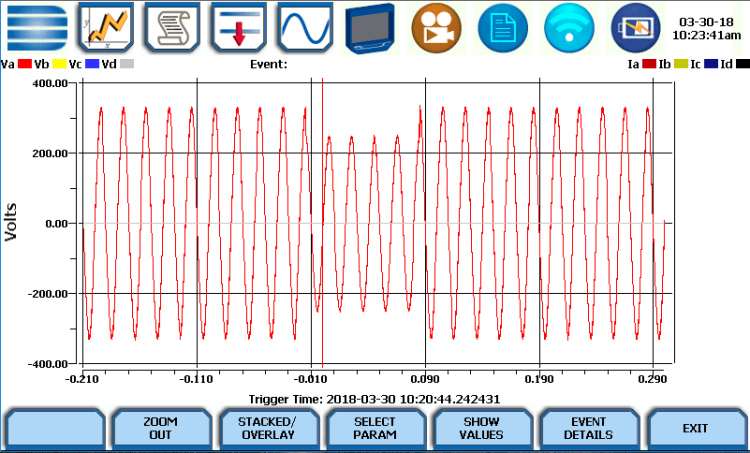

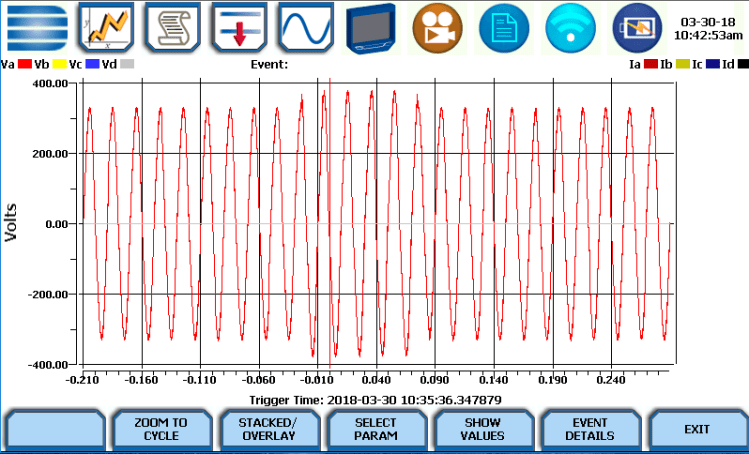

| PQ for Equipment Assessment and Incipient Failure | Bill Howe, PE, CEM, Program Manager, EPRI Power Quality Manager, EPRI Industrial Center of Excellence |

| Transients and Power Quality Issues in Domestic UPS especially in India | A.D.Thirumoorthy, Member, APQI |

| Benchmarking PQ Performance in the Era of the Smart Grid | Bill Howe, PE, Electric Power Research Institute Program Manager, Power Quality |

| New Technology for Stray and Contact Voltage Detection | Doug Dorr, Electric Power Research Institute, Manager r – Advanced Monitoring Applications Group |

| Powering the Next Generation of Metering Communications | Kerk See Gim, Power Automation |

| PQView Expanding into Grid Operations | Wieslaw Jerry Olechiw, Vice President of International Sales Dranetz and Electrotek Concepts |

| The Architecture of System Protection Schemes (SPS) Implemented in the Sarawak Power System | Ling Lee Eng, Sarawak Energy Berhad |