Published by Damian GŁUCHY1, Grzegorz TRZMIEL2, Poznan University of Technology

ORCID: 1. 0000-0003-2725-2614; 2. 0000-0002-3622-8889

Abstract. In the following article the impact of power characteristics of wind turbines on the total amount of generated power is introduced. The review of scientific literature suggested the need of further analysis of this issue. In order to do so, the performance parameters of eight wind turbines, 3kW each, were catalogued, their operational characteristics modeled, with the inclusion of sample measurements of essential environmental parameters, which were taken in exemplary location in Poland. Thanks to the gathered data, not only the wind speed histograms were made, but also the average wind speeds in particular months were calculated. Then, simulation studies were carried out to determine the most optimal wind turbine for a given location. The annual maximum amount of generated power served as the main criterion in the selection process. (Analiza wpływu charakterystyk mocy turbin wiatrowych na ilość wytwarzanej energii)

Streszczenie. W artykule przedstawiono wpływ charakterystyk mocy turbin wiatrowych na całkowitą ilość wytwarzanej mocy. Przegląd literatury naukowej wskazywał na potrzebę dalszej analizy tego zagadnienia. W tym celu skatalogowano parametry pracy ośmiu turbin wiatrowych o mocy 3kW każda, zamodelowano ich charakterystyki eksploatacyjne, uwzględniając przykładowe pomiary istotnych parametrów środowiskowych, które wykonano w przykładowej lokalizacji na terenie Polski. Dzięki zebranym danym wykonano nie tylko histogramy prędkości wiatru, ale również obliczono średnie prędkości wiatru w poszczególnych miesiącach. Następnie zrealizowano badania symulacyjne, które przeprowadzono w celu określenia najbardziej optymalnej turbiny wiatrowej dla danej lokalizacji. Głównym kryterium w procesie selekcji była roczna maksymalna ilość wytworzonej mocy.

Keywords: Wind turbine; Power characteristics modeling; Wind speed histogram; Wind turbine simulation.

Słowa kluczowe: turbina wiatrowa; modelowanie charakterystyk mocy; histogram prędkości wiatru; symulacja turbiny wiatrowej.

Introduction

Wind turbines, commonly referred to as wind generators are the type of the device which allows to transform the kinetic energy of wind into mechanical movement of turbine blades of the generator, creating electric energy as a result. Even though, the wind energy might seem to be wildly available, not every single corner of the Earth offers optimal conditions for the effective production of electric energy. Its total amount highly depends on various technical, performance parameters of the wind turbine and environmental conditions of the location, where the wind generator is placed. Only the proper analysis and mutual correlation of these factors can assure the quick return of incurred costs of the investment. This is especially important in the context of the use of wind turbines in distributed systems with energy storage, where implementation costs are significant. By appropriately matching the analyzed turbines to the location, the payback time for investment costs decreases, which allows to improve the profitability of the investment. In the case of investments in which energy storage and flexibly integrated renewable energy sources are used, it is the optimal selection of wind turbines that can bring the greatest savings to the overall economic balance. The best possible current use of electricity generated by wind turbines allows to limit the required capacity of energy storage, thus reducing investment and service costs. This is why the authors take up this problem as an important element of designing larger distributed systems for generating energy from RES with the possibility of its storage.

Many scientists try to precisely determine the performance parameters of the currently applied solutions worldwide [1-3], in terms of their cost-effectiveness in the field of wind energetics. Some e.g. [4, 21] tackle issues of strictly mechanical nature like selecting optimal machinery and the optimal adjustment of its parameters. Different solutions or propositions of update of the wind turbinecontrolled systems can be found in various publications [5- 10]. Nowadays, scientific research [11, 12] is more attentive to the problem of dispersion and diversification of wind sources in relation to maintaining stability and safety of the system designed to generate electric energy, as well as the need for analysis of potential damage of individual parts of the system e.g. planetary gears [13] or turbine blades [14, 15]. Ongoing tests of various [16, 17] with propositions for optimal energy storage solutions [18-20, 23]. It is worth noting that in the analyzes of the operation of wind turbines in specific wind conditions, histograms of wind speed and / or directions are often used [41, 43, 45, 46, 50]. A popular mathematical tool used to analyze the histograms of wind speed and generated energy is the Weibull distribution [42, 45, 46, 50, 51, 52, 53, 54, 55]. As can be seen, it is used for a variety of analytical tasks aimed at calculating current parameters, but also in modeling and predicting the operation of wind turbines and their components, often taking into account the stochastic nature of the processes taking place [52, 54, 55]. Histograms are also used e.g. in the analysis of vibrations of components of wind turbines, eg blades, in search of failure causes [44, 49] and in the modeling of wind conditions [47, 48]. All these actions are aimed to improve electric efficiency of the wind turbine system, its profitability and the reduction of time, necessary to return incurred costs of the investment.

The authors reviewed, among others of the abovementioned scientific articles, selectively used the tools and mathematical methods used there, and proposed an original procedure for solving the problem covered in the topic of the article for an example location in Poland. The authors of the following article decided to investigate the problem of selection of optimal wind turbines with different characteristics of power, currently available in retail. In order to maximize the amount of generated electric energy, various location types were taken into account, as shown in [22], not to mention the overall stability of wind conditions in a particular area. These aspects had to be taken into account to obtain accurate calculations regarding the maximum amount of generated energy [22] especially if such external factors always have the impact on the total amount of generated energy. Therefore, proper methodology to investigate the problem of optimization further were introduced, along with results of simulation research. The conducted research allowed to make the most optimal choice of specific solutions in different work conditions.

Generation of energy in wind turbines

1.1. Location conditions

Before any wind turbine is considered as a viable source of electric energy, first of all the location conditions had to be analyzed with a great caution due to their impact scale on the entire investment e.g. wind speed and its stability, because they are going to affect the performance of every wind turbine. Such analysis needs to include not only atmospheric conditions and latitude, but also factors which are not directly connected with climate, nor latitude. One of those factors is the ability to generation of heat and its later dissipation by seas and lands. It impacts the creation and movement of air masses. Topographic relief is important as well and must not be overlooked, due to its involvement in various orographic changes; e.g. mountain ranges, valleys or rivers. Vegetation might not be an orographic factor, but it has to be taken into the equation, because of its impact on the strength of wind. For instance, forest landscapes cause air distortions in the movement of air masses, while areas with less greenery do not exhibit create such distortions. The latitude itself determines so-called “latitude class”, which significantly impacts the amount of generated energy by wind turbines.

The characteristics of wind conditions of a particular locations can be achieved by measuring the speed and the direction of wind in specified time, it is highly advised to not take shorter period than one year in calculations. It allows to estimate the average wind speed and its stability in general. One must remember that these type of calculations must be conducted on 10 meters above the sea level. The wind speed differs, depending on the attitude where measurements are taken, therefore, all calculations are described by the function [24], where the measurement of the attitude hp in relation to the ground level must be conducted in a direct correlation to attitude of the turbine rotor ht.

where: α – latitude[-], vp – wind speed, where the measurement takes place hp [m/s], vt – wind speed on the attitude ht [m/s].

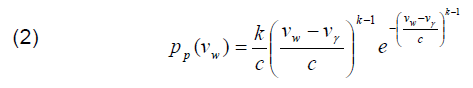

The change of wind speed is stochastic and its value heavily depends on atmospheric conditions, which makes the momentum difficult to utilize efficiently on a large scale. Even the analysis of multiple, annual measurements does not allow to make accurate estimation of average wind speed in later time periods with sufficient precise, Therefore, in the process of making the characteristics of energetic properties of wind, the Weibull distribution is used as a density function, which allows for the “probable” estimation of wind speed [25]:

where: pp(vw) – probable density [-], k – dimensionless shape factor (k>0) [-], c – scale factor (c>0) [-], γw – shift factor (in case of wind speed – γw=0)[-]).

The stochastic nature of generation of electric energy from wind turbines practically prohibits the effective utilization of wind energy in autonomous sources, connected to the receiver. It is a result of the lack of correlation between the energy demand and its later utilization. Therefore, wind turbines are often used with electro energy system, allowing to minimize the instability of power generation if the ratio of generated power by the wind turbine between the power of electro energy system is miniscule [26]. Alternatively, it is possible to assume the cooperation of wind farms with energy storage and optionally with other renewable energy sources, which is more and more common with distributed generation of electricity. In this case, the idea presented by the authors of this article does not change, namely the optimal use of the energy generated on a regular basis by the power plants allows to reduce the target capacity of the designed energy storage. Due to the complexity of this issue, this topic is beyond the scope of this publication. However, it should be remembered that the topic proposed by the authors is important both in systems without and with energy storage. Apart from its stochastic nature, wind energy also has a deterministic component related to periodic changes: day, seasons of the year and multi-year period. The first two cases can be considered by analyzing the measurements of wind energy resources separately for the spring-summer and autumn-winter periods, and by determining the average difference in wind energy for night and day. The multiple annual period is the most difficult to take into account due to the need to have detailed speed measurements for a specific location from many years. Regardless of the type of the determined deterministic component, the measurements must always be performed with a frequency sufficient to analyze the dynamics of wind energy changes.

1.2. Technical parameters of wind turbines

The performance parameters of the wind turbine define the final shape of the characteristics of power generation and its high dependence on the wind speed. Its nonlinear operation is a result of partial suppression of the flow of the stream of air which decreases energy generation and the speed of the wind; described in the following equation [27]:

where: Pt – mechanical power of the wind turbine [W], Pw – the power in the stream of air [W], cp(λ) – Betz factor, which serves as sort of correction of the theoretical value – tip-speed ratio. λ [-].

The power of the air stream can be described with the following equation [28]:

where:, ρ – density of air [kg/m3], A – the surface area with the inclusion of blade coverage surface of the wind turbine [m2], vw – wind speed [m/s]. The tip-speed can be described with the following equation [29]:

where: ω – angular velocity of the turbine rotor [rad/s], R – the rotor radius [m].

The Betz factor in the function describes the tip speed for various wind turbine rotors is shown in Figure I. Its maximal value never exceeds 0.6, which is caused by various states of aerodynamic, based on the construction of the particular wind turbine e.g. number of blades or shape of the rotor itself.

The above values are strictly theoretical, therefore, it is advised to use the characteristics provided by the manufacturer of the wind turbine which should be included in catalog in the form of a table. It is a result of the measurements conducted on an actual location.

2. The analysis of wind conditions of a selected location regarding the usage of wind turbines

The analysis of a selected location was started 30 kilometers from the Rzeszow city in Poland, and naturally all kinds of orographic conditions had been taken into account in order to accurately determine wind conditions within the selected area. The measurements are taken from the database of the private owner of the wind turbines who agreed to use it in the publication. To do so, the average wind speed for each month had to be measured with a time step of 47 seconds (one year, 2011). The research was conducted in an ongoing manner on the height of 10 meters, allowing the creation of the detailed database, which included many useful parameters such as: date, time, average speed, atmospheric pressure or wind direction and its temperature. The gathered information was further analyzed, which was crucial to obtain accurate calculations regarding the average wind speed for every month of the year (shown in Figure 2), not to mention the average wind speed for as a whole, which equaled 5.7 m/s.

These analysis allow for the perinatal determination of wind conditions (capabilities) of the selected area, however, they do not provide any kind of feedback about the turbine type, which would be optimal for a desired area. Therefore, the next step was to pinpoint the frequency distribution of the particular wind speed. It was achieved by making a histogram, which is the density of probability of particular wind speed to occur – created by summing up 47 second wind events of particular strength e.g. for 1 m/s, the range between 0.5 to 1.4 m/s was taken into the equation.

Instead of a detailed showcase of the database of wind speed which is not only quite vast, but also difficult to analyze, it is better to describe wind conditions by a histogram. Such approach allows to select the optimal type of wind turbine much quicker. In order to make the whole process of modeling wind conditions even more effective, the Weibull function can be used to reduce the necessary calculations [31]. Such calculations were made for the histogram of wind speed, which was based on individual calculations, done by the authors of the following article; as shown in Figure 3.

3. Modeling of selected wind turbines

The determination of the wind turbine models was performed in the MS Visual Studio environment. It involved the implementation of eight wind turbines from different manufacturers with a power of 3 kW each, in table form with a time step for every 1 m/s. The following information was obtained from catalog notes from the websites of individual producers [32 – 39]. Visualization of individual power characteristics is presented in Figure 4.

The selected cases for the database include both turbines with vertical and horizontal rotor axis of rotation. At the same time, it is important to emphasize the confusing “diversity” in terms of interpretation of technical parameters by the manufactures of wind turbines. The rated power of the turbine is usually the maximum power achieved at a certain wind speed, kept to the cutout speed, as shown in various scientific publications. However, most manufactures give only approximate values. In all investigated cases, the value of generated power by the turbine was much higher than the one given by the manufacturer (3 kW). (by several, or even several dozen percent). In addition, in their catalog notes focus on presenting the slope of the characteristic of power rise, ignoring the behavior of the generator when it exceeds the rated power speed. In this area, turbines are often subjected to decelerate artificially. The generated power decreases when the wind power is increasing.

Power characteristics are given by manufacturers usually in a tabular form, with a wind speed step every 1 m / s. In order to obtain continuity of these characteristics, the least approximation of squares was used with the exponential function [40]. This allowed to achieve the so-called “golden mean” between the accuracy of calculations and the time necessary to obtain them.

4. Simulation of work of modeled wind turbines in the conditions of the tested location

The simulation of modeled wind turbines was performed by using two methods: based on a wind speed histogram and directly using wind speed measurements from a database. In both cases, it was necessary to take the height of the mast into account, which was made by using the vertical wind profile [22,24] described in formula 1.

The simulation based on the wind histogram was performed by searching for the best possible correlation between the production characteristics and the wind speed histogram. The generator is selected in a way that its characteristics of Pel=f(vw), could coincide with the most common wind speeds. From the simulation point of view, an algorithm was created, which showed the percentage annual share of rated power of the turbine, based on the wind histogram and modeled characteristics of wind turbine. On its basis, the average annual amount of produced energy was determined. Both of these values for individual wind turbines are presented in Table 1 (column 3 and 4). The highest value of generated energy indicates the best adjustment of the turbine parameters in relation to wind conditions in a particular location. At the same time, it should be noted that selecting the most optimal solution is burdened by the potential error, which is a result of rounding the numbers used to create the histogram. In case of the application created by the authors to determine the probability of speed occurrence, e.g. 1 m/s, all cases of speed occurrence in the range from 0.5 m/s to 1.4 m/s inclusive are included.

A much more accurate value of energy obtained from a wind turbine can be obtained by using the power characteristics and wind speed samples in the simulation. Accuracy can be additionally increased if the averaging time ΔtTW for one sample is as short as possible. The amount of ATW electricity generated by a specific type of wind turbine was determined from the dependence 6. The results of the simulation were also presented in Table 1 (column 2).

where: N – number of measurement samples, PTW(vw) – wind turbine power for the n-th measurement sample (wind speed is equal to vw)[W], ΔtTW – time step for measuring wind speed [s].

Table 1. Average annual energy value generated on the basis of power characteristics by wind turbines of various manufacturers [own study]

From the analysis of the results presented in Table 1, it can be concluded that the average annual energy yields obtained by the two simulation methods described above are very similar. This means that for a given location, the turbine which generates the highest power can be selected, based on the wind speed measurement and the histogram. The second of these methods is much simpler to implement, due to the use of wind speed probability distribution rather than an extensive measurement database. From the point of view of the algorithm, it is also much faster due to the smaller number of operations performed. In the presented location, the best in 2011 would be BOF-V turbine with its power of approx. 30%, provides a satisfactory result.

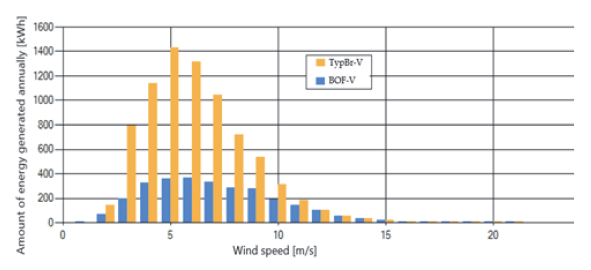

In extreme cases: the best and worst correlation between wind power and speed characteristics shows a 60% difference in terms of generated electricity. The reason for such a large discrepancy in annual energy yields can be presented in the form of a graph of the amount of energy generated annually in given wind speed ranges, as shown in Figure 5. This disproportion indicates the importance of earlier analysis of wind conditions in correlation with the characteristics of wind turbines.

5. Conclusions

Based on the research, modeling and simulation carried out, the authors analyzed the impact of wind turbine power characteristics on the amount of energy generated in a given location. The result is an unequivocal demonstration of the need to gather information about windiness and the environmental parameters of a particular location before investing in wind turbines. Such archived information should be saved in the form of a database or histogram of wind speed, for later processing with the participation of wind turbine power characteristics. Irrespective of the simulation method chosen from the two used by the authors, the amount of energy generated from each of the considered wind turbines can be obtained. Appropriate selection of wind turbines for the location allows to reduce the capacity of the designed energy storage in distributed generation systems containing integrated RES, thus reducing investment and service costs. Thus, the proposed subject of the article is universal, regardless of the target concept of a distribution network, including any generation systems and, optionally, energy storage.

Funding: This research was funded by Polish Government, grant number [0212/SPAD/0512].

Conflicts of Interest: The authors declare no conflict of interests.

REFERENCES

[1] Pfaffel S., Faulstich S., Kurt R., Performance and reliability of wind turbines: A review, Energies 10.11 (2017): 1904, https://doi.org/10.3390/en10111904

[2] Hyeonwu K., Bumsuk K., Wind resource assessment and comparative economic analysis using AMOS data on a 30 MW wind farm at Yulchon district in Korea, Renewable Energy 85 (2016): 96- 103, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.renene.2015.06.039

[3] Garcia-Sanz M., A Metric Space with LCOE Isolines for Research Guidance in wind and hydrokinetic energy systems, Wind Energy 23.2 (2020): 291-311, https://doi.org/10.1002/we.2429

[4] Tafticht, T., et al., Output power maximization of a permanent magnet synchronous generator based stand-alone wind turbine, 2006 IEEE International Symposium on Industrial Electronics. Vol. 3. IEEE, 2006

[5] Morimoto S., et al., Sensorless output maximization control for variable-speed wind generation system using IPMSG, IEEE Transactions on Industry Applications 41.1 (2005): 60-67

[6] Errami Y., Ouassaid M., Maarouf M., Control of a PMSG based wind energy generation system for power maximization and grid fault conditions, Energy Procedia 42 (2013): 220-229

[7] Corradini M.L., Letizia M., Ippoliti G., Orlando G., Fully sensorless robust control of variable-speed wind turbines for efficiency maximization, Automatica 49.10 (2013): 3023-3031

[8] Yaramasu V., Wu B., Predictive control of a three-level boost converter and an NPC inverter for high-power PMSG-based medium voltage wind energy conversion systems, IEEE Transactions on Power Electronics 29.10 (2013): 5308-5322

[9] Gebraad P., et al., Maximization of the annual energy production of wind power plants by optimization of layout and yaw-based wake control, Wind Energy 20.1 (2017): 97-107

[10] Park J., Law K.H.. Bayesian ascent: A data-driven optimization scheme for real-time control with application to wind farm power maximization, IEEE Transactions on Control Systems Technology 24.5 (2016): 1655-1668

[11] Li X., Diversification and localization of energy systems for sustainable development and energy security, Energy policy 33.17 (2005): 2237-2243

[12] Liljenfeldt J., Pettersson O., Distributional justice in Swedish wind power development – An odds ratio analysis of windmill localization and local residents’ socio-economic characteristics, Energy Policy 105 (2017): 648-657

[13] Zhang Y., Lu W., Chu F., Planet gear fault localization for wind turbine gearbox using acoustic emission signals, Renewable Energy 109 (2017): 449-460

[14] Arnold P., et al., Radar-based structural health monitoring of wind turbine blades: The case of damage localization, Wind Energy 21.8 (2018): 676-680

[15] Park B., et al., Delamination localization in wind turbine blades based on adaptive time-of-flight analysis of noncontact laser ultrasonic signals, Nondestructive Testing and Evaluation 32.1 (2017): 1-20

[16] Campagnolo F., et al., Wind tunnel testing of a closed-loop wake deflection controller for wind farm power maximization, Journal of Physics: Conference Series. Vol. 753. No. 3. IOP Publishing, 2016

[17] Campagnolo, F., et al., Wind tunnel testing of power maximization control strategies applied to a multi-turbine floating wind power platform, The 26th International Ocean and Polar Engineering Conference. International Society of Offshore and Polar Engineers (2016)

[18] Tomczewski A., Kasprzyk L., Nadolny Z., Reduction of power production costs in a wind power plant–flywheel energy storage system arrangement, Energies 12.10 (2019): 1942

[19] Tomczewski A., Kasprzyk L., Optimisation of the structure of a wind farm—Kinetic energy storage for improving the reliability of electricity supplies, Applied Sciences 8.9 (2018): 1439

[20] Hemmati R., Technical and economic analysis of home energy management system incorporating small-scale wind turbine and battery energy storage system, Journal of Cleaner Production 159 (2017): 106-118

[21] Śliwiński A., Wróbel K., Tomczewski K., Tomczewski A., Impact of winding parameters of a switched reluctance generator on energy efficiency of a wind turbine, SME (2018), https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8442592, DOI: 10.1109/ISEM.2018.8442592

[22] Wrobel K., Tomczewski K., Sliwinski A., Tomczewski A., The Impact of a Wind Turbine Characteristics on the Annual Energy Performance at Given Wind Speed Distribution, PTZE (2018), https://ieeexplore.ieee.org/document/8503230, DOI: 10.1109/PTZE.2018.8503230

[23] Kasprzyk L., Tomczewski, A., Bednarek K., Bugała A., Minimisation of the LCOE for the hybrid power supply system with the lead-acid battery, In E3S Web of Conferences (Vol. 19, p. 01030). EDP Sciences, EEMS (2017), DOI: 10.1051/e3sconf/20171901030

[24] Błasiński W.. Simulator low-power wind turbine (in Polish), Przegląd Elektrotechniczny No. 12 (2017): 263-265

[25] Patel M.R.. Wind and Solar Power Systems: Design, Analysis, and Operation. Second Edition, Taylor & Francis Group (2006)

[26] Malko J., Prediction of wind farm generation capacity (in Polish), Przegląd Elektrotechniczny No.9 (2008): 65-67

[27] Uracz P., Karolewski B., Modeling of wind turbines with the use of power factor characteristics (in Polish), Prace Naukowe Instytutu Maszyn, Napędów i Pomiarów Elektrycznych 59 (2006), Wrocław: Wydawnictwo Politechniki Wrocławskiej

[28] Soliński I., Energy and economic aspects of the use of wind energy (In Polish), Wyd. Inst. Gospodarki Surowcami Mineralnymi i Energią PAN (1999), Krakow

[29] Jarek G., Jeleń M., Gierlotka K., Wind turbine simulator based on a DC motor (in Polish), Przegląd Elektrotechniczny (6), 2014

[30] Numerical Investigation of the Savonius Vertical Axis Wind Turbine and Evaluation of the Effect of the Overlap Parameter in Both Horizontal and Vertical Directions on Its Performance, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-8994/11/6/821/xml

[31] Kumar D., Chatterjee K., A review of conventional and advanced MPPT algorithms for wind energy systems, Renewable and sustainable energy reviews (2016): 957-970

[32] https://www.brasit.pl/turbina-wiatrowa-typbr-v-3kw/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[33] https://www.brasit.pl/aeolos-v-3000w/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[34] https://www.brasit.pl/pionowa-elektrownia-wiatrowa-buf-v-3kw/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[35] https://www.brasit.pl/pionowa-elektrownia-wiatrowa-saw-v-3kw/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[36] https://www.brasit.pl/elektrownia-wiatrowa-turbina-hy-h-3kw/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[37] https://www.brasit.pl/elektrownia-wiatrowa-turbina-humbr-h-3kw/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[38] https://ekotaniej.pl/media/wysiwyg/karta-turbina.pdf (accessed 21.05.2020)

[39] http://hipar.pl/ecorote-2800/ (accessed 21.05.2020)

[40] Thapar V., Agnihotri G., Sethi V.K., Critical analysis of methods for mathematical modelling of wind turbines, Renewable Energy, vol. 36 (2011), no. 11, pp. 3166-3177

[41] Paulsen B.M., Schroeder J.L., An examination of tropical and extratropical gust factors and the associated wind speed histograms, Journal of Applied Meteorology 44.2 (2005): 270-280

[42] Carta J.A., Ramirez P., Velazquez S., A review of wind speed probability distributions used in wind energy analysis: Case studies in the Canary Islands, Renewable and sustainable energy reviews 13.5 (2009): 933-955

[43] Sohoni V., Gupta S, Nema R., A comparative analysis of wind speed probability distributions for wind power assessment of four sites, Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering & Computer Sciences 24.6 (2016): 4724-4735

[44] Joshuva A., Sugumaran V., A study of various blade fault conditions on a wind turbine using vibration signals through histogram features, Journal of Engineering Science and Technology 13.1 (2018): 102-121

[45] Sarkar A., Gugliani G., Deep S., Weibull model for wind speed data analysis of different locations in India, KSCE Journal of Civil engineering 21.7 (2017): 2764-2776

[46] Gugliani G. K., et al., New methods to assess wind resources in terms of wind speed, load, power and direction, Renewable Energy 129 (2018): 168-182

[47] Zárate-Miñano R., Anghel M., Milano F., Continuous wind speed models based on stochastic differential equations, Applied Energy 104 (2013): 42-49

[48] Chen X., Huang W., Yao G., Wind speed estimation from X-band marine radar images using support vector regression method, IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Letters 15.9 (2018): 1312-1316

[49] Yu Y., et al., Image-based damage recognition of wind turbine blades, 2017 2nd International Conference on Advanced Robotics and Mechatronics (ICARM), IEEE

[50] El-Asha S., Zhan L., Iungo G.V., Quantification of power losses due to wind turbine wake interactions through SCADA, meteorological and wind LiDAR data, Wind Energy 20.11 (2017): 1823-1839

[51] Sedaghat A., et al., Determination of rated wind speed for maximum annual energy production of variable speed wind turbines, Applied energy 205 (2017): 781-789

[52] Seo S., Si-Doek O., Ho-Young K., Wind turbine power curve modeling using maximum likelihood estimation method, Renewable energy 136 (2019): 1164-1169

[53] Soulouknga M. H., et al., Analysis of wind speed data and wind energy potential in Faya-Largeau, Chad, using Weibull distribution, Renewable energy 121 (2018): 1-8

[54] Asghar A.B., Liu X., Estimation of wind speed probability distribution and wind energy potential using adaptive neuro-fuzzy methodology, Neurocomputing 287 (2018): 58-67

[55] Horn J.T., Leira B.J., Fatigue reliability assessment of offshore wind turbines with stochastic availability, Reliability Engineering & System Safety 191 (2019): 106550

Authors: dr inż. GrzegorzTrzmiel, Politechnika Poznańska, Instytut Elektrotechniki i Elektroniki Przemysłowej, ul. Piotrowo 3a, 60-965 Poznań, E-mail: Grzegorz.Trzmiel@put.poznan.pl; mgr inż. Damian Głuchy, Politechnika Poznańska, Instytut Elektrotechniki i Elektroniki Przemysłowej, ul. Piotrowo 3a, 60-965 Poznań, E-mail: Damian.Gluchy@put.poznan.pl.

Source & Publisher Item Identifier: PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, ISSN 0033-2097, R. 98 NR 11/2022. doi:10.15199/48.2022.11.60