Published by 1. Diego GIRAL-RAMÍREZ1, 2. Cesar HERNÁNDEZ-SUAREZ1, 3. José CORTES-TORRES2,

Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia (1)

Universidad Industrial de Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia (2)

ORCID: 1. 0000-0001-9983-4555, 2. 0000-0002-7974-5560, 3. 0000-0001-9232-6785

Abstract. Distributed Generation (DG) is a small-scale technology linked to consumers through the distribution system and has a high potential for technical, economic, and environmental benefits. The incorporation of generation at demand points produces a variety of load flow and fault currents, changing unidirectional flows to bidirectional structures and altering the characteristics of fault currents. The traditional methods for fault location that are implemented correspond to the traveling wave method and the impedance method. DG inclusion establishes new challenges, so it is necessary to propose or adopt models that improve the location process. During the last years, several Artificial Intelligence (AI) techniques have been introduced, where it presents good results due to its high performance and capacity to provide a fast response. This paper reviews AI-based techniques for fault location in distribution networks with DG. Although the advances are promising, many questions still need to be answered; the permanent work is to identify the advances in AI to obtain better results. Additionally, the implemented strategies must be scalable to ease the computational load and to be able to solve problems of greater complexity.

Streszczenie. Generacja rozproszona (DG) to technologia na małą skalę powiązana z konsumentami za pośrednictwem systemu dystrybucyjnego, która ma wysoki potencjał korzyści technicznych, ekonomicznych i środowiskowych. Włączenie generacji w punktach odbioru wytwarza różnorodne przepływy obciążenia i prądy zwarciowe, zmieniając przepływy jednokierunkowe na struktury dwukierunkowe i zmieniając charakterystyki prądów zwarciowych. Zaimplementowane tradycyjne metody lokalizacji zwarcia odpowiadają metodzie fali biegnącej i metodzie impedancyjnej. Dyrekcja Generalna ds. integracji stawia nowe wyzwania, dlatego konieczne jest zaproponowanie lub przyjęcie modeli usprawniających proces lokalizacji. W ciągu ostatnich lat wprowadzono kilka technik sztucznej inteligencji (AI), które dają dobre wyniki ze względu na wysoką wydajność i zdolność do szybkiego reagowania. W niniejszym artykule dokonano przeglądu opartych na sztucznej inteligencji technik lokalizacji uszkodzeń w sieciach dystrybucyjnych z DG. Chociaż postęp jest obiecujący, wiele pytań wciąż wymaga odpowiedzi; stałą pracą jest identyfikacja postępów w sztucznej inteligencji w celu uzyskania lepszych wyników. Dodatkowo wdrażane strategie muszą być skalowalne, aby zmniejszyć obciążenie obliczeniowe i móc rozwiązywać problemy o większej złożoności. (Inteligentne algorytmy lokalizacji uszkodzeń dla sieci dystrybucyjnych generacji rozproszonej: przegląd)

Keywords: intelligent optimization, distributed generation, artificial intelligence, machine learning, fault location.

Słowa kluczowe: lokalizacja uszkodzeń, sieć rozproszona, sztuczna inteligencja

Introduction Energy systems are continuously evolving. They must be designed under adaptive models allowing them to adapt to network operators’ and consumers’ constant changes. In order to overcome the challenges of the new electrical systems, it is necessary to incorporate electronic, electrical, information, and advanced manufacturing technologies, which is a requirement for the new energy business models, in a sector that in its transition seeks to integrate: renewable sources, direct current transport systems, energy storage, metering systems, smart grids and the participation of endusers [1].

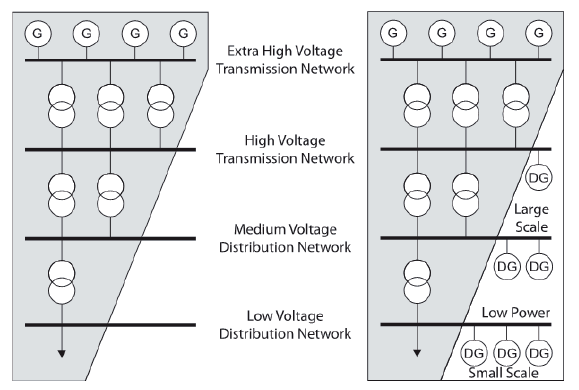

DG represents a “change in the philosophy of electric power generation” that is not new [2], and its implementation allows taking on the challenges of new energy business models. DG has an extensive list of advantages. However, it generates problems on the distribution networks and the transmission system, depending on the own characteristics of the electric power system and the level of penetration [3]. With the connection of generation to the distribution network, part of the system loses its radial system characteristics, modifying: the unidirectional flow, the magnitude, and direction of the short-circuit currents, which causes the incorrect operation of the protection system, failures in the overcurrent schemes and general variation in the operation of the system, affecting the security and reliability in the supply and quality of the energy delivered [4]. DG can be connected at various voltage levels from 120/230 V to 150 kV. As shown in Fig.1, only low power generators can be connected to the lower voltage networks, but large installations of a few hundred megawatts are connected to the busbars of high voltage distribution systems [5].

Many small units integrated into the distribution grid are renewable energy sources, such as wind turbines, small-scale hydroelectric plants, and photovoltaic panels, but high-efficiency non-renewable energy sources, such as small combined heat and power plants, are also implemented. The technologies implemented for DG can be classified according to the resource of generation and type of storage [6], [7]. Distributed Energy Resources (DER) include all forms of electricity generation and storage interconnected to the power system at the medium and low voltage distribution levels [8].

DG integration generates benefits. These benefits include the reduction of line losses, minimization of environmental impacts, increase in efficiency, safety and service provision indicators, reduction of congestion in the transmission and distribution network, and improvement in voltage profiles [5]. However, it also has disadvantages, such as changes in unidirectional flows by bidirectional structures, alteration of fault current characteristics (Fig.2), protection system sensitivity, and network reliability.

The rate of change of fault currents depends on the capacity of the DG incorporated in the system [9]. The protection system adjustment requires the characterization of the performance of the current flows as a function of the type of fault. For example, for three-phase failure in radial systems, the network contribution to the total fault current will be reduced by the DG contribution. Because of this reduction, the short circuit can remain undetected because the grid contribution to the short circuit current never reaches the pickup current of the power relay. Overcurrent relays, directional relays, and reclosers depend on their operation to detect an abnormal current. These problems depend on the protection system applied and, consequently, on the type of distribution network [9], [10]. In general, protection problems can be divided into three categories: Fault detection problems, Fault location problems, Selectivity problems.

In distribution networks with DG penetration, fault location poses a large number of challenges; the traditional methods developed cannot be applied directly due to the variation in short-circuit capacities, the position of the generation systems, bidirectional current flows, the presence of non-homogeneous lines, unbalanced loads, as well as the various branches and laterals [11]. In recent years, several methods have been proposed for fault location in distribution lines. The proposed models have multiple techniques, some deterministic and others probabilistic, and their applications are diverse. However, like many areas of engineering, they are limited by the application system. In the case of fault location, the developed models focus their efforts on solving problems of centralized architectures in transmission and distribution. Therefore, it is necessary to identify and implement fault location strategies that are fast and accurate when incorporating end-user-side generation [12].

This article reviews AI-based techniques for fault location in distribution networks with DG. This article is structured as follows: the first section corresponds to the introduction, the second section presents the review of fault location techniques, which represents the current regulations, the classification of location methods, some background, and a comparative analysis according to the information presented. Finally, in the last section, the general conclusions of the work are presented.

Fault location in distribution networks with DG

The generation at the demand points produces a variation of the load flow and fault currents. Therefore, improving fault diagnosis schemes for this type of architecture is a relevant factor; the early location of a fault accelerates the restoration process, which improves the reliability indicators of the system [13]. In distribution networks, non-homogeneous lines, out-off balance loads, and various branches interfere with the direct application of traditional fault location methods.

Fault location schemes in distribution networks that do not use physical inspection are designed for unidirectional power flows, posing more challenges for networks with DG incorporation [11], Therefore, it is necessary to develop advanced and accurate techniques that adapt to new challenges and permanent changes in distribution networks [14].

On DG fault location, several techniques have been presented in the literature, which is based on modifications of traditional methods: traveling wave methods and impedance methods; additionally, during the last years, a considerable number of knowledge-based techniques have been proposed for fault location. IA is a multidisciplinary area that belongs to the knowledge-based strategies and has presented great results for this type of problem due to its high performance, adaptation, and capacity to provide a fast response during the fault location process. However, it requires a high volume of information for the training and validation tests of the different models, which can generate slow convergence characteristics and high computational load.

In IA for fault location, there is no one technique that is the best, each structure has a considerable number of advantages and disadvantages, but a model that benefits a specific activity or metric and that also fits the current challenges of distribution systems can be proposed. The following is a review of fault location techniques for DG systems, which presents the current regulations, the classification of location methods, some background information, and a comparative analysis according to the provided information.

Standards Fault Location

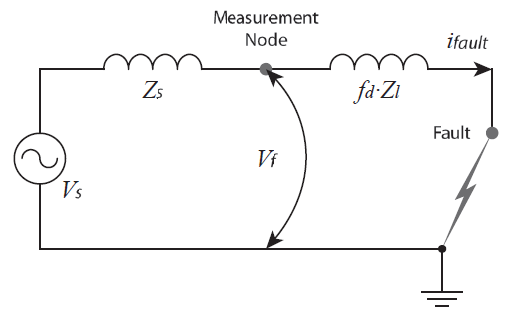

According to the IEEE standard [15], fault location techniques are classified into impedance-based and traveling wave technologies. Impedance-based algorithms use fundamental frequency (60Hz) voltage and current phasors recorded by digital relays, digital fault recorders, and other Intelligent Electronic Devices (IED) during a fault to estimate the apparent impedance between the IED and the short-circuit fault location. Algorithms that estimate the fault distance from measurements at one end of the line are defined as single-ended impedance-based algorithms; those that use measurements at more than one end of a line are called multiple-ended impedance-based algorithms [16], [17]. Fig.3 shows the simple circuit of the impedance based method. The measurement to find the fault distance from the measurement node fd is the value of the impedance per unit line of the distribution system.

The advantage of the impedance-based method is that it is cheaper compared to the traveling wave method, only requiring measurement data from the distribution line. The data must be recorded frequently to monitor the power system. The main disadvantage is the inaccuracy in fault location due to the reconfiguration of the system each time a DG source is disconnected or connected, which generates the method to provide multiple estimates of fault location [18], [19]. Variations of the method, such as the conversion of estimated apparent line reactance to distance and Thevenin’s equivalent method, can be used to calculate fault voltage and current [20].

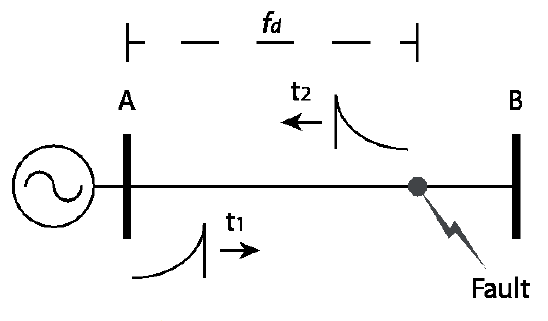

On the other hand, traveling-wave fault location algorithms depart from the system’s operating frequency, using the high-frequency waves generated by the fault to determine the location. Fault location using traveling wave technology (Fig.4), uses the time (t1 and t2) it takes for a wave to travel from the fault point (fd) to the fixed reference point (Node A) where the measurement is taken [15]. The method records the nodes from where the wave is transmitted and where it is reflected. In order to identify the fault location, it is necessary to measure the sum of the fault wave traveling time reflected at the recording node. The advantage of this method is that the load variation, series capacitor bank, and high resistance to the ground do not affect the location technique. Subsequent to the impedance method, traveling wave fault location techniques can also be classified into single-ended (Fig.4) and two-ended algorithms. The disadvantage of this method is that the equipment and devices used in the procedure are high-priced, such as GPS and transient waveform capture sensors.

Several fault location algorithms have been developed in the traveling wave and impedance-based categories. Most of these algorithms aim for the same goal, which is to locate the fault with the highest accuracy. Each study makes different assumptions and uses a data variety to achieve this result. What is the best fault location algorithm? Unfortunately, there is no one-size-fits-all answer. The correct answer is that it depends. It depends on the data available for fault location, the system to which the algorithm will be applied, and the characteristics of the fault [16].

IA Techniques for DG System Troubleshooting

With the accelerated development of distribution networks, users have demanded higher reliability and quality of service delivery. Statistical data show that most power grid failures occur in the distribution network, and 80% of distribution network failures are line failures [21].

Fault location in distribution lines is the first step to maintaining the safety and operation of the system [22]. After a disturbance occurs, the protection scheme must detect and locate the fault to isolate the area. The response must be fast and accurate to avoid damage to the equipment and prevent the failure from spreading to the entire system [10], [19].

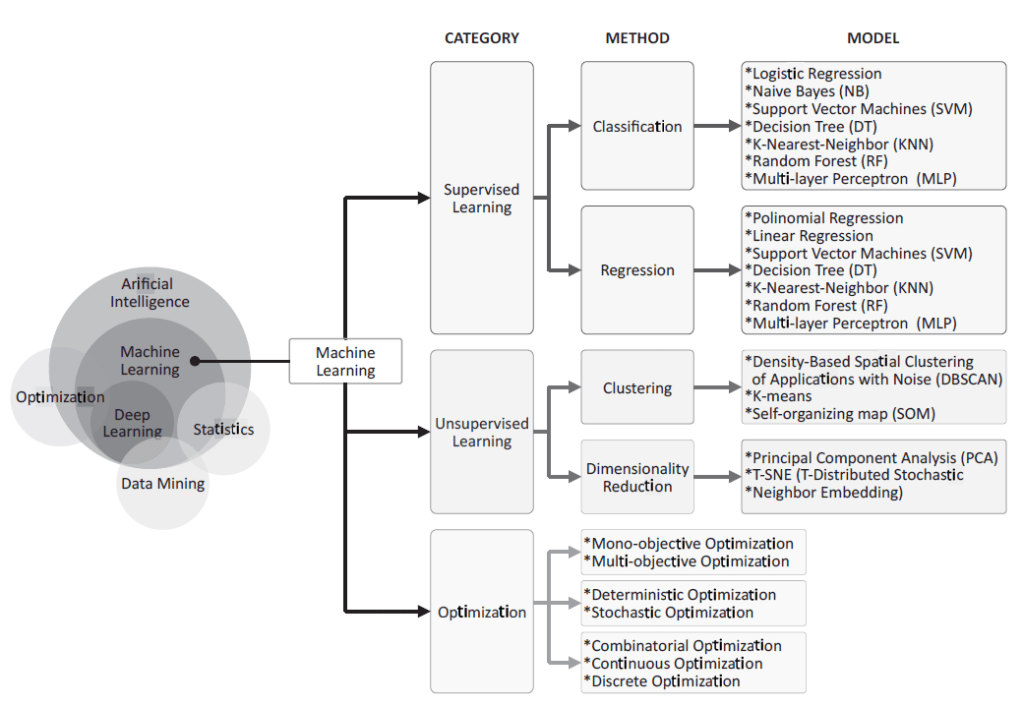

Protection schemes prefer to disconnect DG sources upon a fault or any other disturbance to ensure there is no contribution to the fault current. However, the practice of removing DG is not reliable. Moreover, non-selective removal of DG is neither recommended nor acceptable in a multi-service power supply market [23]–[25]. During the last few years, several methods have been proposed for fault location in systems integrating DG; Fig.5 shows the classification of the methods according to traditional and intelligent system-based strategies.

It is relevant to identify and localize the fault diagnosis in distribution networks. In order to fulfill the demand, more advanced and accurate techniques are required to adapt to the new challenges of the distribution system, such as the incorporation of DG and the increased participation of DER. Because of the structure, wide applications, and excellent results obtained in different engineering areas, knowledge-based methods correspond to computer science that can solve the new challenges in fault location.

Knowledge-based methods

IA, a multidisciplinary area that combines branches of science such as logic, computer science, and philosophy, is concerned with designing and creating artificial entities capable of solving problems using human behavioral algorithms. A significant number of AI-based techniques have been proposed in the literature for power system analysis. However, there is no single algorithm that solves better a general problem. IA is oriented according to the problem to be solved. A proposed hierarchical organization of learning algorithms and their dependency is shown in Figure 6 [26], [27].

Learning machines are a subfield of AI and computer science; they have evolved from pattern recognition to analyzing the structure of data and fitting it into models that users can understand and replicate. This advance is considered the starting point for the development of data-driven services in the power sector. Figure 7 provides some applications of learning machines in the future of power grids.

For fault location using AI, the most commonly used techniques implement neural networks, support vector machines, fuzzy logic, genetic algorithms, and the matching approach. However, some methodologies are available in the literature, some new ones arising from authors’ proposals for specific applications, and others based on hybrid models. These proposals use the “No-Free-Lunch” principle [28], characterize the advantages and disadvantages of two or more strategies, and then combine them in such a way that the overall algorithm is better than the individual ones [29], [30].

In the field of optimization, there have been numerous studies focusing on the design of the algorithms for specific problems considering different backgrounds and objectives. According to the research approaches, the principal studies on intelligent optimization algorithms can be divided into separate groups. Fig.8 presents a proposal for the taxonomy of intelligent optimization algorithm [31].

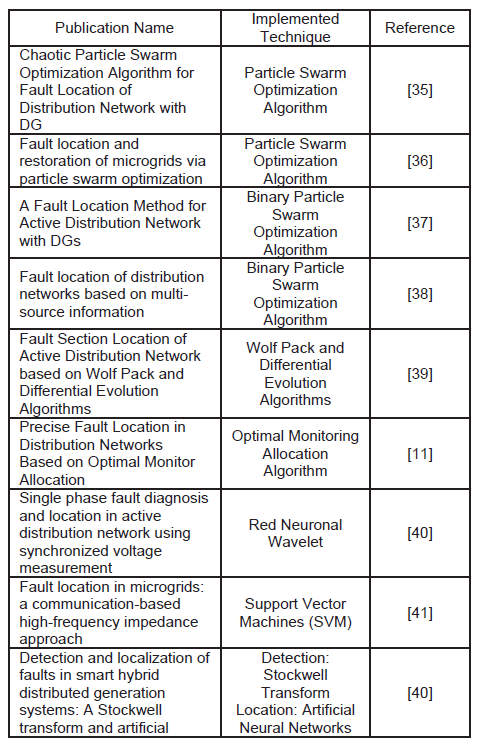

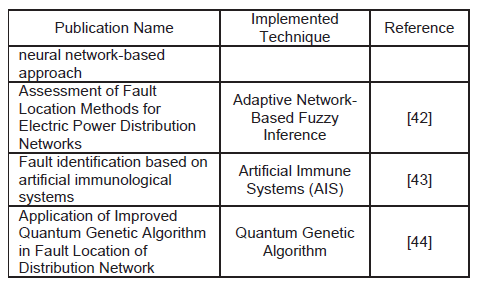

Table 1 presents some examples of knowledge-based techniques for fault location in distribution lines with DG.

Table 1. Example of knowledge-based techniques

According to the “No-Free-Lunch” theorem, no single technique is best. Each technique structure has some advantages and disadvantages, allowing them to be characterized for specific problems. Fault localization using IA methods generates new challenges because it requires training and validation data, along with robust processing equipment [45], [46]. The main challenges regarding the possible implementation of intelligent techniques for fault localization are:

• The quality and selection of information for model training and validation.

• Limited or inaccurate training and validation information.

• Slow convergence in the training process according to the criteria of the model to be implemented.

• Retraining every time there are changes in the system state.

• High computational load.

• Not only must they deliver good results and solve complex tasks, but they must also be designed to be efficient.

Background Analysis

The background is analyzed from three approaches, fault location in distribution lines, IA and optimization techniques for fault location in distribution networks, and IA techniques for fault analysis in DG. Relevant research relating to some of the described approaches was identified. The review starts with a general description of the publications and then specifies each one of them from their objectives, methodology, results, and simulation tool used.

In the field of fault location in distribution lines, three publications and the IEEE standard are described. It is essential to present as background the standard C37.114- 2014 – IEEE [15], a guide for determining fault location in alternating current transmission and distribution lines. This paper presents the description of traditional approaches and measurement techniques used in modern devices for fault location: single and two-terminal impedance-based methods and the traveling wave method.

Regarding the different studies in this field during the last few years, several methodologies describe techniques, such as Wavelet transforms, monitoring systems, and others. In addition, proposals are made to improve the model based on traveling waves. [47] propose an adaptive protection scheme for the localization of single-phase faults using traveling waves, and [48] analyze the localization of high impedance faults through the communication system. The results obtained in each of the studies allow identifying that the strategies selected for the adjustment of the respective models have good performances. However, they do not present comparative analysis with other types of strategies, [48] analyzing the feasibility of implementing the strategy for smart grids. Regardless, they do not quantitatively validate the statement. [49] use the Stockwell transform to obtain a classifier. Nevertheless, although the analysis performed can be extrapolated to fault location, the results presented are focused on fault classification. In general, the three papers presented use radial case studies; the models are not evaluated for bidirectional stream flows.

Below are described the two publications cited for the distribution line fault location.

Authors in [48] analyze the faults that do not touch the ground, highlighting the shortcomings of the current location systems to characterize this type of disturbances. The location of high impedance faults in distribution systems is currently little analyzed; the problem lies in the fact that the identification systems use as criteria the increase of the current magnitude, a high impedance fault does not cause a considerable change in the current flow. Therefore, it is not easily detectable. The solution to identify and locate these faults corresponds to visual diagnosis by the maintenance service or by the users. In order to identify and characterize these faults in the networks, the authors propose a model based on the “Frequency Power Line Carrier Communication Guardian.” The implemented technique is a radial circuit with a feeder, a distribution line, and a monitoring system. This circuit also includes two measurement transformers, four switches, a coupling capacitor, and a programmable logic controller into the system. MATLAB and PSCAD are used as simulation tools.

Authors in [47] analyze the overcurrent protection schemes for shunt faults in distribution systems, specifically, evaluate the disadvantages of traveling waves for the single-phase faults analysis. The authors develop an adaptive model of the traveling wave technique, which allows the proposed model to accurately identify the singlephase ground fault from other short-circuit failures. The implemented system is a radial circuit with two nodes and a distribution line. The simulation is performed through a protection scheme for the overcurrent function.

Authors in [49] globally analyze the use of signal processing and techniques for fault identification in distribution lines. The authors present a short description based on bibliographic references on the Wavelet Transform (WT), the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT), the Hilbert Huang Transform (HHT), and the Gabor Transform (GT). Specifically, the authors propose an algorithm that decomposes the voltage and current signal through the Stockwell Transform; from this decomposition, they obtain the S matrix and use the mean values of the matrix as the fault index. The study was carried out in MATLAB using the IEEE-13 bus test system.

In the area of AI and optimization techniques for fault location in distribution networks, three publications work together with the two approaches and are related to the present research proposal are described. Additionally, [50] implement the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT). The authors implement six AI strategies, Bayes, multilayer neural networks, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS), and support vector machine (SVM) as classification techniques. [51] implement wavelet transform and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS) to locate transient fault zones. And, [52] implement artificial neural networks backpropagation for overhead line fault location.

Besides, [50], uses statistical analysis to compare different classification strategies establishing advantages and disadvantages of the models implemented. [51] and [52] do not present discussions on other possible IA techniques, nor do they include proposals for the bidirectional current systems analysis. Several IA and optimization techniques can provide efficient results to the fault location process. In the same way, [50] incorporate statistical metrics while [51] include performance metrics based on computational load and execution times, which are relevant characteristics for this type of strategy. However, in the fault analysis area, this metric is rarely studied, as identified in [52], where the model performance is analyzed but not its response time; the objective is to locate the fault in the shortest possible time.

Below are described the three publications cited for the area of IA and optimization techniques for fault location.

Authors in [50] implement the Discrete Wavelet Transform (DWT) for the analysis of fault current signals that are obtained through simulations in MATLAB, as classification techniques; they perform a comparative analysis of six strategies of AI, Bayes, multilayer neural networks, adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference systems (ANFIS) and support vector machine (SVM). Average absolute error, root average square error, kappa statistic, success rate, and discrimination rate are used to compare the strategies. The results show that the ANFIS and SVM classifiers are the most effective ones, and their performance is substantially superior to other classifiers. The simulations and design of the classifiers are performed in MATLAB, which implements a radial distribution system.

Authors in [51] develop a method to locate the transient fault zone and classify the fault type in power distribution systems using the wavelet transform and adaptive neurofuzzy inference systems (ANFIS). The study highlights the challenges, costs, and low accuracy of the recent fault location techniques in distribution lines. The strategy presented by the authors extracts current signals from the main feeder, and through ANFIS networks, four algorithms are implemented to locate the fault zone, one algorithm for each branch fault. The model has lower complexity than traditional methods; this criterion is established by the computational load and execution time decrease. Additionally, this method represents a higher accuracy; the maximum error observed was less than 2 %. The simulations are performed in EMTP-RV for a 25 kV radial distribution system.

Authors in [52] describe a fault location algorithm for overhead power distribution lines based on an artificial neural network. In general, techniques based on neural networks perform better in the presence of fault resistance, power system parameter variations and do not require accurate knowledge of the configuration of the power system configuration. Artificial neural network feedforward with backpropagation algorithm with a Levenberg- Marquardt training function is used. The inputs to the neural network are trained through the use of frequency information of fault data that were obtained with digital filtering. The algorithm is tested widely for various system conditions according to the type of fault generated in the overhead distribution system that has been modeled with MATLAB software.

AI techniques for failure analysis in DG studies work with both approaches. [53] implement neural networks, [53] support vector machines, and [54] support vector machines, and [55] metaheuristic optimization.

The results presented in [53], [54], [55] allow us to identify the performance of the selected techniques; good results and relevant metrics are presented for the type of problem analyzed. However, some techniques have been proposed in the literature in recent years, and as identified in the papers cited below, there is no single best algorithm for a general problem. If an algorithm outperforms others in some function, there will be some tasks in which other algorithms will be more efficient. A possible strategy to improve performance is to propose algorithms based on hybrid structures; this allows characterizing the advantages and disadvantages of two or more approaches and then combining them so that the overall algorithm is better than the individual ones.

Below are described the three publications that work on DG fault location approaches.

Authors in [53] propose a system based on electrical synaptic transmission for locating faults in distribution lines with DG for the bidirectional current flow analysis. The bidirectional electrical synaptic transmission characteristics are related to the direction of the current in a distribution system by the incorporation of generation at the demand points. In order to verify the accuracy of the method in this research, three types of faults are analyzed, single faults, multiple faults, and misinformation faults. Additionally, the efficiency of the model is compared as a function of the complexity of the distribution network. Finally, the strategy, methodology, and metrics implemented demonstrate that the model has efficient results. The models are analyzed through matrix structures, using MATLAB as a simulation tool.

Authors in [54] propose an augmented current tracing algorithm with a support vector machine. The objective of the tracing algorithm is to construct a trace of the flow and direction of currents from connected sources at different nodes of the distribution system. The support vector machine is trained as a classification technique to identify the traced fault streams. The plotting and classification are compared with the original circuit equivalents. For the support vector machine, it was evaluated and compared using different kernel methods, improving the sensitivity to very low-level faults. In general, the proposed procedure represented efficient results, with good fits for the overcurrent protection scheme on the primary side of the distribution network. The simulation tool is not specified.

Authors [55] analyze fault location for the improvement and safety of DC distribution networks. For this type of system, when a line fails, the capacitor of the conversion system discharges rapidly, causing the fault current to increase in a short time, which is extremely detrimental to the safety of the system. So, it is required that the fault is located in the shortest possible time. DC networks are the most promising power distribution method for new loads being connected to the system, such as electric cars, smart buildings, and data communication. The authors highlight that there is little research on fault identification and location methods. A particle swarm algorithm is proposed for parameter identification. The objective is to optimize the measurement results to decrease the errors caused by inaccurate sampling. The results show that the method is not affected by transition resistance; and, the positioning accuracy is high. The fault location method is verified in the MATLAB simulation platform.

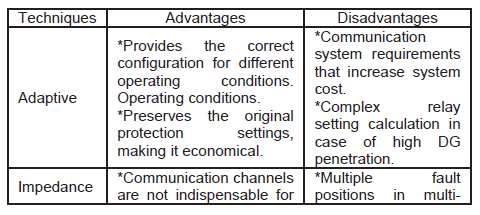

Comparative Analysis

Table 2 displays a comparative analysis of the previously mentioned fault location methods for distribution systems integrating DG.

Table 2. Comparative analysis of fault location methods integrating DG [24]

Conclusions

In order to overcome the challenges of new electrical systems, it is necessary to incorporate advanced computational strategies. During the last few years, several techniques have been presented for fault location in distribution lines with DG, where IA has presented great results due to its high performance and capacity to provide a fast response during a fault. From these reviews, it is evident that there is no optimal solution to the problem of fault location in distribution lines with DG. Because of the generality of IA, it is not possible to characterize an algorithm as the best strategy for fault location. Although the advances are promising, many questions still need to be answered. The ongoing work is to identify the advances in IA to obtain better results. Additionally, the strategies implemented must be scalable to ease the computational load and be able to solve problems of higher complexity.

REFERENCES

[1] U. del V. Ministerio de Minas y Energía, Universidad Nacional de Colombia, UPME, Observatorio Colombiano de Energía. Aproximación a las condiciones para su conformación. 2018.

[2] R. Naghizadeh, H. Afrakhte, and M. Ziapour, “Smart Distribution Network Reconfiguration Based on Optimal Planning of Distributed Generation Resources Using Teaching Learning Based Algorithm to Reduce Generation Costs, Losses and Improve Reliability,” in Electrical Engineering (ICEE), Iranian Conference on, 2018, pp. 1125–1131, doi: 10.1109/ICEE.2018.8472451.

[3] M. B. de las Casas, H. R. Quintero, I. O. Sosa, D. S. Morales, and L. E. L. Mendoza, “Influencia de la generación distribuida en los niveles de cortocircuito y en las protecciones eléctricas

subestaciones de 110/34, 5 kV,” Ing. Energética, vol. 30, no.1, pp. 3-a, 2009.

[4] T. C. Srinivasa Rao, S. S. Tulasi Ram, and J. B. V. Subrahmanyam, “Fault Signal Recognition in Power Distribution System using Deep Belief Network,” J. Intell. Syst., vol. 29, no. 1, pp. 459–474, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1515/jisys-2017-0499.

[5] N. Jenkins, J. . Ekanayake, and G. Strbac, Distributed Generation. India, 2014.

[6] T. Adefarati and R. C. Bansal, “Integration of renewable distributed generators into the distribution system: a review,” IET Renew. Power Gener., vol. 10, no. 7, pp. 873–884, 2016.

[7] C. L. Trujillo et al., Microrredes eléctricas, Primera Ed. Bogotá, 2015.

[8] L. Strezoski, I. Stefani, and B. Brbaklic, “Active Management of Distribution Systems with High Penetration of Distributed Energy Resources,” in IEEE EUROCON 2019 -18th International Conference on Smart Technologies, 2019, pp. 1–5, doi: 10.1109/EUROCON.2019.8861748.

[9] D. Gaonkar, Distributed generation. Croatia: BoD–Books on Demand, 2010.

[10] X. Chen and Z. Jiao, “Accurate Fault Location Method of Distribution Network with Limited Number of PMUs,” in 2018 China International Conference on Electricity Distribution (CICED), 2018, pp. 1503–1507, doi: 10.1109/CICED.2018.8592074.

[11] H. Sun, H. Yi, F. Zhuo, X. Du, and G. Yang, “Precise Fault Location in Distribution Networks Based on Optimal Monitor Allocation,” IEEE Trans. Power Deliv., vol. 35, no. 4, pp. 1788–1799, 2020, doi: 10.1109/TPWRD.2019.2954460.

[12] S. F. Alwash, V. K. Ramachandaramurthy, and N. Mithulananthan, “Fault-Location Scheme for Power Distribution System with Distributed Generation,” IEEE Trans. Power Deliv., vol. 30, no. 3, pp. 1187–1195, 2015, doi: 10.1109/TPWRD.2014.2372045.

[13] A. Tashakkori, P. J. Wolfs, S. Islam, and A. Abu-Siada, “Fault Location on Radial Distribution Networks via Distributed Synchronized Traveling Wave Detectors,” IEEE Trans. Power Deliv., vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 1553–1562, 2020, doi: 10.1109/TPWRD.2019.2948174.

[14] S. Seghir and T. Bouthiba, “Impedance correction method of distance relay on high voltage transmission line,” Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, vol. 97, 2021.

[15] IEEE, “Guide for Determining Fault Location on AC Transmission and Distribution Lines,” C37.114-2014. pp. 1–76, 2015, doi: 10.1109/IEEESTD.2015.7024095.

[16] S. Das, S. Santoso, and S. N. Ananthan, Fault Location on Transmission and Distribution Lines: Principles and Applications. John Wiley & Sons, 2021.

[17] J. Herlender, J. Iżykowski, and E. Rosołowski, “Impedancedifferential relay as a transmission line fault locator,” Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, vol. 93, 2017.

[18] S. Dadary and H. Afrakhte, “Accuracy improvement of impedance-based fault locating method in distribution systems with DGs considering loss of laterals and load variations,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 27, no. 11, p. e2420, Nov. 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/etep.2420.

[19] H. H. Goh et al., “Fault location techniques in electrical power system: A review,” Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci., vol. 8, no. 1, pp. 206–212, 2017.

[20] International Electrotechnical Commission, “IEC 60909 – Shortcircuit currents in three-phase,” vol. 0. 2016.

[21] B. Zhang, H. Liu, J. Song, and J. Zhang, “Simulation on Grounding Fault Location of Distribution Network Based on Regional Parameters,” in 2019 IEEE 19th International Symposium on High Assurance Systems Engineering (HASE), 2019, pp. 216–221, doi: 10.1109/HASE.2019.00040.

[22] B. Jiang, X. Dong, S. Shi, and B. Wang, “Fault line identification of Single Line to Ground fault for non-effectively grounded distribution networks with double-circuit lines,” in IEEE Power and Energy Society General Meeting, Jul. 2015, vol. 2015- Septe, no. 51120175001, pp. 1–5, doi: 10.1109/PESGM.2015.7286346.

[23] A. Bahmanyar, S. Jamali, A. Estebsari, and E. Bompard, “A comparison framework for distribution system outage and fault location methods,” Electr. Power Syst. Res., vol. 145, pp. 19– 34, 2017, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2016.12.018.

[24] R. Kumar and D. Saxena, “A Literature Review on Methodologies of Fault Location in the Distribution System with Distributed Generation,” Energy Technol., vol. 8, no. 3, p. 1901093, Mar. 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1002/ente.201901093.

[25] N. Gana, N. F. Ab Aziz, Z. Ali, H. Hashim, and B. Yunus, “A comprehensive review of fault location methods for distribution power system,” Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci., vol. 6, no. 1, 2017, doi: http://doi.org/10.11591/ijeecs.v6.i1.pp185-192.

[26] K. S. M. H. Ibrahim, Y. F. Huang, A. N. Ahmed, C. H. Koo, and A. El-Shafie, “A review of the hybrid artificial intelligence and optimization modelling of hydrological streamflow forecasting,” Alexandria Eng. J., 2021.

[27] S. Barja-Martinez, M. Aragüés-Peñalba, Í. Munné-Collado, P. Lloret-Gallego, E. Bullich-Massagué, and R. Villafafila-Robles, “Artificial intelligence techniques for enabling Big Data services in distribution networks: A review,” Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev., vol. 150, p. 111459, 2021, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rser.2021.111459.

[28] D. H. Wolpert and W. G. Macready, “No free lunch theorems for optimization,” IEEE Trans. Evol. Comput., vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 67–82, 1997, doi: 10.1109/4235.585893.

[29] Y. Shi, Y. E. Sagduyu, T. Erpek, K. Davaslioglu, Z. Lu, and J. H. Li, “Adversarial Deep Learning for Cognitive Radio Security: Jamming Attack and Defense Strategies,” in 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications Workshops (ICC Workshops), 2018, pp. 1–6, doi: 10.1109/ICCW.2018.8403655.

[30] C. Hernández, D. Giral, and H. Marquez, “Evolutive Algorithm for Spectral Handoff Prediction in Cognitive Wireless Networks,” HIKARI Ltd, vol. 10, no. 14, pp. 673–689, 2017, doi: 10.12988/ces.2017.7766.

[31] M. Bkassiny, Y. Li, and S. K. Jayaweera, “A Survey on Machine-Learning Techniques in Cognitive Radios,” IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutorials, vol. 15, no. 3, pp. 1136–1159, 2013, doi: 10.1109/SURV.2012.100412.00017.

[32] M. S. Ibrahim, W. Dong, and Q. Yang, “Machine learning driven smart electric power systems: Current trends and new perspectives,” Appl. Energy, vol. 272, p. 115237, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.apenergy.2020.115237.

[33] A. Sharifzadeh, M. T. Ameli, and S. Azad, “Power System Challenges and Issues,” in Application of Machine Learning and Deep Learning Methods to Power System Problems, Springer, 2021, pp. 1–17.

[34] F. Tao, L. Zhang, and Y. Laili, Configurable intelligent optimization algorithm. Springer, 2016.

[35] K.-C. Chang, R. Zhang, H. Deng, F.-H. Chang, H.-C. Wang, and G. D. K. Amesimenu, “Chaotic Particle Swarm Optimization Algorithm for Fault Location of Distribution Network with DG BT,” in International Conference on Advanced Intelligent Systems and Informatics, 2022, pp. 256–266.

[36] W.-C. Lin, W.-T. Huang, K.-C. Yao, H.-T. Chen, and C.-C. Ma, “Fault Location and Restoration of Microgrids via Particle Swarm Optimization,” Applied Sciences , vol. 11, no. 15. 2021, doi: 10.3390/app11157036.

[37] W. Bao, Q. Fang, P. Wang, W. Yan, and P. Pan, “A Fault Location Method for Active Distribution Network with DGs,” in International Conference on Smart Grid and Electrical Automation (ICSGEA), 2021, pp. 6–10, doi: 10.1109/ICSGEA53208.2021.00010.

[38] W. Li, J. Su, X. Wang, J. Li, and Q. Ai, “Fault location of distribution networks based on multi-source information,” Glob. Energy Interconnect., vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 76–84, 2020, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloei.2020.03.005.

[39] H. Yang, Y. Guo, and X. Liu, “Fault Section Location of Active

Network based on Wolf Pack and Differential Evolution Algorithms.,” Int. J. Performability Eng., vol. 16, no. 1, 2020.

[40] H. Lala, S. Karmakar, and S. Ganguly, “Detection and localization of faults in smart hybrid distributed generation systems: A Stockwell transform and artificial neural networkbased approach,” Int. Trans. Electr. Energy Syst., vol. 29, no.2, p. e2725, Feb. 2019, doi: 10.1002/etep.2725.

[41] S. Beheshtaein, R. Cuzner, M. Savaghebi, S. Golestan, and J. M. Guerrero, “Fault location in microgrids: a communicationbased high-frequency impedance approach,” IET Gener. Transm. Distrib., vol. 13, no. 8, SI, pp. 1229–1237, 2019, doi: 10.1049/iet-gtd.2018.5166.

[42] S. K. Yellagoud and P. R. Talluri, “Assessment of Fault Location Methods for Electric Power Distribution Networks,” in 2018 4th International Conference for Convergence in Technology (I2CT), 2018, pp. 1–8, doi: 10.1109/I2CT42659.2018.9058148.

[43] D. Sonoda, A. C. Z. de Souza, and P. M. da Silveira, “Fault identification based on artificial immunological systems,” Electr. Power Syst. Res., vol. 156, pp. 24–34, 2018, doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.epsr.2017.11.012.

[44] X. Wang, X. Yu, Y. Xue, Y. Zhu, and J. Fu, “Application of Improved Quantum Genetic Algorithm in Fault Location of Distribution Network,” in Proceedings of 2018 IEEE 3rd advanced information technology, electronic and automation control conference (IAEAC 2018), 2018, pp. 2524–2529.

[45] H. M. M. Maruf, F. Müller, M. S. Hassan, and B. Chowdhury, “Locating Faults in Distribution Systems in the Presence of Distributed Generation using Machine Learning Techniques,” in 2018 9th IEEE International Symposium on Power Electronics for Distributed Generation Systems (PEDG), 2018, pp. 1–6, doi: 10.1109/PEDG.2018.8447728.

[46] C. Darab, R. Tarnovan, A. Turcu, and C. Martineac, “Artificial Intelligence Techniques for Fault Location and Detection in Distributed Generation Power Systems,” in 2019 8th International Conference on Modern Power Systems (MPS), 2019, pp. 1–4, doi: 10.1109/MPS.2019.8759662.

[47] X. He, Q. Qian, Y. Wang, Y. Wang, and S. Shi, “Adaptive traveling waves based protection of distribution lines,” in 2018 2nd IEEE Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), 2018, pp. 1–5, doi: 10.1109/EI2.2018.8582627.

[48] B. Nuthalapati and U. K. Sinha, “Fault Detection and Location of Broken Power Line Not Touching the Ground,” Int. J. Emerg. Electr. Power Syst., vol. 20, no. 3, pp. 2–11, Jul. 2019, doi: 10.1515/ijeeps-2018-0321.

[49] R. Sharma, O. P. Mahela, and S. Agarwal, “Detection of Power System Faults in Distribution System Using Stockwell Transform,” in 2018 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), 2018, pp. 1–5, doi: 10.1109/SCEECS.2018.8546879.

[50] V. Veerasamy et al., “High-impedance fault detection in medium-voltage distribution network using computational intelligence-based classifiers,” Neural Comput. Appl., vol. 31, no. 12, pp. 9127–9143, Dec. 2019, doi: 10.1007/s00521-019-04445-w.

[51] A. Khaleghi, M. Oukati Sadegh, M. Ghazizadeh-Ahsaee, and A. Mehdipour Rabori, “Transient fault area location and fault classification for distribution systems based on wavelet transform and adaptive neuro-fuzzy inference system (ANFIS),” Adv. Electr. Electron. Eng., vol. 16, no. 2, pp. 155–166, Jun. 2018, doi: 10.15598/aeee.v16i2.2563.

[52] Y. Aslan and Y. E. Yağan, “ANN based fault location for medium voltage distribution lines with remote-end source,” in 2016 International Symposium on Fundamentals of Electrical Engineering (ISFEE), 2016, pp. 1–5, doi: 10.1109/ISFEE.2016.7803203.

[53] Z. Sun, Q. Wang, and Z. Wei, “Fault location of distribution network with distributed generations using electrical synaptic transmission-based spiking neural P systems,” Int. J. Parallel, Emergent Distrib. Syst., vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–17, Oct. 2019, doi: 10.1080/17445760.2019.1682145.

[54] W. Fei and P. Moses, “Fault current tracing and identification via machine learning considering distributed energy resources in distribution networks,” Energies, vol. 12, no. 22, p. 4333, Nov. 2019, doi: 10.3390/en12224333.

[55] Y. Hui, X. Yan, Q. Bin, and W. Qi, “Fault Location Method for DC Distribution Network Based on Particle Swarm Optimization,” in 2019 IEEE 2nd International Conference on Electronics Technology (ICET), 2019, pp. 335–338, doi: 10.1109/ELTECH.2019.8839476.

Authors: Diego Armando Giral Ramírez, professor Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia. E-mail: dagiralr@udistrital.edu.co

Cesar Augusto Hernández Suarez, professor Universidad Distrital Francisco José de Caldas, Bogotá, Colombia.

E-mail: cahernandezs@udistrital.edu.co José David Cortes Torres, professor Universidad Industrial de

Santander, Bucaramanga, Colombia. E-mail: jose.cortes@saber.uis.edu.co

Source & Publisher Item Identifier: PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, ISSN 0033-2097, R. 98 NR 7/2022. doi:10.15199/48.2022.07.23