Published by Piotr WOŹNIAK, Politechnika Łódzka, Instytut Systemów Inżynierii Elektrycznej

Abstract. This article presents simulation tests showing the benefits of using an additional energy storage device in the form of a supercapacitor in a hybrid car. An original power flow control system was proposed. The main emphasis was placed on determining the driving characteristics, emissions of harmful substances, fuel consumption and increasing the service life of batteries by limiting rapid changes in the charging and discharging currents and the operating temperature of the cells.

Streszczenie. W artykule przeprowadzono badania symulacyjne pokazujące korzyści płynące z zastosowania dodatkowego zasobnika energii w postaci pakietu superkondensatorów w samochodzie z napędem hybrydowym. W tym celu zaproponowano oryginalny system zarządzania energią. Główny nacisk położono na określenie właściwości jezdnych, emisji szkodliwych substancji, zużycia paliwa oraz wydłużenie okresu użytkowania akumulatorów poprzez ograniczenie gwałtownych zmian prądów ładowania i rozładowania oraz temperatury pracy ogniw. (Wykorzystanie hybrydowych zasobników energii w pojazdach z napędem hybrydowym: projekt strategii zarządzania energią oraz badania porównawcze)

Keywords: hybrid vehicles, supercapacitors, energy management systems.

Słowa kluczowe: pojazdy hybrydowe, superkondensatory, systemy zarządzania energią.

Introduction

Increased fuel prices and high stringent requirements for harmful emissions in recent years have made electric and hybrid vehicles more popular. In the first quarter of 2019, a further increase in interest in cars with alternative power supply was visible in Europe. Sales of electric vehicles (EV) increased by 87.5% compared to the first quarter of 2018, and hybrid vehicles (HEV) by 33%. HEV vehicles accounted for around 4.7% of market share, while EV vehicles around 2%. One way to reduce emissions of harmful substances and to comply with applicable standards “downsizing”, i.e. reducing the capacity of internal combustion engines and the use of a turbine or compressor boost. However, this is not advantageous, because the motor often works in conditions of high overload and adversely affects its durability. A much better solution is to support traditional internal combustion engines with an electric drive, i.e. using a hybrid drive (HEV) or elimination of the internal combustion engine and the use of electric drive (EV). Hybrid cars combine the best features of vehicles with an internal combustion engine and cars with electric drive such as: long range, high power, lower fuel consumption, lower emissions [1]. Batteries used in electric and hybrid vehicles lose their performance over time. This is due to redox reactions occurring, overcharge, changes in internal and external environment parameters. They work well when they are charged/unloaded monotone [2, 3]. If the vehicle suddenly accelerates or brakes, the battery cannot be discharged/charged quickly enough. High battery current, especially when acceleration / deceleration is repetitive (when driving in the city) can have a detrimental effect on electrolyte and shorten battery life [2]. The price of batteries is a large part of the value of the entire car and their replacement is associated with high costs. A large number of charging cycles and use in improper conditions cause their degradation and reduction of capacity. Therefore, it is important to properly control the charging process of the battery pack [4].

Unlike batteries, supercapacitors (ultracapacitors) have a low energy density, which means that they cannot be used as the primary power source. Lithium-ion batteries can store about 20 times higher energy density than supercapacitors. Supercapacitors are also not suitable for long-term energy storage due to the fact that the self-discharge speed of supercapacitors is much higher than for lithium-ion batteries (up to 10-20 percent of charge per day). Although they cannot store as much energy and for as long as lithium-ion batteries of comparable size, their advantage is the ability to charge and discharge in a short time, in some cases the charging time is up to 1000 times shorter than the time of charging a battery with similar capacity.

Supercapacitors therefore have a much higher power density than batteries. That is why they are well suited for applications that require frequent charging and discharging cycles, as well as operation at extreme temperatures. In China, some hybrid buses use supercapacitors to increase acceleration, and in the case of trams, these energy reservoirs allow travel from one stop to another, the charging process takes place at the stops. A hypothetical electric car will be considered to justify the use of supercapacitors. It can move with an average power of about 20 kW, however, during rapid acceleration it requires a peak power several times higher, e.g. 100 kW. Although this power level is only needed for a short time, it means that the vehicle needs additional batteries [5, 6, 7]. Supercapacitors can provide this power required for acceleration, while the battery will provide average power during normal driving, which means that generally the vehicle requires a smaller battery. In the world literature, hybrid power systems using batteries and supercapacitors are mainly used in cars with a serial or parallel hybrid drive and cars with only electric drive (EV) [1, 2], including public utility vehicles.

Technologies used

All tests were carried out using the ADVISOR simulation program, developed at the National Renewable Energy Laboratory (NREL – USA) and operating in the MATLAB environment [8]. This software is widely used for research purposes in many academic centers, e.g. [9, 10, 11, 12, 13].

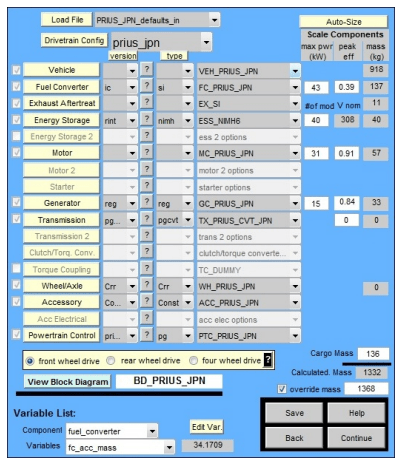

In the main program menu (Fig. 1) it is possible to freely configure the vehicle, for which simulations will be carried out.

As part of the work described in the article, the first-generation Toyota Prius hybrid car model embedded in the ADVISOR program was tested, which entered serial production in 1997. This model and its parameters were adopted as a reference for research consisting in modification of the power supply system aimed at optimizing the use of energy storage in terms of fuel consumption and emissions of harmful substances such as hydrocarbons (HC), carbon oxides (CO), nitrogen oxides (NOx) and solid particles (PM). And also extending the battery life by lowering their operating temperature, charging / discharging cycles and other parameters affecting driving comfort, such as hill climbing ability.

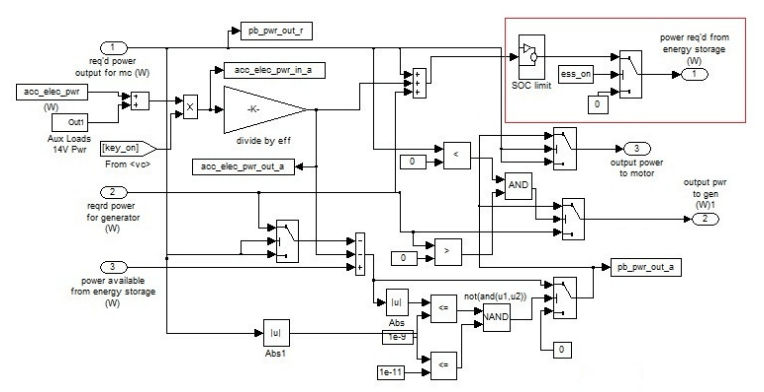

Vehicle parameters and modifications

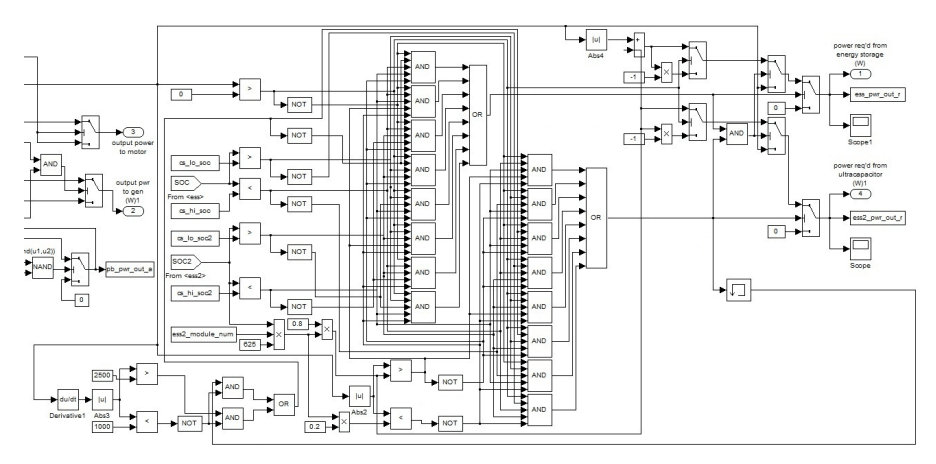

Standard first generation Prius is powered by Ni-MH rechargeable batteries (1.2V cells, 6 cells connected together in a module, 40 modules). The vehicle modification consists in adding an additional energy storage in the form of a supercapacitors package (Maxwell PC2500 – 2700 F 2.5V). The vehicle model includes the mass of the supercapacitors module. The block diagram of the car built in ADVISOR before modification is shown in Fig. 2. Figure 3 shows the power bus model (block ‘prius power bus ‘ in Fig. 2). The block diagram (Fig. 2) and the power bus (Fig. 3) have been modified to add the energy storage. To add a second energy store, the block name and all parameters and variables starting with the prefix ‘ess_’ to ‘ess2_’ have been changed. This was necessary to avoid conflicts with the battery pack model. In the developed strategy for controlling energy storage, the input parameters are: the absolute value of the power for which there is demand at a given moment from energy storage devices (or which is available for energy storage), its sign (a positive value means discharge, and a negative charge, according to the convention adopted in the environment used), restrictions imposed on SOC (state of charge) for both storage tanks and the rate of power change over time (derivative). In addition, the information on which energy storage was previously used is included and restrictions on switching on the battery container are imposed when large instantaneous values of the charging or discharging current are required. This last action is to extend the life of the energy storage, because limiting the on/off cycles also leads to a lower average operating temperature. The possibility of each energy storage unit operation has been taken into account, and with increased power demand at a given moment, as well as in the case of a large amount of recovered power available, simultaneous operation of both tanks is possible, but the preference is always to use the current capabilities of supercapacitors .

To prevent frequent switching between energy storage, two hysteresis loops were used in the control strategy. In the first loop, the current power derivative value and its belonging to the ranges defined by the two values are checked (e.g. 1000, 2500 – these values may be variable, what is more, in practice they can be determined by the driver based on the knowledge of the route, its profile and traffic) and on this basis the preference for energy storage is determined. In the second hysteresis loop, the preference of energy storage is determined depending on the absolute power value in relation to the estimated supercapacitor power. Designed control system (number of inputs 8, outputs 2), including logic after maximum reduction of Boolean expressions has been implemented in Simulink and includes: 31 logic gates (AND, OR, NOT), 10 comparison systems, 6 multipliers, derivative determination block, 2 blocks for absolute value determination and summation system. As a result of its operation, a binary signal is obtained defining the state (on/off) of each energy storage in the next time step. This allows the available/required power to be distributed to energy storage. The fragment marked with a red frame in Fig. 3 has been changed in the power bus. Figure 4 shows the modified part of the power bus. If there is a high demand for power, e.g. rapid acceleration, we use an additional energy storage in the form of a supercapacitor. During calm driving, energy is taken from the main power source.

Simulations

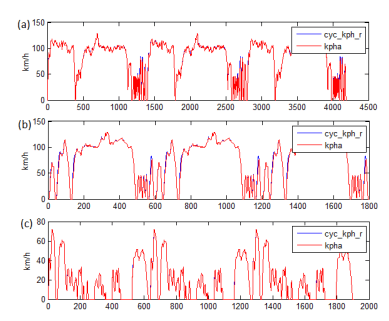

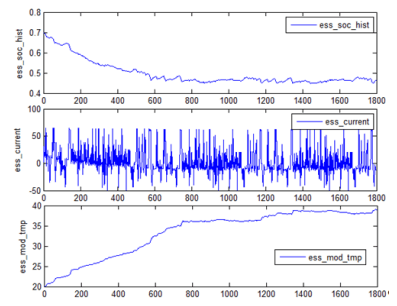

The first simulations were made for two built-in routes (CYC_REP05, CYC_US06) and the route for the agglomeration of Lodz developed by the author (CYC_LODZ). The acquisition of this route was made using parameters read from the vehicle’s OBD interface, and the ride was made during rush hour. Route speed profiles are shown in Fig. 5. To extend the travel time, the cycle was repeated three times. An example of the simulation result in the ADVISOR environment for transit using the built-in Toyota Prius model is shown in Fig. 6. The same initial conditions were used for all tests: SOC=0,7; SOC2=0,7; temp=20°C.

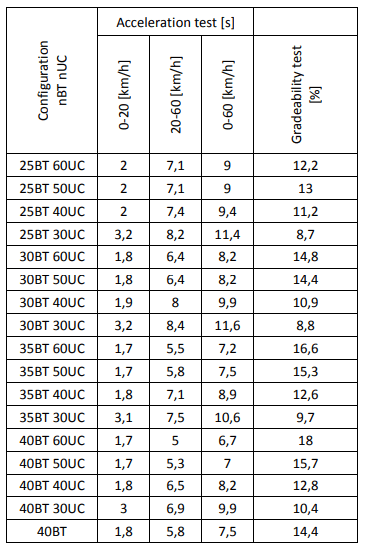

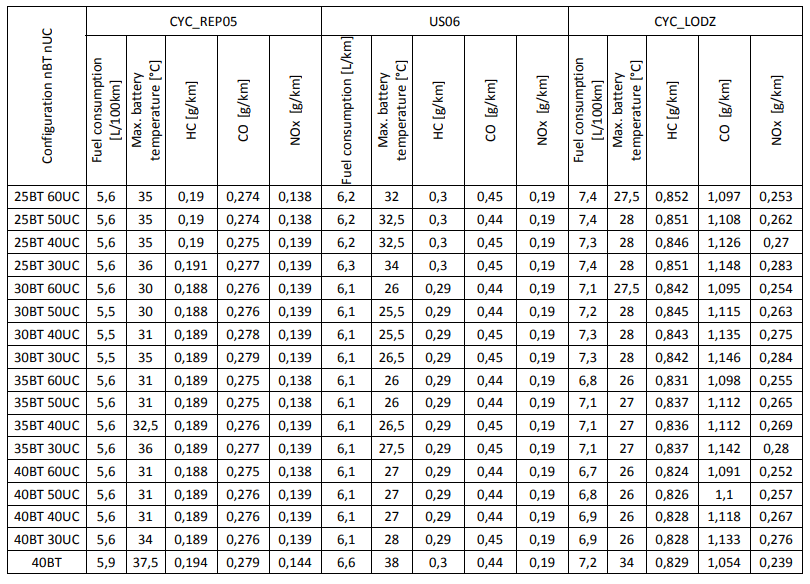

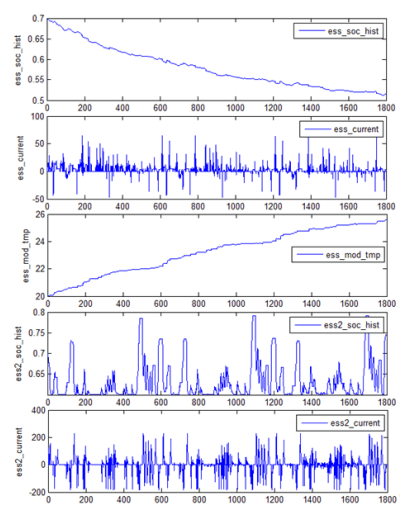

Then a series of simulations was performed using a modified version of the vehicle with an additional energy storage in the form of a supercapacitors package (30-60 modules) using the model embedded in the ADVISOR environment and a modified energy management system as described in chapter 3. An example of the simulation result is shown in Fig. 7. The rest of the simulation results for all routes in different combinations of the number of battery modules and supercapacitors (nBT and nUC where n is the number of modules, BT – baterries, UC – supercapacitors ) are shown in Table 2. 40BT refers to the original Toyota Prius.

Additionally, for each nBT nUC configuration, perform an acceleration test and gradeability test at 50 km/h, at initial values SOC=0,6 and SOC2=0,6. The simulation results are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. The results of the acceleration and gradeability test

Table 2. Simulation results for the route CYC_REP05, CYC_US06 and CYC_LODZ

Conclusions

The simulation results show that the use of an additional energy storage in the form of a supercapacitor brings, in most cases, many benefits. First of all, in many cases lower fuel consumption has been achieved, which reduces the release of harmful substances by the vehicle. In addition, the use of an additional energy storage(supercapacitor) has reduced the number of battery modules (from standard 40 to 30-35). Less batteries means lower replacement costs when old batteries degrade. The proposed energy management strategy has reduced the average operating temperature of the battery pack, average current drawn from the battery, and on and off cycles, which has a positive effect on extending the life cycle of this energy storage. Adding an additional energy storage in the form of supercapacitors is associated with additional costs, but due to longer life and susceptibility to a large number of charging and discharging cycles (up to 1000000) this investment is a one-off with a typical vehicle life. The big advantage of supercapacitors, unlike batteries, is the ability to receive and release large amounts of energy in a short time, which is included in the proposed control strategy.

REFERENCES

[1] Bosch R., Napędy hybrydowe, ogniwa paliwowe i paliwa alternatywne, WKŁ, 2010

[2] Kouchachvili L., Yaici W., Entchev E., Hybrid battery/supercapacitor energy storage system for the electric vehicles, Journal of Power Sources, 374 (2018), 237-248

[3] Jaroszyński L., Akumulatory litowe w pojazdach elektrycznych, Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, 87 (2011), nr.8, 280-283

[4] Czerwiński A., Akumulatory, Baterie, Ogniwa, WŁK, 2005

[5] King A. , Power-hungry Tesla picks up supercapacitor maker, ChemistryWorld, 2019,

https://www.chemistryworld.com/news/power-hungry-teslapicks-up-supercapacitor-maker-/3010215.article

[6] Juda Z., Zastosowanie superkondensatorów w układzie odzysku energii pojazdu z napędem elektrycznym, Czasopismo Techniczne. Mechanika, 105 (2008), z. 6-M, 191-199

[7] Kasprzyk L., Bednarek K., Dobór hybrydowego zasobnika energii do pojazdu elektrycznego, Przegląd Elektrotechniczny, 91 (2015), nr.12, 129-132

[8] http://adv-vehicle-sim.sourceforge.net/

[9] Chen D., et al., ‘Research on Simulation of the Hybrid Electric Vehicle Based on Software ADVISOR, Sensors & Transducers Journal, 171 (2014), 68-77

[10] Gao D. W., Mi C. , Emadi A., Modeling and Simulation of Electric and Hybrid Vehicles, in Proceedings of the IEEE, 95 (2007), 729-745

[11] Rashid M. I. M., Daniyal H., Mohamed D.I, ‘Comparison performance of split plug-in hybrid electric vehicle and hybrid electric vehicle using ADVISOR’, MATEC Web Conf., 90 (2017), https://doi.org/10.1051/matecconf/20179001019

[12] Szumska E, Pawełczyk M., Ocena korzyści zastosowania napędów hybrydowych w pojazdach komunikacji miejskiej, Autobusy: technika, eksploatacja, systemy transportowe, 18 (2017), 1087-1092

[13] Wu Y., Power Distribution System Modeling and Simulation of an Alternative Energy, 2010,

https://etd.ohiolink.edu/!etd.send_file?accession=ohiou1289960977&disposition=inline

Author: mgr inż. Piotr Woźniak, Politechnika Łódzka, Instytut Systemów Inżynierii Elektrycznej, ul. Stefanowskiego 18/22, 90-924 Łódź, E-mail: piotr.wozniak@dokt.p.lodz.pl.

Source & Publisher Item Identifier: PRZEGLĄD ELEKTROTECHNICZNY, ISSN 0033-2097, R. 96 NR 8/2020. doi:10.15199/48.2020.08.12